Strength

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Strength

Definition of strength

The term ‘strength’ is frequently used in engineering and in materials and polymer testing as a synonym for maximum or ultimate stress, although it is not explicitly defined even in classic textbooks on technical mechanics [1–3], theoretical mechanics [4] and strength of materials [5, 6].

The reason for this is obviously that this term is only ever valid for the specific application and that a defined stress must be available in this regard. From this perspective, theoretical considerations of stress analysis, e.g. using the shape change hypothesis, are only suitable for describing certain mechanical stress conditions, e.g. using a comparative stress. With increasing complexity of the stress, superimposition of long-term loads with oscillating or impact stresses, these methods are rarely suitable for reproducing reality and predicting an ultimate strength level. If, in addition, superpositions occur due to thermal, chemical and media stresses, and possibly also internal stresses (see: tensile test residual stresses orientation), then these models fail and also reveal the limitations of a universally valid definition of the term ‘strength’.

A universally valid definition of strength could possibly be as follows:

‘Strength is the stress that must be applied to exceed a certain critical stress level, which leads to fracture or irreversible deformation with loss of integrity and functionality of the test specimen, workpiece or component.’

In the case of mechanical stress, as is common in materials or polymer testing, this definition would have to be applied to the specific case and modified as follows:

‘Mechanical strength is a property of a material in response to an applied critical force or moment that must be exerted to cause fracture, cracking or failure or irreversible deformation of a test specimen, workpiece or component with loss of functionality.’

Test methods for determining strength

This definition is applicable to mechanical testing methods and applies equally to uniaxial, biaxial and multiaxial stresses. It can be extended to include mechanical-thermal or mechanical-medial types of stress, for example, using media or temperature chambers, whereby these then represent boundary conditions for the respective mechanical stress.

Mechanical strength can therefore be differentiated according to the type of stress and is then always to be understood as the maximum load (force or moment) in the respective material testing experiment, whereby the following terms are relevant:

- Tensile strength in uniaxial tensile testing,

- Flexural strength in the three-point or four-point bending testing,

- Compression strength in uniaxial compression testing,

- Compressive strength under hydrostatic stress,

- torsional strength in a torsion test,

- shear strength in a single or double shear test,

- buckling strength in a buckling test according to Euler, and

- seal strength in a peel test.

Stress–strain diagrams

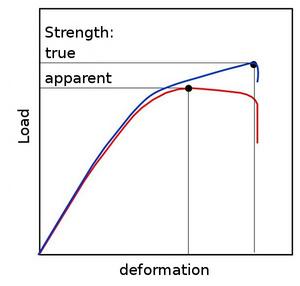

In material or polymer testing, only apparent material values are usually determined, as the measured values are standardised to the geometric initial values. As a result, the ultimate strength can also assume values lower than the respective maximum (fracture strength; see also: fracture) (Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1: | Determination of apparent and true strength in materials testing |

If the actual geometric values are used for standardisation, the true strength is determined at the maximum load (see: tensile test true stress–strain diagram).

However, depending on the type of stress, uni, double and multiaxial tests can form a special category and, depending on the test time, the following strengths and types of tests can be distinguished:

- Quasi-static test methods or short-term tests with the above strengths or the hot strength of metallic materials at elevated temperatures,

- Static long-term tests such as the creep test (creep or relaxation) with time or fatigue strength,

- Vibration tests with, for example, fatigue or continuous vibration strength (see: continuous vibration test) and

- Impact test methods with impact or notch impact strength.

If the strength is standardised in the respective test procedure to the density of the material, the result is the so-called specific strength. Basically, the strength depends on the loading speed (see: test velocity) or the strain rate (impact strength), the temperature (high-temperature strength) and media influences, which is particularly relevant for plastics.

Applications of the term ‘strength’ in other scientific disciplines

As already mentioned, there are other scientific disciplines in which the term strength is used. These include, for example, wear resistance under tribological stress, corrosion resistance under chemical stress, and stress crack resistance (see also: environmental stress cracking resistance) under medial stress. In tests of electrical properties, the term strength is also used for electric breakdown strength, creep current resistance and thermal strength.

In this respect, the definition of strength as resistance to plastic deformation, to the propagation of cracks and to wear is certainly not suitable for even approximately describing the complexity of this term from a materials science perspective.

See also

- Continuous vibration test

- Fracture types

- Flexural strength

- Compression strength

- Shear modulus

- Tensile strength

References

| [1] | Szabó, I.: Einführung in die Technische Mechanik. Springer, Berlin (1984) 8th Edition, (ISBN 3-540-13293-7; see AMK-Library under T 15) |

| [2] | Läpple, V.: Einführung in die Festigkeitslehre. Springer Vieweg Publishing, Wiesbaden (2016) 4th Edition, (ISBN 978-3-658-10610-2; see AMK-Library under T 16) |

| [3] | Göldner, H., Pfefferkorn, W.: Technische Mechanik – Statik, Festigkeitslehre, Dynamik. Fachbuchverlag Leipzig (1990) (ISBN 3-343-00589-4; see AMK-Library under T 18) |

| [4] | Budo, A.: Theoretische Mechanik. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften Berlin (1969) (see AMK-Library under T 19) |

| [5] | Szabó, I.: Höhere Technische Mechanik. Springer, Berlin (1984) 5th Edition, (ISBN 3-540-15007-2) |

| [6] | Issler, L., Ruoß, H., Häfele, P.: Festigkeitslehre – Grundlagen. Springer, Berlin (2006) 2nd Edition, (ISBN 978-3-662-11739-2) |