Sound Velocity

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Sound velocity

General remarks

The sound velocity is an essential property of the medium through which sound travels and describes the time it takes for a wave or wave packet to travel the distance between two points in the medium. This parameter is a basic parameter of ultrasound testing.

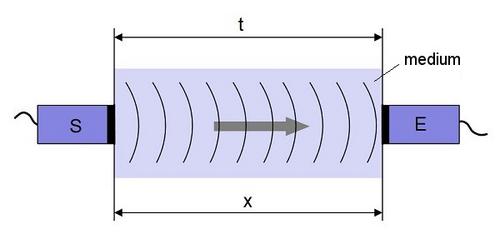

In the simplest case, it is described by the path–time law, which is explained schematically in Fig. 1. Here, sound waves are transmitted through a medium by means of a transmitter or sound generator (ultrasonic sensors or also referred to as a probe) that emits the sound pulse. At the end of the transmission path is the receiver (ultrasonic sensors), which should be of the same design as the transmitter (see: ultrasonic transmission technique). The electrical pulses sent to the transmitter S are converted into mechanical pulses, transmitted by the medium as waves and received by the receiver E (transmission technique). The time t required by the sound to travel the path x can be determined from the representation of the vibrations registered at the receiver according to Eq. (1).

| Fig. 1: | Schematic presentation of a sound velocity measurement between a transmitter S and a receiver E |

| (1) |

When calculating the sound velocity, however, it should be noted that, depending on the design of the ultrasonic sensors, the direction of sound incidence and the properties of the medium, longitudinal waves and/or transverse waves can be generated, each of which has a different propagation velocity. This is illustrated by the indices L (longitudinal) and T (transverse) of the sound velocity c in Eq. (1).

Longitudinal and transverse waves

Sound can propagate in a solid volume at two different velocities, corresponding to the two sound velocities of the longitudinal and transverse waves. This results from the consideration of a model lattice structure that embodies the behaviour of solids. Even with perpendicular sound incidence, echoes of transverse waves are produced, which are caused by the slight asymmetry of the sound field that is practically always present. In most cases, however, this influence is small and the amplitude of the longitudinal waves predominates. However, this circumstance must be taken into account in order to avoid misinterpretations of the measured HF-scan with regard to the signal transit time.

The following Table 1 shows the sound velocities of longitudinal waves in selected metals and plastics for comparison.

| material | sound velocity cL (m s-1) |

|---|---|

| Stahl | 5,900 |

| Aluminium | 6,400 |

| Messing | 4,300 |

| Synthetischer Kautschuk | 1,460 |

| PMMA | 2,540 |

| PS | 2,350 |

| PVC | 2,300 |

| PA6 | 2,570 |

| PP | 2,550 |

| PE | 1,800 |

| UP-Harz Derakene 411 | 2,400 |

| UP-Harz Derakane 470 | 2,700 |

| UP-Harz Derakene 411 + 36 M.% GF | 2,510 |

| UP-Harz Derakene 411 + 70 M.% GF | 3,050 |

Longitudinal waves are used in ultrasound testing for wall thickness measurement and direct defectoscopy, while transverse waves are used for indirect defectoscopy, e.g. for assessing bonded and welded seams (see: ultrasonic weld inspection).

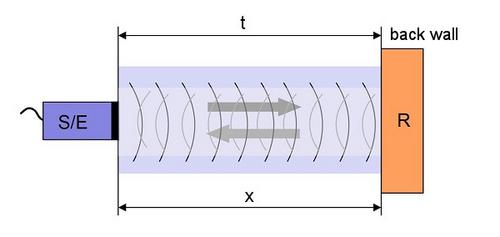

Figure 1 shows the simplest variant of sound velocity measurement using the transmission technique. However, due to design or geometric constraints, it is often necessary to test only one side of the component. The pulse-echo technique, which is widely used in ultrasound testing, is suitable for this purpose. In this case, the transmitter probe also functions as a receiver (see: pulse-echo technique). The sound waves travel the distance to the reflector R and back, which is why the distance x is entered twice in Eq. (2) (Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2: | Schematic presentation of a sound velocity measurement using the pulse-echo technique |

| (2) |

This method is particularly suitable for measuring very thin components or layers, provided that the sensor technology allows this. The sensor should be designed in such a way that wavelengths in the order of magnitude of the layer thickness can still be achieved. According to the equation c = λ · f, the test frequency must be selected appropriately high for small layer thicknesses so that these can still be resolved in the A-scan.

Measurement of sound velocity

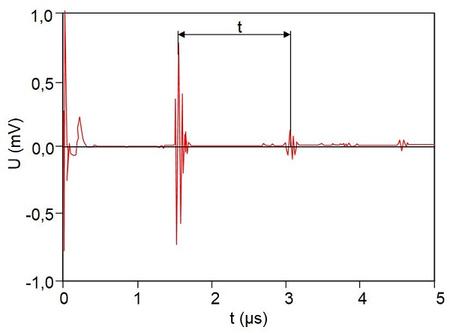

The sound velocity is determined at a known distance x by measuring the time using an HF-scan or A-scan. These scans represent the voltage pulses into which the sound pressure amplitude is converted by the piezoelectric effect. Figure 3 shows an example of an HF-scan in which two echoes are illustrated. Usually, the sound transit time between the two echoes is measured in order to determine the sound velocity using the known thickness of the component layer to be examined.

| Fig. 3: | Voltage pulses for measuring the transit time on a plane-parallel PMMA plate using pulse-echo technique with ultrasound |

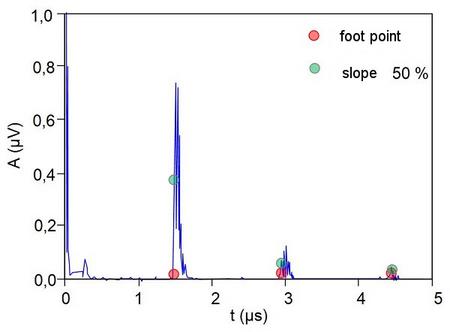

| Fig. 4: | Measurement on a PMMA plate using pulse-echo technique with ultrasound |

There are three different approaches to measuring the sound transit time. The first approach uses the signal maxima, as shown in Fig. 3. In most cases, however, the signals are not as ideal as shown in Fig. 3. Therefore, two other evaluation methods are used. A second approach uses the base point of the signal (Fig. 4). This circumvents the difficulty that significant deviations arise when measuring the maxima in cast materials or plastics, because sound dispersion, especially in plastics, causes different frequencies to be transmitted at different velocities, which results in a broadening of the signal.

If signal repetitions are displayed on the measuring device, the individual echoes are similar in shape. This means that the rising edge can also be used for runtime measurement. In Fig. 4, the amplitude value of 50 % of the respective echo height is marked with a green dot. However, other positions on the rising edges can also be used as measuring points. This depends in particular on the shape of the echoes, which, for example, exhibit a vibration behaviour in certain plastics. To evaluate the measured values, digital measuring devices with A-scan display (Fig. 5) should be used, which can determine the sound velocity of the test object if its wall thickness is known (see also: ultrasonic wall thickness measurement).

| Fig. 5: | Digital ultrasonic wall thickness measurement devices with A-scan display (a) Echometer 1077 from Karl Deutsch Prüf- und Messgeräte Bau GmbH und Co KG, Wuppertal (https://www.karldeutsch.de/?lang=en), and (b) FD 20 from PCE Deutschland GmbH Prüfgeräte, Meschede (https://www.pce-instruments.com/) |

Phase and group velocity

The sound velocity is usually specified as the phase velocity. This means that in this case, a sound wave with a fixed frequency (monochromatic) is present. In general, however, sound generation produces wave packets with different frequencies, i.e. the wave packets contain waves with different wavelengths. In this case, there is dispersion, which means that a wave packet contains different waves with different velocities. Therefore, the average propagation velocity of the wave packet is defined as the so-called group velocity, which is measured in practice using the methods described above and corresponds to the phase velocity with only minor deviations.

For elastic and isotropic materials, the sound velocity of the ultrasound in the volume can also be calculated according to Eqs. (3) and (4) if the modulus of elasticity, the density and the Poisson's ratio at the given temperature are known.

| (3) |

| (4) |

See also

References

| [1] | Deutsch, V., Platte, M., Vogt, M.: Ultraschallprüfung – Grundlagen und industrielle Anwendungen. Springer, Berlin (2012), (ISBN 978-3-642-63864-0) |

| [2] | Matthies, K. u. a.: Dickenmessung mit Ultraschall. DVS-Verlag GmbH, Berlin, 2nd Edition (1998), (ISBN 3-87155-940-7; see AMK-Library under M 44) |

| [3] | Langenberg, K.-J., Marklein, R., Mayer, K.: Theoretische Grundlagen der zerstörungsfreien Materialprüfung mit Ultraschall. Oldenbourg Publishing, Munich (2009), (ISBN 978-3-48658-881-1) |