Particle-filled Thermoplastics

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Particle-filled plastics

Definition

The terms “particle-filled plastics” or “particle-plastic composites” are synonymous with an extremely heterogeneous group of materials that are determined by the type of particles, the particle volume fraction and distribution as well as the particle spacing, the possible matrix materials and various manufacturing processes.

In contrast to fiber-reinforced composites, the particles used in filled plastics have no reinforcing effect on strength under tensile, compressive and bending stress. Depending on the filler volume fraction, however, an increase in the modulus of elasticity is achieved, although the tensile strain at break of the filled plastics then decreases considerably.

In principle, a particle-polymer composite is a combination of any particles of different geometry and origin and a polymer matrix that envelops the fillers and enables force transmission between the respective composite partners by means of adhesive or cohesive interaction.

The added particles can be inorganic or organic particles that have regular or irregular shapes and generally serve to stretch the polymer (cost reduction) or functionalize it (electrical and temperature conductivity, hardness, abrasion). A distinction is also made between macro-, micro- and nanoparticles, which vary in particular in terms of filler content, particle size and spacing in the composite as well as their geometry and structure.

As most plastics are not suitable for structural applications due to their low strength, high tensile strain at break (see: tensile strength) and shrinkage due to their viscoelastic properties (thermoplastics) or very low tensile strain at break and brittle fracture behaviour (thermosets), reinforcement with fibres or filling with functional particles represents an economical variant for the production of materials with specially adapted properties (e.g. in dental technology).

Due to the variability of the fillers and plastics, the properties of these composites can be specifically adjusted over a wide range (“tailor-made materials”), making applications in the lightweight construction sector for the white goods and automotive industries possible in the first place.

Regardless of the type of filler and the selected matrix, particle-filled plastics have an increased specific modulus of elasticity (characteristic value in relation to density), higher hardness and improved tribological properties than the matrix material, but they generally have reduced tensile strain at break and sometimes also increased anisotropy (directional dependence) of the mechanical and thermal properties due to the particle geometry and manufacturing conditions. If too little filler is added, it acts as a local impurity and stress concentration, which favors micro-crack formation (see: fracture formation) in the composite. Increasing the filler content generally prevents shrinkage behavior, but especially in the case of organic fillers (core–shell particles), optimal volume proportions can also lead to an increase in the dissipation capacity of the composite as a result of microcraze formation (see: craze-types) with an increase in fracture toughness due to stable crack growth [1–9].

The basic rule for all particle-filled plastics is that the fillers take on a supporting or functional role in the composite, while the matrix performs a bedding and protective function, which is why good filler bonding to the respective matrix is also required. This can influence the crystallization behaviour, particularly in the case of semi-crystalline polymers, as they sometimes act as crystallization nuclei (see: crystallinity).

In analogy to reinforcing fibers, the fillers are often also provided with a so-called coating and an adhesion promoter (see also: fibre–matrix adhesion), which improve the bonding of the particles to the matrix and form an interface between matrix and fibre. The l/d ratio of the particles is close to 1, so that fractures of the particles are rather rare and debonding from the matrix is the dominant damage mechanism [10–13].

Technically used fillers

The most commonly used technical fillers for plastics (thermoplastics, thermosets and elastomers) are:

- Talc particles of different sizes and distributions,

- Chalk particles with cubic or spherical geometry,

- Glass flour or powder (GC, GD and GX),

- Glass balls or hollow glass balls (GB),

- Carbon fiber particles, carbon powder (CD) and carbon black (CB),

- Mica of different size and distribution (MI),

- Mineral and ceramic particles (MD, MP and MX),

- Bronze powder (BP),

- Wollastonite (WT),

- Natural fiber and wood flour (NF), e.g. for WPC,

- Elastomer particles based on EPDM and

- Metal particles for the functionalization of plastic composites.

The oldest natural inorganic fillers for plastics are talc and chalk (CaCO3), which are added to essentially minimize costs. At the same time, with improved ecological sustainability, the modulus of elasticity, heat resistance and long-term service temperature increase, in some cases considerably, while the tendency to shrink is significantly reduced. However, the relatively high density of these additives has a disadvantageous effect, as a result of which plastic components have a higher mass. Usually, 7 to approx. 55 wt.-% of talc and 10 to 40 wt.-% of chalk are added to the particle-filled plastics, whereby a significant decrease in tensile strength and tensile strain at break is sometimes observed depending on the filler content. In the case of talc in particular, for example, this depends on the demolition site, the fineness and distribution of the talc particles [14].

The fillers that are used less for stretching the plastic are carbon black (black pigment) and titanium dioxide (white pigment), which can occur as isolated particles or as particle agglomerates and have dimensions ranging from a few nanometers to the µm range. In terms of functionalization, these fillers are used in thermoplastics to influence the color of the base plastics in the white goods and automotive industries, whereby carbon black is also used as a UV stabilizer in plastics and elastomers. In elastomeric materials, however, carbon black (CB), has a reinforcing effect and influences in particular the hardness, abrasion resistance and crack resistance behaviour of tires or conveyor belts, for example [15, 18].

Another mineral or inorganic natural filler which, however, due to its layered and irregular structure, not only has a filling but also a reinforcing effect (l/d ratio of up to 50) in the plastic is the layered silicate mica. The very low electrical conductivity of mica is of particular importance for technical applications as insulator materials, whereby the temperature resistance of plastics (see also: toughness temperature dependence) can also be significantly improved [16].

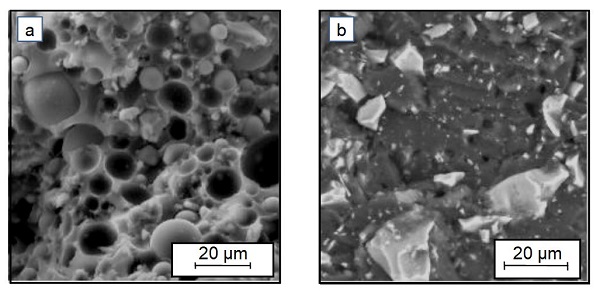

Regularly structured particles are usually spherical or fibrous in shape. These can be very short fibers (mineral fibers – MF, carbon fibers – CF, glass fibers – GF or natural fibers – NF, wollastonite) with a l/d ratio of approx. 1 to 5, or hollow glass spheres (GB) made of microsilicate. The fibers have dimensions in the range from 6 to approx. 13 µm and the hollow balls have diameters in the range from approx. 15 µm to 50 µm. The latter are used in particular to reduce the weight of plastic components and are therefore an alternative to other fillers such as talc, chalk, quartz powder, glass balls or spherical chalk particles (0.05-0.7 µm) (Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1: | Inorganic filler particles in the fracture surface of an EP resin matrix with (a) regular shape (Spheriglass 5000) and (b) irregular habitus (TecoSil 44) [17] |

Irregular inorganic particle structures are usually referred to as flours, powders or dusts. These can be mineral fillers (MD, MP or MX) in addition to talc, quartz or calcium carbonate, which are based on kaolin, amorphous silica or short fibers of carbon, glass or wollastonite as well as broken glass and can sometimes also significantly improve tribological and electrical properties. Ceramic fillers such as boron nitrite (BN – borazon), aluminum oxide (Al2O3), zirconium oxide (ZrO2), silicates or silicon dioxide are generally functional additives which, for example, increase the sliding properties, thermal conductivity as well as the hardness and scratch strength (see: scratch resistance) and are used in dental fillings due to their properties as a ceramic/resin composite. The ceramics zirconium (IV) oxide, titanium (IV) oxide, aluminum titanate or barium titanate as well as silicon (SiC) and boron carbide (B4C) are used in plastic composites due to their hardness for special tribological applications, e.g. in machining processes or grinding techniques.

Metallic powders, such as aluminum flakes or bronze powder, are also used as fillers for various applications, in particular to increase temperature and electrical conductivity.

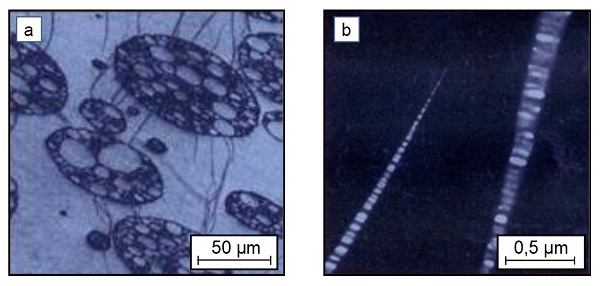

Elastomeric filler particles based on EPDM or EPR, often with a core-shell structure, are used to increase the toughness and energy dissipation of plastics (polypropylene) in automotive engineering [15]. Depending on the particle size and an optimum particle spacing, this results in significantly improved fracture mechanical values, which are based on the propagation of microcrazes (see: micromechanics & nanomechanics) and the stopping of further growth on the elastomer particles (Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2: | Elastomeric filler particles and crazes in a polystyrene matrix (a) and crazes with microfibrils |

In addition to pure reinforced or filled plastics, hybrid composite materials are also produced and used that contain either different fillers or fibers and fillers. These can be combinations of different fibers (GF + CF, GF + NF or CF + MF) or different fillers (GC + CD, GX + CP or GB + MD) as well as fillers and fibers (GF + GB, CF + MD and NF + CD). The damage mechanisms occurring in these hybrid materials can only rarely be precisely determined and described using mathematical methods and models [10–13].

Natural particles or short fibers (NF) are also increasingly being used for filled plastics, although their mechanical properties are comparatively low due to their low density and therefore cannot be used in construction. They are usually only used as fillers for thermoplastics (e.g. WPC-Wood Polymer Compound).

Almost all amorphous and semi-crystalline plastics can be used as thermoplastic matrix materials, although the effect of the filling can vary greatly. The advantage of most thermoplastic matrix materials is the variability of the manufacturing and shaping processes as well as the weldability and bondability. The disadvantage of these filled plastic composites is that they soften and shrink when the glass temperature Tg is reached. However, the tendency of these materials to creep and shrink (see also: shrinkage test) decreases as the filler volume content increases. The anisotropy due to the orientation and the residual stresses are significantly reduced compared to the base plastics.

Matrix material

Suitable thermoplastic matrix materials are e.g:

- polyamide (abbreviation: PA)

- polybutene (abbreviation: PB)

- polycarbonate (abbreviation: PC)

- poly(butylene terephthalate) (abbreviation: PBT)

- polyethylene (abbreviation: PE)

- polyoxymethylene (abbreviation: POM)

- polypropylene (abbreviation: PP).

The following thermoplastics can be used as a matrix for high-temperature applications up to a maximum of 300 °C:

- polyetheretherketone (abbreviation: PEEK)

- poly(phenylene sulfide) (abbreviation: PPS)

- polyether sulfone (abbreviation: PESU)

- polysulfone (abbreviation: PSU)

- polyetherimide (abbreviation: PEI)

- polytetrafluoroethylene (abbreviation: PTFE)

- polychlorotrifluoroethylene (abbreviation: PCTFE)

The resins listed below are used in practice as thermosetting matrix materials, with up to 80 wt.-% filler being added in some cases. The fillers have a long-term effect on the viscosity and therefore the flowability.

- diallylphthalate resin (abbreviation: DAP)

- epoxy resin (abbreviation: EP)

- urea– formaldehyde resin (abbreviation: UF)

- melamine– formaldehyde resin (abbreviation: MF)

- phenol-formaldehyde resin (abbreviation: PF)

- polyurethane (abbreviation: PUR)

- unsaturated polyester resin (abbreviation: UP)

Further information on the mechanical and thermal properties of filled plastics can be found in [19].

See also

- Failure analysis – Basics

- Anisotropy

- Fracture formation

- Craze-types

- Fibre–matrix adhesion

- Processing shrinkage

- Shrinkage test

References

| [1] | Drummer, D., Ehrenstein, G. W., (Eds.): Hochgefüllte Kunststoffe mit definierten magnetischen, thermischen und elektrischen Eigenschaften. Springer VDI Publishing, Düsseldorf (2002), (ISBN 978-3-935-06508-5) |

| [2] | Oberbach, K., Baur, E., Brinkmann, S., Schmachtenberg, E. (Eds.): Saechtling Kunststoff Taschenbuch. Carl Hanser, Munich (2004) 29th Edition, (ISBN 978-3-446-22670-8; see AMK-Library under G 4-1) |

| [3] | Ehrenstein, G. W., Drummer, D. (Eds.): Maschinenelemente aus Kunststoffen – Zahnräder und Gleitlager. Springer VDI Publishing, Düsseldorf (2001) (ISBN 978-3-935-06504-7) |

| [4] | Menges, G., Haberstroh, E., Michaeli, W., Schmachtenberg, E.: Menges Werkstoffkunde Kunststoffe. Carl Hanser Verlag, München (2014), (ISBN 978-3-446-44353-2) |

| [5] | Elsner, P., Eyerer, P., Hirth, T. (Hrsg.) Domininghaus – Kunststoffe, Eigenschaften und Anwendungen. Springer Verlag, Berlin (2012) 8. Auflage, (ISBN 978-3-446-44350-1; see AMK-Library under G 41) |

| [6] | LeBlanc, J. L.: Filled Polymers: Science and Industrial Applications. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton (2009), (ISBN 978-1-439-80042-3) |

| [7] | Münstedt, H.: Rheological and Morphological Properties of Dispersed Polymeric Materials: Filled Polymers and Polymer Blends. Carl Hanser Verlag, München (2016), (ISBN 978-1-569-90607-1) |

| [8] | Bhattacharya, S. K.: Metal-Filled Polymers. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton (1986), (ISBN 978-0-824-77555-1) |

| [9] | Rothon, R.: Particulate-filled Polymer Composites. iSmithers Rapra Publishing, Shawbury (2003), (ISBN 978-1-859-57382-2) |

| [10] | Grellmann, W., Bohse, J., Seidler, S.: Bruchmechanische Analyse des Zähigkeitsverhaltens von teilchengefüllten Thermoplasten. Mat.-wiss. und Werkstofftechnik 21 (1990) 9, pp. 359–364 |

| [11] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S., Bohse, J.: Zähigkeit und Morphologie von Thermoplast/Teilchen-Verbunden. Kunststoffe 81 (1991) 2, S. 157–162 und Toughness and Morphology of Thermoplastic / Particle Composites, Kunststoffe German Plastics 81 (1991) 2, pp. 29–32 |

| [12] | Seidler, S., Grellmann, W.: Bruchmechanische Bewertung der Zähigkeitseigenschaften von teilchengefüllten und kurzfaserverstärkten Thermoplasten. Fortschritt-Berichte, VDI-Reihe 18 Nr. 92, VDI-Verlag Düsseldorf (1991) (ISBN 3-18-149218-3; see AMK-Library under A 4) |

| [13] | Bohse, J., Grellmann, W., Seidler, S.: Micromechanical Interpretation of Fracture Toughness of Particulate Filled Thermoplastics. J. of Material Science 26 (1991) 6715–6721 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00553697 |

| [14] | Schöne, J.: Polypropylen-Talkum-Verbunde – Einfluss von Partikelgröße und Mengenanteil auf das mechanische Eigenschaftsniveau von heterophasigen Propylen-Copolymer-Talkum-Verbunden. Diplomarbeit, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Merseburg (2008) (see AMK-Library under B 3-132) |

| [15] | Reincke, K.: Bruchmechanische Bewertung von ungefüllten und gefüllten Elastomerwerkstoffen. Dissertation, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Merseburg, Mensch & Buch Verlag Berlin (2005), (ISBN 978-3-86664-021-4; see AMK-Library under B 1-13) |

| [16] | Ehrenstein, G. W., Pongratz, S.: Beständigkeit von Kunststoffen. Carl Hanser, Munich (2007), (ISBN 978-3-446-21851-2; see AMK-Library under G 31) |

| [17] | Walter, H.: Morphologie-Zähigkeits-Korrelationen an modifizierten Epoxidharzsystemen mittels bruchmechanischer Prüfmethoden an Miniaturprüfkörpern. Dissertation, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Merseburg, Fraunhofer IRB Verlag Berlin (2003) (ISBN 978-3-8167-6455-7; see AMK-Library under B 1-10) |

| [18] | Seidler, S., Grellmann, W.: Anwendung bruchmechanischer Werkstoffkenngrößen zur Optimierung des Zähigkeitsverhaltens von polymeren Mehrphasensystemen mit PP-Matrix. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Deformation und Bruchverhalten von Kunststoffen. Springer Publishing Berlin (1998) pp. 257–270, (ISBN 978-3-540-63671-7; see AMK-Library under A 6) |

| [19] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Mechanical and Thermomechanical Properties of Polymers. Landoldt Börnstein. Volume VIII/6A2, Springer Publishing, Berlin (2014) (ISBN 978-3-642-55166-6; see AMK-Library under A 16) |