Tensile Test Residual Stresses Orientations

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Tensile test residual stresses orientations

Influence of residual stresses and orientations

The material value level of plastics depends to a large extent on external factors such as the test speed and temperature, as well as the test climate and test specimen geometry, which are generally summarised under the term test conditions.

On the other hand, the internal state of the test specimen also influences the level of the characteristic values, with residual stress and orientation being particularly noteworthy here, which in turn depend on the manufacturing or processing method and its process conditions [1].

Residual stress

Residual stresses in plastic moulded or components tend to occur when these parts are manufactured from molten granulate, e.g. by extrusion, injection moulding or rotational moulding, with this effect being particularly pronounced in the injection moulding process. The reason for this is that after melting, homogenising and degassing, the melt is injected under high pressure into a closed mould, where it cools and is then ejected from the tool. The influence increases with the thickness of the moulded parts (see: moulding compound), whereby similar effects can also occur when welding plastics (see: heterogeneity and laser heterogeneity of strain distribution).

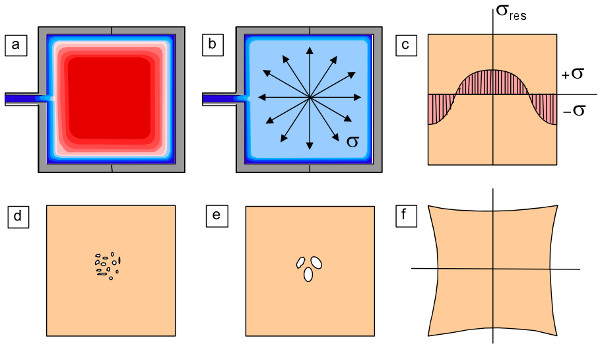

| Fig. 1: | Diagram showing the formation of residual stresses during the injection moulding process |

Once the injection process and the holding pressure phase are complete, the melt freezes on the comparatively cold wall of the tool and in the sprue (Fig. 1a), resulting in a constant volume in the finished mould. Since the volume in the molten state is greater than in the cooled moulded part (see: moulding compound), more or less strong tensile stresses form inside the moulded part as it cools, while the outer part of the moulded part wall exhibits compressive stress (Fig. 1b). Normally, these internal stresses are in equilibrium and dissipate over time, especially at higher temperatures (tempering) (Fig. 1c). However, if they exceed material-specific limits, crazing, micropores or microcracks (Fig. 1d) may form, which ultimately create macroscopic cavities inside the moulded part that are relevant to failure (Fig. 1e). If the moulded part is thin, warping (see: Shrinkage) may also occur (Fig. 1f).

Orientations

Orientation can be roughly divided into macromolecule orientation and the orientation of additives such as short fibres (glass fibre, carbon fibre or mineral fibre) or particles (talc, chalk or mica), whereby the orientation effects are rather low in organic and inorganic fillers.

The orientation of macromolecules can occur during the manufacturing process through injection moulding, extrusion or blow moulding, whereby this process can take place in the molten state or in the solidified state. This means that the orientation of macromolecules can also be induced mechanically, by uniaxial stretching in the calendering or extrusion process, as well as biaxial stretching during film blowing. Orientation can also be increased, for example, in tensile tests on ductile, stretchable plastics at comparatively slow test speeds (cold flow).

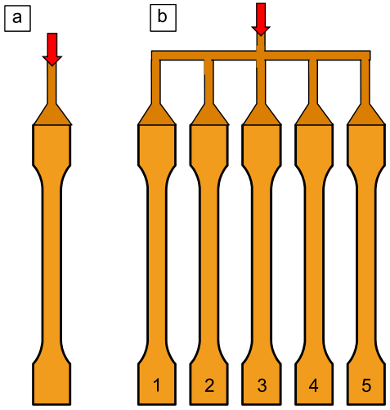

In the case of fillers or reinforcing materials with a fibrous or platelet-like geometry (GF, CF or MF as well as mica), the orientation is also created during the manufacturing process. In the extrusion process and especially in the injection moulding of reinforced plastics, the flow conditions in the tool result in an orientation gradient in the longitudinal, width and thickness directions (see: layer model of fibre orientation), which depends on the thickness and geometry of the component, the injection conditions (temperature and pressure), the fibre volume fraction (viscosity) and the flow path length of the melt. If we consider the production of multipurpose test specimens in the injection moulding process (Fig. 2), we see differing orientations when comparing a 1- nest and a 5-nest tool, as well as depending on the position in the multi-nest tool, since the flow path length and thus the shear (see: shear viscosity) of the melt show significant differences. The characteristic values of the tensile test can only be compared for identical positions in the mould.

| Fig. 2: | Orientation of fillers depending on the flow path length for a single-nest mould (a) and a multi-nest mould (b) |

The fibre orientation of injection-moulded plates and multipurpose test specimens cannot be compared with each other due to the geometry of the sprue channel. The plates exhibit clearer orientation states, but these show greater anisotropy in the longitudinal and transverse directions [2].

Influence on material values of the tensile test

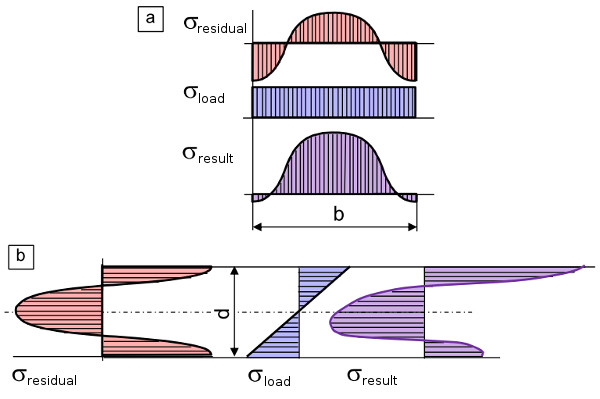

The residual stresses in test specimens have a particular effect on the determination of elastic characteristics such as the modulus of elasticity and Poisson's ratio, as small load stresses cause the stress components to overlap (Fig. 3), which is not taken into account in the calculation of the characteristics. In the tensile test (Fig. 3a), this superposition causes a higher tensile stress in the core of the test specimen, while a slight compressive stress occurs in the outer area. In the bend test (Fig. 3b), the distribution of the load stress and the residual stresses results in a complex stress distribution that changes with increasing stress. A clear assignment of a neutral fibre is no longer possible in the initial stage of this test. With increasing load stress, the influence of residual stresses decreases, provided that certain limit values for environmental stress cracking formation are not exceeded.

| Fig. 3: | Influence of the residual stress distribution in the multipurpose test specimen on the resulting stress in the tensile test (a) and in the bend test (b) |

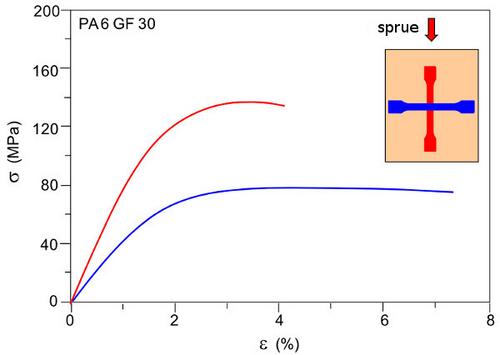

In contrast to the residual stresses, the orientations of the macromolecules and additives affect the elastic constants as well as the strength and deformation behaviour. In Fig. 4, this influence is shown for polyamide 6 with 30 M.% short glass fibres (abbreviation: PA 6) using averaged stress–strain diagrams (see: tensile test) for the longitudinal (red in Fig. 4) and transverse (blue in Fig. 4) directions. The 1.5 mm thick plates were injection moulded, and the test specimens were then produced by sawing and milling. It is clear to see that the tensile strength in the longitudinal direction of the short glass fibres is almost twice as high as in the transverse direction. In terms of elongation at break, the ratios for the characteristic values are the reverse of those for strength.

| Fig. 4: | Influence of orientation on tensile strength and elongation at break [3] |

See also

- KNOOP hardness

- Thermal expansion coefficient

- Tensile test event-related interpretation

- Shrinkage

- Shrinkage test

Referecnces

| [1] | Bartnig, K.: Probekörperherstellung und Probekörpervorbereitung. In: Schmiedel, H. (Eds.): Handbuch der Kunststoffprüfung. Carl Hanser, Munich Vienna (1992) (ISBN 978-3-446-16336-2; see AMK-Library under A 3) |

| [2] | Bierögel, C.: Prüfkörperherstellung. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, pp. 15–38 (ISBN 978-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [3] | Illing, R.: Bewertung von mechanischen und thermischen Eigenschaften glasfaserverstärkter Polyamid-Werkstoffe unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Alterungsverhaltens von Bauteilen in der Automobilindustrie. Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Dissertation (2015) Shaker Verlag GmbH Aachen, (ISBN 978-3-8440-4212-2, 198 Seiten, 128 Abbildungen; see AMK-Library under B 1-27) |