Crack Model according to GRIFFITH

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

GRIFFITH Crack model

Basics of the model

The basic concept of fracture mechanics starts from the analysis of the mechanical behaviour of a single crack in a linear elastic, homogeneous and isotropic continuum. To evaluate the stability of a body with such a macroscopic crack, a continuum mechanical crack model is required that largely ignores the real processes in microscopic regions [1–3].

The best known crack model was introduced into the literature by Griffith [4]. This crack model forms the basis for the description of linear elastic material behaviour based on an energy balance of unstable crack propagation.

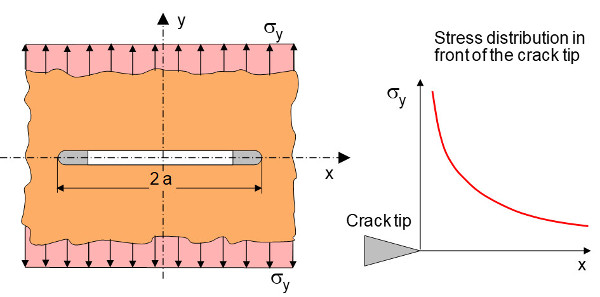

The crack model developed by GRIFFITH assumes a long and narrow crack of length 2a in a disk of infinite extension under tensile stress. The spatial extension of this crack model leads to the so-called "penny-shaped crack".

| Fig. 1: | Crack model according to Griffith [3] |

Derivation of the SNEDDON-WILLIAMS-Equations

In deriving the basic relations of fracture mechanics, it is also possible to start from the calculation of the two-dimensional stress distribution in the region of a crack, carried out with the help of complex analytical functions [6]. The following equations for the magnitude of the stress components in the immediate vicinity of the crack tip were given by Sneddon [5, 7].

Assuming a sharp crack (notch radius r = 0), one obtains for the stresses in the x-y plane:

the SNEDDON-WILLIAMS equations or WILLIAMS-IRWIN equations.

These equations have no validity for r = 0, since they would then lead to the physically nonsensical result of an infinitely high stress

Depending on the specimen thickness B, different multiaxial stress states are formed in front of the crack tip.

Plane Strain and Plane Stress

The two limiting cases of elasticity theory are:

– large specimen thickness → plane strain, σz not equal to 0, i.e. no transverse strains occur in the z-direction

– small specimen thicknesses → plane stress is characterized by the condition σz = 0

(with increasing specimen thickness, the deformation restraint increases !).

For the case of plane strain, σz is therefore not equal to 0 and the normal stress component σz still occurs as a result of the deformation restraint in the z-direction, i.e. parallel to the crack front.

with ν – Poisson's constant.

Importance

The special importance of the SNEDDON-WILLIAMS equations lies in the proportionality to the so-called stress factor or stress intensity factor.

Irwin [8] introduced in 1952 the stress intensity factor

which is a quantity independent of the spatial coordinates (r, Θ) and describes the intensity of the stress field in front of the crack tip and can thus be used to describe the stress on the material. Physically, the stress intensity factor can be interpreted as the intensity of the stress increase in the linear elastic stress field.

Thus, the SNEDDON-WILLIAMS equations are:

The fact that each component and test specimen has a finite geometry is taken into account by introducing a geometry factor f (a/W). IRWIN's equation is thus given the shape:

The geometry function f (a/W) is about 1 for very small crack lengths and infinitely extended specimens.

See also

- Fracture mechanics

- Crack models

- Crack model according to BARENBLATT

- Crack model according to DUGDALE

- Crack model according to IRWIN and Mc CLINTOCK

References

| [1] | Blumenauer, H., Pusch, G.: Technische Bruchmechanik. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig Stuttgart (1982) p. 20 (see AMK-Library under E 29-1) |

| [2] | Blumenauer, H., Pusch, G.: Technische Bruchmechanik. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig (1987) 2. Edition, p. 20 (ISBN 3-342-00096-1; see AMK-Library under E 29-2) |

| [3] | Blumenauer, H., Pusch, G.: Technische Bruchmechanik. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig Stuttgart (1993) 3. Edition, p. 17 (ISBN 3-342-00659-5; see AMK-Library under E 29-3) |

| [4] | Griffith, A. A.: The Phenomena of Rupture and Flow in Solids. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical or Physical Character, Vol. 221 (1921) 163 – 198, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.1921.0006 |

| [5] | Blumenauer, H., Pusch, G.: Bruchmechanik – Grundlagen, Prüfmethoden, Anwendungsgebiete. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig (1973) p. 41 (see AMK-Library under E 28) |

| [6] | Westergaard, H. M.: Bearing Pressures and Cracks. J. Appl. Mech. 6 (1939) Nr. 2, 49–53, https://imechanica.org/files/1939%20westergaard%20bearing%20pressure%20and%20cracks.pdf |

| [7] | Sneddon, J. N.: The Distribution of Stress in the Neighbourhood of a Crack in an Elastic Solid. Proc. Roy. Soc. London A 187 (1946) 229, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1946.0077 |

| [8] | Irwin, G. R.: Fracture. In: Handbuch der Physik, Bd. VI, Flügge, S. (Ed.), Springer Verlag, Berlin (1958) p. 551 |