Pure Shear-Specimen

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Pure Shear-specimen

Test specimen shapes for elastomer testing

The Pure Shear-specimen is used alongside the Single-Edge-Notched Bend (SENB) specimen and the Trouser specimen to determine the fracture mechanical properties of elastomer materials [1‒4].

The application of fracture mechanics concepts for the characterization of the deformation and fracture behaviour of elastomers is associated with fundamental difficulties, since elastomers exhibit neither linear-elastic nor elastic-plastic material behaviour. Furthermore, the deformation is not limited to the area in front of and around the crack tip and even highly deformed cracks do not remain sharp as in the Griffith crack model. There is no energy dissipation due to plasticity and the fracture processes are brittle [5].

Tear energy of elastomers according to RIVLIN and THOMAS

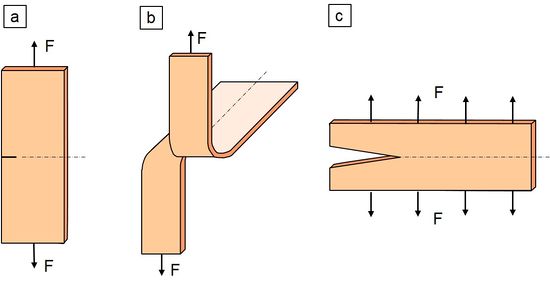

In the fundamental work by Rivlin and Thomas [6], the tearing energy T (Eq. 1) is introduced as a fracture-mechanical parameter for elastomers and the equations of determination Eqs. (2) to (4) are derived for the various specimen geometries (see Fig. 1).

| (1) |

Single-Edge-Notched Tension specimen (SENT):

| (2) |

| (3) |

Pure Shear-specimen:

| (4) |

mit:

| k (λ) = π/ λ1/2 |

| λ = , |

| l – length |

| l0 – initial length |

| W0 – strain energy density and |

| a – initial crack length |

| Fig. 1: | Test specimen shapes for determining the tensile energy T according to Rivlin and Thomas [6] |

SENT specimens have the advantage that they are relatively easy to produce by punching and require less material than Pure Shear-specimens. Due to the fact that they can also be used for the conventional tear test, Trouser specimens are also relatively common for the determination of fracture mechanical properties [7–9]. When using Trouser specimens, it must be taken into account that the stress state before the crack tip is very complex compared to SENT and Pure Shear-specimens. In addition, it must be ensured that all external deformation energy is only used to widen the crack, i.e. there must be no pronounced elastic deformation of the test specimen. Gc or T is often determined according to the following equation when Trouser specimens are used:

| (5) |

If elastic deformation occurs, Eq. (3) must be used to calculate a fracture mechanical material value. However, since elastic deformation of certain areas of the specimen cannot be excluded, Eq. (5) should only be used to estimate the energy release rate G or the tear energy T and SENT or Pure Shear-specimens should be preferred.

The use of Pure Shear-specimen for recording crack resistance (R-) curves

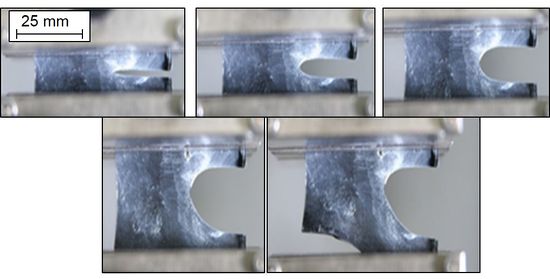

The advantage of the Pure Shear-specimen is that the tear energy T that can be determined with it is independent of the crack length (Eq. 4). This means that T can be determined independently of the crack length even during a crack that grows continuously during loading. This is particularly interesting with regard to the performance of dynamic experiments, but also for the determination of crack resistance curves using the single specimen technique. A disadvantage compared to the SENT-test specimen is the experimental performance of the fracture mechanics experiments with regard to the clamping of the Pure Shear-specimens. Very tough and stiff elastomer materials in particular, such as carbon black-reinforced NR vulcanizates, require special solutions when clamping wide Pure Shear-specimens. If only flat specimens are used here, this can easily lead to slipping effects of the test specimen in the grips and thus to an unacceptable influence on the results. This is clearly illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows images of a test specimen during a continuously increasing quasi-static load.

| Fig. 2: | Increasing stress on a Pure Shear-specimen made of an NR vulcanizate reinforced with 40 phr carbon black during a quasi-static fracture mechanics test with final clamp slippage |

Clamp slippage of the test specimen was observed here at high stresses. This can be counteracted, for example, by using specimens with a bead, but this also means increased effort in the production of the specimens, as it is not possible to simply punch them out of flat sheet material. Special moulds must be available in order to vulcanize such test specimens directly. It should also be noted that the Pure Shear-specimen must not be wider than the clamping clamp. This in turn requires suitable laboratory equipment. The aspect of insertion should also be taken into account when selecting a suitable specimen shape (see notch geometry). The larger the notch to be inserted, the more difficult it is to insert the notch with a metal blade. For Pure shear and Trouser specimens, the notch should therefore already be made during specimen production. Then only a small extension of this notch by a small metal blade notch is required. At the same time, however, this also limits the variation possibilities with regard to the ratio of the initial crack length a0 to the test specimen width W.

Determination of fracture mechanical parameters

The tearing energy, like the energy release rate and the J-integral, is based on an energetic interpretation of the tearing process and is defined as the change in deformation energy required to generate a new surface. For this reason, these three variables are to be regarded as formally identical:

| (6) |

A prerequisite for the equality of J and T is the determination of J under constant displacement [10]. However, Horst [11] made it clear that the energy dissipation associated with crack propagation in elastomers is not limited to the immediate vicinity around the crack tip, but occurs throughout the entire specimen. This fact must be taken into account when characterizing the crack propagation by means of a global energy balance.

For materials that exhibit non-negligible plastic deformation, J-evaluation methods have been derived that take these different deformation components into account [12, 13]. However, this will not be discussed further here, as the materials considered in this study are essentially non-linear visco-elastically deforming materials. J can be determined experimentally using the simplest determination equation (Eq. 7).

| (7) |

mit:

| η – geometry function, |

| A – deformation energy, |

| a0 – initial crack length and |

| W – specimen width |

The geometry function η can either be taken from the literature for the selected test specimen configuration or determined experimentally by applying the compliance method [2, 12‒16].

The diverse areas of application of elastomer materials also result in sometimes very complex stresses on the components during use, which can be mechanical as well as medial or thermal in nature. Particularly with regard to ageing, which inevitably occurs over time, it is necessary to know quantitative structure–property relationships in order to be able to make statements about (residual) service life, for example. Since components often fail due to the formation and propagation of cracks, the quantitative characterization of crack resistance is of great economic importance. The application of fracture mechanics testing based on the above-mentioned concepts is essential here. Fracture mechanical parameters are particularly sensitive to structure and are therefore ideal for establishing structure–property correlations. When experimentally determining fracture mechanics values, it must be taken into account that geometry independence only exists if a plane strain state is present in the specimen, from which certain requirements for the specimen geometry are derived [12, 16].

See also

- Fracture mechanics

- Fracture mechanics test specimen

- Crack resistance curve – Experimental methods

- Crack propagation

- Notch geometry

References

| [1] | Reincke, K.: Elastomere Werkstoffe – Zusammenhang zwischen Mischungsrezeptur, Struktur und mechanischen Eigenschaften sowie dem Deformations- und Bruchverhalten, Habilitation, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Shaker Verlag (2016), (ISBN 978-3-8440-4637-3; see AMK-Library under B 2-2) |

| [2] | Grellmann, W., Heinrich, G., Kaliske, M., Klüppel, M., Schneider, K., Vilgis, T. (Eds.): Fracture Mechanics and Statistical Mechanics of Reinforced Elastomeric Blends. Springer Berlin Heidelberg (2013), ISBN 978-3-662-52184-7; see AMK-Library under A 14 |

| [3] | Stoček, R., Heinrich, G., Gehde, M.: The Influence of the Test Properties on Dynamic Crack Propagation in Filled Rubbers by Simultaneous Tensile‐ and Pure‐shear‐mode Testing. In: Heinrich, G., Kaliske, M., Lion, A., Reese, S., (Eds.): Constitutive Models for Rubber VI, CRC Press (2009) 345–352 |

| [4] | Stoček, R.: Dynamische Rissausbreitung in Elastomerwerkstoffen. Dissertation, Technische Universität Chemnitz (2012); https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279845036_Dynamische_Rissausbreitung_in_Elastomerwerkstoffen |

| [5] | Bathias, C., LeGorja, K., Lu, C., Menabeuf, L.: Fatigue Crack Growth Damage in Elastomeric Materials. Fatigue and Fracture Mechanics: 27th Volume, ASTM STP 1296, R. S. Piascik, J. C. Newman, Dowling, N. E. (Eds.) American Society for Testing and Materials (1997) 505–513 |

| [6] | Rivlin, R. S., Thomas, A. G.: Rupture of Rubber. I. Characteristic Energy for Tearing. J. Polym. Sci. 10 (1953) 291–318 |

| [7] | Bhowmick, A. K., Gent A. N., Pulford, C. T. R.: Tear Strength of Elastomers under Threshold Conditions. Rubb. Chem. Techn. 56 (1983) 226 |

| [8] | Choudhury, N. R., Bhowmick, A. K.: Strength of Thermoplastic Elastomers from Rubber-polyolefin Blends. J. Mater. Sci. 25 (1990) 161–167 |

| [9] | Fukahori, Y., Sakulkaew, K., Busfield, J. J. C.: Elastic-viscous Transition in Tear Fracture of Rubbers. Polymer 54 (2013) 1905–1915 |

| [10] | Tsunoda, K., Busfield, J. J. C., Davies, C. K. L., Thomas, A. G.: Effect of Materials Variables on the Tear Behaviour of a Non-crystallising Elastomer. J. Mat. Sci. 35 (2000) 5187–5198 |

| [11] | Horst, T.: Spezifische Ansätze zur bruchmechanischen Charakterisierung von Elastomeren, Dissertation, Technische Universität Dresden (2011) (ISBN 978-3-942710-33-6; see AMK-Library under K 11) |

| [12] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. 3rd Edition, Carl Hanser Munich (2022) (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [13] | Standard Draft ESIS TC 4 (2001): A Testing Protocol for Conducting J‐Crack Growth Resistance Curve Tests on Plastics |

| [14] | Blumenauer, H.; Pusch, G., Technische Bruchmechanik. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig, Stuttgart (1993), (ISBN 3-342-00659-5; siehe AMK-Library under E 29-3) |

| [15] | Anderson, T. L.: Fracture Mechanics – Fundamentals and Application. 3rd Ed., CRC Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton Ann Arbor London Tokyo (2005) (ISBN 978-0-8493-4260-8; see AMK-Library unter E 8-2) |

| [16] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Deformation and Fracture Behaviour of Polymers. Springer Berlin Heidelberg (2001), (ISBN 978-3-540-41247-2; see AMK-Library under A 7) |