Continuous Vibration Test

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Vibration test, continuous vibration test or cyclic loading test

Thermal failure

The work to be applied per unit volume during a sinusoidal stress in a fatigue test consists of two components: the elastically stored work W', which is recovered as mechanical work during unloading, and the loss work W'', which is converted into heat.

The loss work, relative to 1 cycle, is calculated as

or, per unit of time, as

The loss angle δ is generally less than 15° for polymers. Therefore, sin δ can be set equal to the loss factor d = tan δ, which is also temperature-dependent. For the stress-controlled fatigue test (σm = const.), the following then applies:

and for the strain-controlled fatigue test (εm = const.), the following applies:

with

| E' | real part of the modulus of elasticity of the fatigue test |

The test specimen will then fail thermally under oscillating stress when the point under the highest stress reaches the softening temperature. This is the case when the heat W'' generated by the internal damping of the material is greater than the amount of heat Q dissipated.

| with: | α | – | heat transfer coefficient |

| f | – | shape factor surface/cross-section | |

| ϑ | – | test specimen temperature | |

| ϑ1 | – | ambient temperature | |

| k | – | correction factor internal temperature |

This results in the following conditions for thermal failure with W'' > Q for σm = const.:

and for εm = const.

The factor k takes into account the temperature in the test specimen cross-section.

| k = 1: | temperature is the same across the entire cross-section |

| k = 0.5: | good heat conduction |

| k > 1: | heat accumulation |

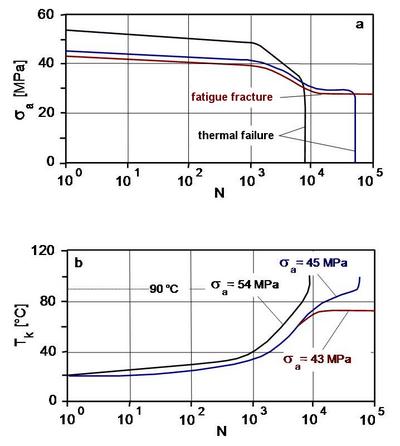

The heating behaviour varies greatly between individual plastics, as shown in Fig. 1 below.

| Fig. 1: | Heating in continuous vibration testing using polycarbonate (abbreviation: PC) and polyamide (abbreviation: PA) as examples [1] |

The specified relationships can be used to calculate the magnitude of the stress at which no additional heating occurs or to determine the equilibrium temperature that occurs at a given stress magnitude.

If the heat transfer coefficient α and the factor k cannot be derived from empirical values, k²/α is determined experimentally in a continuous vibration test with a constant load cycle number N, constant form factor f and constant ambient temperature.

Influences

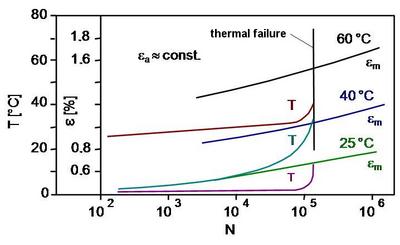

In plastics, the WÖHLER curve (S–N curve) shifts to lower load limits due to notches, weld true, increased frequencies, larger cross-sections and medial stresses. Increased load-bearing capacity can be expected with increasing molecular orientation, in composites with increased fibre orientation, with favourable heat dissipation and during load breaks (Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2: | Hysteresis and factors influencing the S–N curve [2] |

In general, the fatigue strength of plastics is only set at 20 % to 30 % of the tensile strength, whereas for structural steels this value is 60 % to 80 %.

When using the test method described to determine the fatigue strength, the deformation behaviour of the materials to be tested must be taken into account. In plastics, the deformation behaviour is at least time-dependent, i.e. the stress applied does not immediately produce a corresponding deformation, but the deformation that occurs is delayed. Under cyclic loading, this results in a hysteresis loop in the stress–strain diagram (hysteresis test method).

This means that the deformation energy stored by the test specimen is not completely recovered during the return deformation, so additional energy must be applied for the return deformation. A certain amount of deformation work is absorbed during each load cycle. This is proportional to the area enclosed by the hysteresis loop and is converted into heat. The low thermal conductivity of plastics plays a significant role here. Continuous vibration tests on plastics therefore lead to heating of the test specimens, which causes a decrease in the modulus of elasticity and an increase in creep and relaxation effects.

In order to ensure constant test conditions, the test parameters must therefore be monitored and deviations adjusted. In addition, depending on the type, stress and cooling options, the frequency for plastics is limited to 500 to 3,000 load cycles per minute (50 Hz).

Regulation

The control of continuous vibration tests is complicated in that, on the one hand, the amplitude (stress or strain variation) must be controlled, while on the other hand, in the case of plastics, the mean stress decreases or the mean strain increases as a result of relaxation or retardation. The control of the amplitude therefore corresponds to control loop 1 and that of the respective mean value to control loop 2. Since the modulus of elasticity or compliance does not remain constant due to material damage, but serves as a basic setting parameter, the control behaviour may also change. In modern testing systems, a third control loop is therefore implemented to monitor the stiffness of the test specimen (see: specimen compliance) and continuously adjust the control parameters in the event of changes. Regardless of the display of the signal behaviour on the monitor of the connected computer, monitoring of the analogue or incremental output signal using an oscilloscope should not be dispensed with, as signal processing such as filtering or smoothing can lead to a changed signal curve.

The following control variables can be set for oscillating loads:

- proportional amplification P'

- integral amplification I

- derivative amplification D

The P-part in particular has a major influence on the stability of the control system:

| with: | A0 | – | initial amplitude |

| A1 | – | new amplitude | |

| Af | – | control deviation of the amplitude | |

| P | – | proportional amplification |

The quality of the control depends largely on the time response of the control loop. The difference between the setpoint and actual signal (control deviation) is amplified, integrated and differentiated depending on the PID setting. Too high a P part always leads to control loop instability.

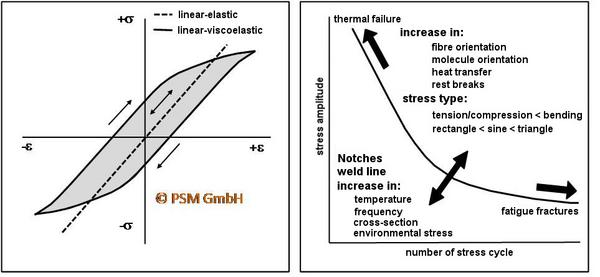

Example

In the case of bend loading, heat is generated at the point of greatest stress, i.e. the surface, while heat derivation is also easier. In addition, the stresses relax more quickly there, so that higher-frequency dynamic loads are possible overall. If stresses are reduced at the surface or if cracks even occur, the cross-section and thus the moment of resistance or the stresses will decrease with the 2nd power. Due to the reduction in stress, the flexural fatigue test (strain-controlled) is then continued at a significantly lower flexural stress level. Flexural fatigue tests therefore often result in higher, fictitious strengths at higher load cycles than tensile fatigue tests, as the level of stress remains constant in stress-controlled tests.

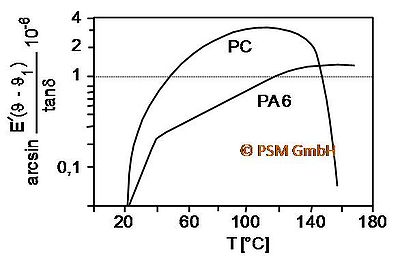

The following Fig. 3 shows the results of the vibration test on polymethyl methacrylate (abbreviation: PMMA) under bend loading in the alternating range and constant mean strain.

| Fig. 3: | Bending vibration test on PMMA; stress amplitude (a), temperature at the test specimen surface (b) [3] |

When εm and εa = const., the stress amplitude at the start of the test decreases with increasing number of load cycles. The same applies to the modulus of elasticity. At the same time, the level of the stress amplitude at the start of the test causes an increase in the test specimen temperature, which can lead to thermal failure.

In the example shown, this occurs at stress amplitudes of 45 MPa and 54 MPa, as test specimen temperatures of approx. 90 °C are reached. At a stress amplitude of 43 MPa, the heat generated by internal damping and the heat dissipated are in equilibrium, resulting in fatigue failure.

The following Fig. 4 shows the results of continuous vibration tests in the tensile threshold range on glass fibre-reinforced polyamide (abbreviation: PA/GF). The load cycle frequency was 7 Hz, the stress amplitude 36 MPa and the mean stress 38 MPa.

| Fig. 4: | Continuous vibration test in the tensile stress range on PA/GF; stress amplitude (a), temperature on the test specimen surface (b) [3] |

See also

- Fatigue

- Test specimen for fatigue tests

- Vibration strength

- Vibration-induced creep fracture

- Vibration fracture

References

| [1] | Oberbach, K.: Das Verhalten von Kunststoffen bei kurzzeitiger und langzeitiger Beanspruchung, Kennwerte und Kennfunktionen. Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik 2 (2004) 65, pp. 281–291 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/mawe.19710020602 |

| [2] | Oberbach, K.: Schwingfestigkeit von Thermoplasten – ein Bemessungskennwert ?. Kunststoffe 77 (1987) 4 pp. 409–414, see Deutsche Nationalbibliothek |

| [3] | Dallner, C., Ehrenstein, G. W.: Thermische Einsatzgrenzen von Kunststoffen, Part II: Dynamisch-Mechanische Analyse unter Last. Zeitschrift Kunststofftechnik 2 (2006) 4 pp. 1–33 Download als pdf |

Further References

- Baur, E., Brinkmann, S., Schmachtenberg, E.: Saechtling Kunststoff-Taschenbuch. Carl Hanser, Munich Vienna (2008) 30th Edition (ISBN 978-3-446-40352-9)

- Oberbach, K.: Das Verhalten von Kunststoffen bei kurzzeitiger und langzeitiger Beanspruchung, Kennwerte und Kennfunktionen. Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik 2 (2004) 65, pp. 281–291 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/mawe.19710020602

- Hellrich, W., Harsch, G., Haenle, S.: Werkstoff-Führer Kunststoffe, Eigenschaften – Prüfungen – Kennwerte. Carl Hanser, Munich Vienna (2004) 9th Edition (ISBN 3-446-22559-5)

- Becker, G. W., Braun, D., Carlowitz, B.: Die Kunststoffe. Chemie, Physik, Technologie, Kunststoff-Handbuch Volume 1. Carl Hanser, Munich Vienna (1990) 1st Edition (ISBN 978-3-4461-4416-1)

- Ehrenstein, G. W.: Faserverbund-Kunststoffe, Werkstoffe – Verarbeitung – Eigenschaften. Carl Hanser, Munich Vienna (2006), 2nd Edition (ISBN 978-3-446-22716-3; see AMK-Library under G 6-2)

- Bargel, H.-J., Schulze, G.: Werkstoffkunde. Springer Berlin Heidelberg 11th Edition (2012) (ISBN 978-3-642-17716-3; see AMK-Library under L 43)

- Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Kunststoffprüfung. Carl Hanser, Munich (2025) 4th Edition, p. 165 and p. 170 (ISBN 978-3-446-44718-9; E-Book: ISBN 978-3-446-48105-3; see AMK-Library under A 23)

- Erhard, G.: Konstruieren mit Kunststoffen. Carl Hanser, Munich (2008) 4th Edition, (ISBN 978-3-446-41646-8; see AMK-Library under G 59)

- Renz, R., Altstädt, V., Ehrenstein, G. W.: Schwingfestigkeitsverhalten von faserverstärkten Kunststoffen (SMC); Faserverbundwerkstoffe. Volume III, Springer, Berlin (1986), pp. 441–518 (ISBN 978-3-642-82624-5)

- Oberbach, K.: In: Henkhaus, R.: Schwingfestigkeit von Kunststoffen. DVM, 1. Sitzung des AK „Polymerwerkstoffe“ Frankfurt/M., 21 and 22 October 1986, Proceedings pp. 25–40 (see AMK-Library under C 15)

![{\displaystyle A_{1}-A_{0}\,=\,\left[1-{\frac {A_{f}}{100}}\right]P}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/60d70f66b365133b2a067f2a94ba5aeb8065f455)