Crack

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Crack

General definition

A crack is a discontinuity that can be present in a material due to production-related or operational causes [1]. If it exceeds a permissible critical expansion, the crack is the most dangerous of all discontinuities, as it represents a material separation, i.e. a material area whose load-bearing capacity is no longer given due to the destruction of the interatomic bonds. In addition, the interaction of residual stresses and external loads in the vicinity of a crack results in inhomogeneous stress distributions with an extraordinarily high stress concentration. To be on the safe side, most regulations generally treat discontinuities as cracks in fracture mechanics assessments.

Cracks are predominantly areal discontinuities or inhomogeneities. They are labelled as defects if they exceed an impermissible extent.

The term ‘crack’ is not clearly defined in the technical regulations. Generally recognised definitions are:

’A crack is a localised separation of the material structure of small width, but often considerable length and depth‘

’The crack is a limited material separation with a predominantly two-dimensional extension‘

In [2], the crack is characterised as ’a three-dimensional material separation whose three dimensions have a ratio of at least 1 : 10 : 100 to each other" for more precise differentiation from other inhomogeneities such as inclusions, blowholes (see: shrink voids) bubbles or grooves. Accordingly, a defect can be characterised as a crack if its length is more than ten times greater than its depth and this exceeds the gap width by at least a factor of 10.

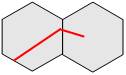

According to Blumenauer [3], one should only speak of a crack in the technical sense when the length or depth of the material separation is about 1 mm. A single crack can generally be sufficiently characterised geometrically for a fracture mechanics assessment by the size of its crack area or the crack length, the crack depth, the crack gap width and the crack inclination. There are surface cracks and internal cracks. In the case of surface cracks, the crack banks (or crack edges), the crack front (in the cross-section of the crack tip) and the crack flanks delimit a crack. In the case of an internal crack, which consists only of the crack front and the crack flanks, the distance to the surface (crack cover) also plays an important role. For a fracture mechanics assessment, it is also crucial whether it is a single crack or multiple cracks. It is important to note whether the cracks are collinear or parallel cracks or entire crack networks.

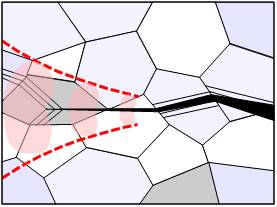

Both cracks and notches are characterised by discontinuities in which surfaces come very close to each other over large areas and which have a linear boundary (crack edge, crack front, notch base) with a very small radius of curvature at least at one point. The surfaces of notches and cracks are very large compared to the volumes that enclose them. As cracks grow, the volume hardly changes, while the crack surfaces continue to increase (see also: notch insertion).

Notches and cracks differ in that the inner boundary surfaces of a crack touch each other in the unloaded state, whereas this is not the case with a notch. From a mathematical point of view, the crack is a discontinuity surface for displacements in the undeformed body that is limited by the crack contour. In mathematical modelling [4], a cut across the largest surface expansion results in a line for the crack and an ellipse for the notch. This means that a crack has an infinitely large curvature at its ends, whereas a notch has a finite curvature at each point of the ellipse. In the direction of its largest surface extension, an elliptical shape is also assumed for an internal crack, and a semi-ellipse for a surface crack.

References

| [1] | Morgner, W.: Wechselwirkungen zwischen ZfP und Bruchmechanik oder „Alles über den Riss“. In: Berichtsband 65 „ZfP und Bruchmechanik“. DGZfP Berlin (1998), (ISBN 3-931381-26-9) |

| [2] | Deutsch, V.; Morgner, W.; Vogt, M.: Magnetpulver-Rissprüfung: Grundlagen und Praxis. VDI Verlag, Düsseldorf (1993), (ISBN 978-3-540-62322-9) |

| [3] | Blumenauer, H.; Pusch, G.: Technische Bruchmechanik. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig Stuttgart (1987) 2nd Edition (see AMK-Library under E 29-2) |

| [4] | Sähn, S.; Göldner, H.: Bruch- und Beurteilungskriterien in der Festigkeitslehre. Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig Köln (1993), (ISBN 3-343-00854-0; see AMK-Library under E 26) |

Short cracks

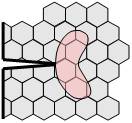

- microstructurally short cracks ( crack length » microstructural characteristics)

- mechanically short cracks ( plastic zone » crack length)

- physically short cracks ( plastic zone << crack length, LEFM) crack closure not fully developed)

- long cracks ( plastic zone << crack length, LEFM crack closure fully developed)

References

| [1] | Suresh, S., Ritchie, R. O.: Propagation of Short Fatigue Cracks. Intern. Mater. Rev. 29 (1984) 445–475 (DOI: doi/abs/10.1179/imtr.1984.29.1.445) |

| [2] | Suresh, S.: Fatigue of Materials. Cambridge Univ. Press (1998) (ISBN 0-521-57046-8) |

| [3] | Blumenauer, H.; Pusch, G.: Technische Bruchmechanik. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig Stuttgart (1987); 2nd Edition (see AMK-Library under E 29-2) |

| [2] | Christ, H. J.: In: Pohl, M. (Eds.): Konstruktion, Werkstoffentwicklung und Schadensanalyse. Tagung Werkstoffprüfung (2010), Neu-Ulm, 02.–03. Dezember 2010, Tagungsband pp. 1–10 (ISBN 978-3-514-00778-9; see AMK-Library under M 18) |

Crack initiation

Crack initiation is basically the transition from a stationary crack to a moving crack. Starting from micro-defects in the material volume, the stress concentrations occurring cause the fracture strength to be exceeded locally and thus initiate a crack. This is followed by either crack propagation or crack arrest. Crack initiation is often preceded by crack blunting (see: crack resistance curve).

The fracture mechanics test makes it possible to determine characteristic values with which the material resistance to crack initiation can be characterised.

Crack propagation

Crack propagation is a physical process that occurs under certain conditions in a moulded part or component after crack initiation and can lead to macroscopic separation – fracture. Crack propagation occurs when material-dependent limit values, such as the critical stress intensity factor, are exceeded.

In principle, a distinction is made between different types of crack propagation:

- stable crack propagation and

- unstable crack propagation.

Stable crack propagation is characterised by a relatively low crack velocity. In addition, the crack requires additional energy supplied from the outside in order to continue to grow. This is the case with fatigue crack propagation, for example.

In contrast, unstable crack propagation is characterised by crack velocities up to the speed of sound in the material in question. Unstable crack propagation also involves the release of energy.

The fracture surfaces resulting from the different types of crack propagation often differ in terms of their structure and characteristics. This is an important aspect in the context of damage analysis, for example, where conclusions can be drawn about crack propagation on the basis of microfractographic investigations.

In the context of technical fracture mechanics, characteristic values can be determined on the basis of different concepts, which quantitatively describe the material resistance to unstable or stable crack propagation separately from each other.

For plastics, the work of Seidler [1, 2] has shown that morphological changes in polymer materials can have a much greater effect on crack propagation than on crack initiation behaviour. From this point of view, the quantitative inclusion of crack propagation behaviour beyond the limits set by the standards is necessary for the effective use of fracture mechanics, particularly in the field of material development.

See also

- Crack opening

- Crack resistance curve – Experimental methods

- Crack propagation

- Notch

- Notch sensitivity

- Notch geometry

References

| [1] | Seidler, S., Grellmann, W.: Zähigkeit von teilchengefüllten und kurzfaserverstärkten Polymerwerkstoffen. Fortschritts-Berichte VDI-Reihe 18: Mechanik/Bruchmechanik Nr. 92, VDI Verlag GmbH, Düsseldorf (1991) (ISBN 3-18-149218-3; see AMK-Library under A 4) |

| [2] | Seidler, S.: Anwendung des Risswiderstandskonzeptes zur Ermittlung strukturbezogener bruchmechanischer Werkstoffkenngrößen bei dynamischer Beanspruchung. Habilitation (1997). Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. VDI Verlag GmbH, Düsseldorf (ISBN 3-18-323118-2; see AMK-Library under B 2-1) |