Anisotropy

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Anisotropy

Definition

In physics, and in particular in materials technology and materials testing, the term anisotropy generally refers to the directional dependence of material-specific properties. This directional dependence may be due to the composition or structure of the materials, their manufacturing process, or it may be deliberately used as a design and dimensioning tool. If there is no directional dependence, the material is referred to as isotropic. This property of materials is not related to the heterogeneity of the material properties.

Anisotropy can affect various physical or material properties, such as the optical, acoustic and thermal wave propagation velocity, thermal length change, electrical conductivity, strength, deformation, hardness and elasticity characteristics, or even fracture mechanics characteristics, which describe crack initiation and propagation behaviour. For example, the optical light radiation of an incandescent lamp is isotropic, but that of laser light is anisotropic, and both optical and acoustic birefringence (see: ultrasonic birefringence) are fundamentally based on anisotropy of the index of refraction. Due to the direction-dependent crystallite arrangement in metals and, to some extent, in semi-crystalline plastics, these materials exhibit anisotropies in their elastic properties, such as the modulus of elasticity, as well as in their plastic deformability and ductility, e.g. deep-drawing ability, which are taken into account in structural applications with direction-dependent deformation and elasticity laws. Wood exhibits natural anisotropy due to its biological structure, which must be taken into account, for example, when using natural fibres or constructing with wood. Due to the anatomy of wood, different properties occur in the axial, tangential and radial directions, which influence almost all physical properties of wood. This particularly affects strength, swelling (see: water absorption) and shrinkage during drying processes.

Anisotropy of unfilled and filled plastics

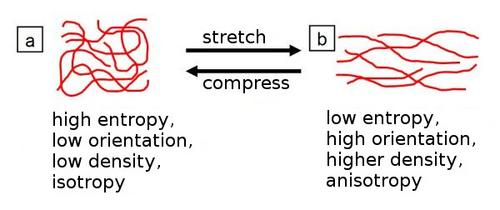

In unfilled or particle-filled plastics, anisotropies occur as a result of the processing conditions in injection moulding, extrusion, calendering or blow moulding of films, primarily due to the orientation of the macromolecules in the amorphous areas (Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1: | Amorphous plastic in a) unoriented and b) oriented state |

The degree of anisotropy is determined by the orientation produced, is associated with a reduction in entropy and is significantly influenced by the degree of elongation. Anisotropy can be seen, for example, in extruded tubes or sheets, where increased strength and elastic modulus are measured in the extrusion or calendering direction, or in biaxially stretched blown films, which exhibit a higher level of strength in the main deformation axes. Anisotropy effects can be influenced by heat treatment (tempering), as at temperatures close to the glass transition temperature TG, the orientation is reset by shrinkage processes, although this often results in warping of the component concerned. The existing anisotropy in such materials can be measured using thermal expansion in different directions or, in the case of transparent plastics, using optical testing methods [1]. However, the state of anisotropy can also be assessed using mechanical testing methods, such as KNOOP hardness [2] or tensile testing.

Anisotropy of fibre-reinforced thermoplastics

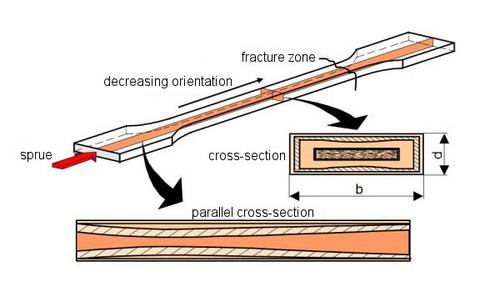

In short- or long-fibre-reinforced thermoplastics (e.g. glass, carbon or aramid fibres), the degree of anisotropy is determined by the orientation of the fibres in the direction of stress. The processing conditions of these materials, preferably in extrusion or injection moulding, result in an orientation profile in the cross-section and longitudinal direction, which is significantly influenced by the layer structure of the fibre distribution (see: glass fibre orientation) [3] (Fig. 2). As the thickness of the injection-moulded parts decreases and the flow path length increases, the orientation and degree of anisotropy increase as a result of the increased shear of the melt in the sprue channel and mould [4].

| Fig. 2: | Formation of orientation in fibre-reinforced plastics |

Experience shows that the difference in characteristic values in the longitudinal and transverse directions for PP/GF injection-moulded parts can be a factor of 2 for tensile strength and up to a factor of 3 for the modulus of elasticity in tensile testing. With locally resolving test methods, such as laser extensometry, even greater differences can be detected based on the heterogeneity within a test specimen [5]. In principle, tensile testing [6] as a mechanical test method and non-destructive test methods such as ultrasonic birefringence, microwaves or eddy currents [7] are suitable for detecting orientations and thus anisotropy in fibre-reinforced plastics (FRP).

Anisotropy of fibre-reinforced thermosets

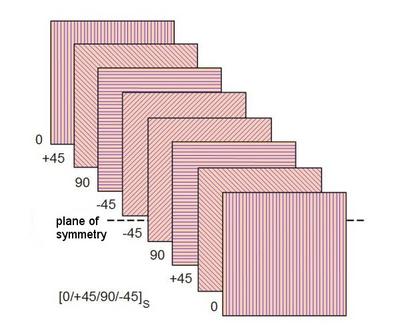

In fibre-reinforced thermosetting plastics, a defined anisotropy is often deliberately achieved by arranging the fibres or mats in order to meet the requirements of the aerospace and automotive industries for optimum lightweight construction and functionality. To this end, the fibres are ideally oriented in the longitudinal direction, e.g. as continuous fibres (rovings) in the pultrusion process, or so-called prepregs (pre-impregnated fibres) with a known fibre orientation are inserted in the main load direction of the components, fixed in place and cured in an autoclave in a closed or open mould. Similar technologies, such as winding pipes or containers or the lamination process, can also be used to manufacture components with defined anisotropies, but also with a heterogeneous structure, whereby the fibres are usually oriented in the main load direction. When using random fibre fabrics, unidirectional (UD) fabrics parallel to the main load directions or multi-layer laminate structures (Fig. 3), fibre composites with a very low degree of anisotropy (orthotropic in the case of UD fabrics) are produced. The highest degrees of anisotropy are achieved with roving structures [8]. Almost all reactive resins are suitable as matrix materials, although UP or EP resins are usually used for high-quality applications. In these cases, glass or carbon fibres are usually used as reinforcing materials (see: fibre-reinforced plastics).

| Fig. 3: | Schematic structure of an 8-layer laminate made of prepreg layers [8] |

When the structure is known, the degree of anisotropy is usually determined by the elastic properties (modulus of elasticity and Poisson's ratio) of the laminate layers, so that a modified stiffness matrix based, for example, on transverse isotropy is used for simulation calculations, which is based on St. Venant's theory. More detailed information on designing with FRP can be found in [9]. In terms of measurement technology, the degree of anisotropy is only accessible to a limited extent, as only very small test specimens can be used in the thickness direction of the laminate, whereas the longitudinal and transverse directions can be easily examined with tensile test specimens.

See also

- Fibre orientation

- Film testing

- Glass fibre orientation

- KNOOP hardness

- Composite materials testing

- Tensile test residual stresses orientations

References

| [1] | Trempler, J.: Optical Properties. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022), 3rd Edition pp. 299–330 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [2] | Grellmann, W.: Hardness Test Methods. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022), 3rd Edition pp. 180–182 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [3] | Menges, G., Geisbüsch, P.: Die Glasfaserorientierung und ihr Einfluss auf die mechanischen Eigenschaften thermoplastischer Spritzgussteile – Eine Abschätzmethode. Colloid & Polymer Science 260 (1982) 1, pp. 73–81 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01447678 |

| [4] | Illing, T.: Bewertung von mechanischen und thermischen Eigenschaften glasfaserverstärkter Polyamid-Werkstoffe unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Alterungsverhaltens von Bauteilen in der Automobilindustrie. Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Dissertation (2015), Shaker Publishing Aachen (2016) (ISBN 978-3-8440-4212-2; see AMK-Library under B 1-27) |

| [5] | Grellmann, W, Bierögel, C.: Laserextensometrie anwenden – Einsatzmöglichkeiten und Beispiele aus der Kunststoffprüfung. Materialprüfung 40 (1998) 11-12, pp. 452–459 |

| [6] | Jäger, S.: Einfluss der Faserorientierung auf das mechanische Kennwertniveau medial und thermisch beanspruchter Polypropylen-Glasfaser-Verbunde. Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Diplomarbeit (2010) (see AMK-Library under B 3-168) |

| [7] | Busse, G.: Non-destructive Polymer Testing. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022), 3rd Edition pp. 431–495 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [8] | Altstädt, V.: Testing of Composite Materials. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022), 3rd Edition pp. 515–567 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [9] | Schürmann, H.: Konstruieren mit Faser-Verbund Kunststoffen. Springer, Berlin (2007), 2nd Edition (ISBN 978-3-540-72189-5) |