Curing

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Curing

Definition

The term curing or hardening is used for metallic materials, building materials such as concrete and also for plastics, especially reactive resins, paints and adhesives (see also: adhesive joints – determination of characteristic values).

Curing

Heat treatment (curing) of metals

In metallic materials, the process of curing actually refers to a heat treatment that is used in particular to increase the strength and hardness of alloys. The increase in temperature increases the mobility in the crystal lattice, which promotes the separation of metastable phases that are deposited, for example, at grain boundaries and thus hinder the dislocation movements in the lattice structure. As a result of this heat treatment, which usually consists of solution annealing below the eutectic point, quenching and subsequent exposure or precipitation, a significant increase in the yield point and hardness of metal alloys (e.g. duralumin) can be achieved.

The curing of building materials

The concrete used in the construction industry is a building material consisting mainly of cement, water and gravel or sand. The cement used as the basis for this material is obtained from lime (CaCO3), marl (a mixture of clay, sand, lime or magnesium carbonate) and/or clay (Al2O3) (aluminium silicate), with the result of the burning process being largely determined by the fineness of the grinding.

The curing, also known as setting, of the cement corresponds to a slow chemical-mineralogical reaction of the cement with the added water, whereby this reaction is significantly dependent on the temperature. Cement is therefore a hydraulic binder that only hardens when water is added (hydration). Concrete is thus a mixture of cement and water, as well as aggregates such as sand or gravel that do not participate in the reaction.

Curing of plastics

In thermosetting plastics, especially casting resins or matrix materials for fibre-reinforced plastics (FRP), polymer-based paints and adhesives, or even elastomers, curing refers to an irreversible chemical cross-linking reaction in which the usually liquid starting materials transition to a solid end state. As a result of cross-linking, the macromolecules are linked to form a three-dimensional network, whereby an increase in the degree of cross-linking (proportion of cross-linking points in relation to the volume of the polymer) leads to an improvement in mechanical and thermal properties, such as strength, modulus of elasticity, hardness and toughness. At the same time, the solubility and ductility of the materials are generally reduced.

Curing of elastomers

In elastomers, this process of cross-linking is referred to as vulcanisation of rubber, whereby sulphur-containing compounds, for example, are used as cross-linking agents or network formers. There are basically two types of cross-linking agents, which either have identical reactive groups (homobifunctional cross-linking agents) or varying groups (heterobifunctional cross-linking agents).

Cross-linking state of plastic products

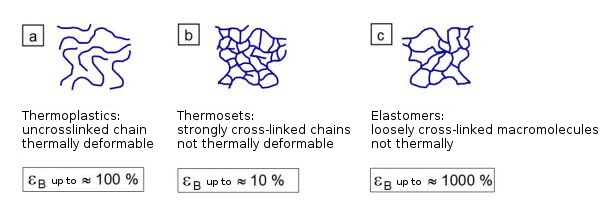

The resulting network density or number of network nodes determines the mechanical (modulus of elasticity, strength and ductility), thermal (flame resistance, glass temperature), thermo-mechanical (heat resistance) and, in some cases, electrical properties (creep current resistance, insulation resistance) of these networked plastic products (Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1: | Cross-linking state and tensile strain at break of a) thermoplastics, b) thermosets and c) elastomers |

Methods for determining the degree of curing

In the field of plastics, fibre-reinforced plastics (FRP) used in lightweight construction in the aerospace industry, the automotive industry and energy technology (wind turbines) are of particular interest. In addition to the actual fibre volume or mass content, the preferred orientation and the laminate structure, the assessment of cavities and other possible defects, such as pores or delamination, as well as the degree of curing of the respective matrix, are of particular importance. The degree of curing of reaction resins can be determined using various test methods, whereby in many cases the chain mobility and the presence of free monomer compounds are assessed using physical measurement principles. Suitable test methods include thermal analysis methods such as differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), dynamic-mechanical analysis (DMA), dynamic mechanical thermal analysis (DMTA) or thermomechanical analysis (TMA), gas chromatography (GC) and dielectrometry, as well as mechanical test methods such as tensile testing, toughness testing or Barcol hardness [1].

Epoxy resins (abbreviation: EP) and unsaturated polyester resins (abbreviation: UP) are the preferred matrix materials for FRP, which is why only these materials will be discussed below. In addition to these two reaction resins, vinyl ester resins (abbreviation: VE), methacrylate resins (abbreviation: MMA), phenol-formaldehyde resins (abbreviation: PF), polyurethane resins (abbreviation: PU) and amino resins, in particular melamine resin (abbreviation: MF and MP) and urea resin (abbreviation: UF).

Effects of the curing process on properties

Epoxy resins are curable reaction resins that are formed by the reaction of the resin and an added hardener, possibly supplemented by additives such as reactive diluents (e.g. monoglycidol ether, polyglycidol ether). This usually exothermic polyaddition reaction produces a thermosetting plastic that is characterised by high strength and chemical resistance, but low ductility and toughness. These properties can be significantly improved by adding inorganic fillers to the resin or by producing laminates or prepregs with glass or carbon fibres. In contrast to UP resin, the stoichiometric ratios between the resin and the hardener must be strictly observed for epoxy resins, as failure to do so will result in either incompletely cross-linked plastics or superfluous monomeric resin or hardener components leading to sticky surfaces or reduced strength of the component. Depending on the type of resin (cold or hot curing), the curing process (cross-linking) can take from a few minutes to several hours, whereby the curing process can take up to several months, especially in the case of thick components or large wall thicknesses or high filler contents. For components with greater wall thicknesses, only low-reactive resin/hardener systems should therefore be used. The processing time of such reaction resins is referred to as pot life and depends largely on the processing temperature, the resin type and the quantity of the mixture. When the pot life is reached, the viscosity of the resin increases in a non-linear function of time until, as a result of the increasing degree of cross-linking, it is no longer possible to process the resin. The pot life of the resin/hardener mixture is significantly influenced by the addition of fillers or reinforcing agents or thixotropic agents such as glass powder or micro hollow glass beads. To shorten the pot life, accelerators can be added to smaller batches, which significantly reduce the reaction time. Epoxy resins can be subjected to heat curing (annealing) after curing to achieve complete cross-linking and higher heat resistance, which can increase the glass temperature TG by up to 30 °C. However, the curing process is also significantly influenced by the type of epoxy resin (bisphenol-based, novolak and special resins) and its chemism.

Unsaturated polyester resins (UP resins) are produced by esterification (polycondensation) of unsaturated and saturated dicarboxylic acids with alcohol as a low-cost alternative to EP resin and as a matrix material for FRP, especially since they are much easier to process than other resins. Normally, the polyester resin forms long, unbranched (linear) molecular chains during curing, but can also form cross-links when styrene is used. UP resin is usually produced from a non-stoichiometric mixture of resin, hardener (MEKP hardener) and accelerator (cobalt as a catalyst), whereby the pot life or processing time can be flexibly adjusted via the amount of hardener or accelerator. The processing temperature is very important for the pot life and should not be lower than 15 °C, as otherwise curing will not be complete and low-molecular components will significantly reduce the mechanical properties of the casting resins or FRP. The resin cures, for example, independently in an exothermic reaction (cold-curing resin) or through the application of heat (hot-curing resin), but sometimes also through UV radiation (stereolithography) or moisture. As a result of this reaction, either a loss of volume occurs due to contraction on all sides, also known as shrinkage, or internal stresses (residual stresses) are generated when contraction is impeded, whereby excessive stress values can lead to blowholes or cracks. Reaction times that are too short usually result in discolouration (yellow to red) of the moulded part and, in extreme cases, can lead to fire in large volumes. In the literature, this effect is often incorrectly referred to as shrinkage, which, in contrast to processing shrinkage, marks a constant change in volume. Over longer periods of use, slight post-shrinkage may occur, caused by the diffusion of solvents or excess hardener components.

As a general rule, fibre-reinforced plastics with a thermosetting matrix cannot be reshaped after curing or cross-linking of the matrix, regardless of the type of resin used [2].

See also

References

| [1] | Höninger, H.: Component Testing. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, pp. 600–624 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [2] | Stoye, D., Freitag, W. (Eds.): Lackharze – Chemie, Eigenschaften und Anwendungen. Carl Hanser, Munich (1996) (ISBN 3-446-17475-3) |