ICIT – Types of Impact Load–Deflection Diagrams

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

ICIT – Types of impact load–deflection diagrams

Basic types of impact load–deflection diagrams

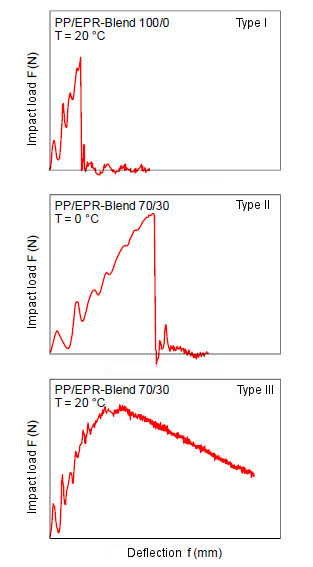

The types of registration diagrams that occur in the instrumented Charpy impact test (ICIT) can be divided into the three basic types shown in Fig. 1 [1‒5].

| Fig. 1: | Typical impact load–deflection diagrams from the instrumented Charpy impact test |

The characteristic measured variables shown in Fig. 1 are used to evaluate the diagrams in the fracture mechanical testing:

| Fmax | – | maximum impact load; force at which a significant drop in force occurs due to the onset of unstable crack propagation, without an increase in deflection |

| Fgy | – | Impact load at the transition from elastic to elastic-plastic material behaviour |

| fmax | – | deflection occurring at load Fmax |

| fgy | – | deflection occurring at load Fgy and |

| FR | – | load at which the unstable crack significantly reduces its velocity or is absorbed by the material (crack arrest) |

| FF | – | Fracture load after previous stable crack propagation. |

The dominant evaluation method problem is the determination of Fgy and fgy, whereby the calculated deformation energies

| AG | – | Total deformation energy, results from the area under the load–deflection diagram up to Fmax |

| Ael | – | eastic part of the deformation energy AG of the test specimen and |

| Apl | – | Plastic part of the deformation energy AG of the test specimen |

can be decisively influenced.

The crack propagation behaviour is also strongly influenced by modification with inorganic and organic fillers and reinforcing materials, which is reflected in the crack propagation energy AR. According to Fig. 1, the shapes of the impact load (F)–deflection (f) diagrams can basically be divided into:

| Typ I | – | represents elastic material behaviour |

| Typ II | – | represents elastic–plastic material behaviour |

| Typ III | – | pronounced stable crack propagation. |

These three basic types can be expanded to types Ia to IIIa if the unstable crack slows down further or is arrested by the material (crack arrest).

Table 1 summarizes the diagram types, the dominant material behaviour, and the selection of fracture mechanics concepts for determining material-specific parameters.

| Diagram type | Material behaviour | FM concept | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Elastic material behaviour | LEFM-concept | Higher specimen thickness; high vH; T < Tg; low molecular weight PP; PS; PA fibre composites |

| Type II | elastic–plastic material behaviour | EPFM-concept | Low specimen thickness; low vH; T > Tg; high molecular weight PP; copolymers; impact-modified plastics |

| Type III | Predominantly stable material behaviour | Crack resistance concept | Low specimen thickness; low vH; higher temperatures; high molecular weight PP; copolymers; elastomer-modified plastics; polymer blends |

| Type Ia, IIa, IIIa | The unstable crack is reduced in speed or comes to a stop. | depending on dominant material behaviour |

Material examples for registering typical impact load–deflection diagrams in the ICIT

Example 1: EPR-modified polypropylene materials (abbreviation: PP/EPR) [6]

The impact load–deflection diagrams of EPR-modified polypropylene materials, recorded in the instrumented Charpy impact test for different temperatures, all showed the three typical diagram shapes (Fig. 2).

The Type I and Type II registration diagrams show the characteristic instability at the maximum load, which is characterised by a steep drop in load and unstable crack growth.

Type III shows a slow load decline after reaching the maximum load, combined with high crack propagation energy AR; the total deformation energy AG up to the maximum load Fmax can be divided into an elastic part Ael and a plastic part Apl.

| Fig. 2: | Typical impact load–deflection diagrams for toughened PP materials [6] |

For type III diagrams, fmax is the deflection at the point of maximum load Fmax; this diagram form requires the determination of crack resistance (R) curves (R curves), from which the characteristic values for describing stable crack initiation and crack propagation are determined.

For materials that show Type III diagrams under the test conditions, it is necessary to determine instability characteristics using alternative methods.

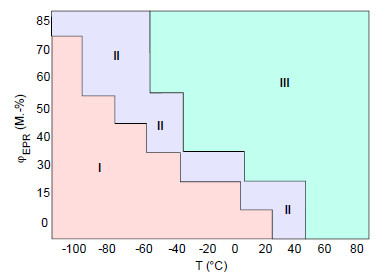

Depending on the mixing ratio of the EPR-modified PP materials and depending on the temperature, the diagram shapes of the F‒f diagrams change in a typical manner (Fig. 3).

Since the shape of the F–f curves also depends on the test specimen geometry, the individual diagram types only represent a qualitative description of the mechanical material parameters. It is not possible to specify characteristic brittle-tough transition temperatures here. This is only possible using geometry-independent fracture mechanical material properties (see also: geometry function and geometry criterion).

| Fig. 3: | Diagram types occurring in toughened PP materials (PP/EPR blends) depending on the mixing ratio and temperature [6] |

Figure 3 shows that

- For low test temperatures and/or low rubber content, linear-elastic material behavior with unstable crack propagation occurs in accordance with diagram type I.

- In a relatively small transition range, elastic–plastic material behaviour with unstable crack propagation (type II) can be observed.

- For high rubber content and/or high test temperatures, the crack propagation behaviour is stable with incomplete material separation (type III) under the selected test conditions.

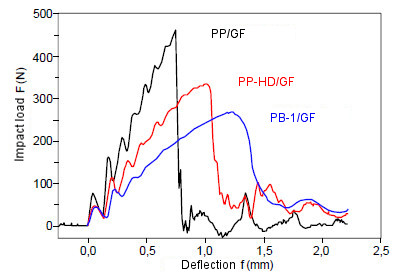

Example 2: Recording of F–f diagrams for glass fiber-reinforced polyolefins

The investigations were carried out on short glass fiber-reinforced polyolefin materials [7]:

- PP + 20 % GF,

- PE-HD + 20 % GF,

- PB-1 + 20 % GF.

| Fig. 4: | Impact load (F)–deflection (f) diagrams of selected glass fiber-reinforced polyolefin materials |

| PP/GF | linear-elastic material behaviour | Type I |

| PE-HD/GF | elastic–plastic material behaviour | Type II |

| PB-1/GF | elastic‒plastic material behaviour with crack propagation energy | Type IIa -> IIIa |

| material | Thoughness values | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| KId (MPa mm1/2) | JId (N/mm) | δId (10-3 mm) | |

| PP/GF | 170 | 7.8 | 142 |

| PE-HD/GF | 127 | 9.2 | 182 |

| PB1/GF | 98 | 9.0 | 225 |

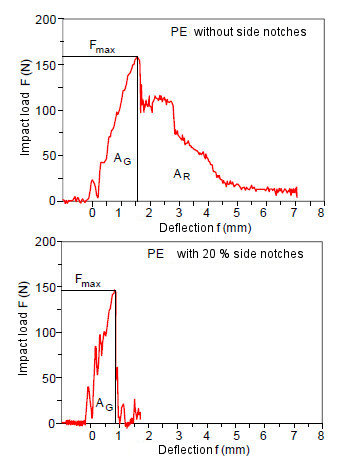

Example 3: Use of side notches to determine fracture mechanics material properties for PE-HD materials [8]

Side notches are used in fracture mechanics testing on highly ductile materials to ensure a flat fracture surface and to minimise the plane stress state in the test specimen, which is reflected in the shear lips and the reduction in thickness at the edge of the test specimen.

| Fig. 5: | Typical impact load‒deflection diagrams for PE on three-point bending specimens without and with 20 % side notching [8] |

The ESIS TC 4 test protocol [9] suggests side notches to achieve a straight crack front of stable crack growth for easier measurement when the differences in crack length exceed 30 %.

The side notches should have a flank angle of 45 ± 5° and a notch radius of 0.25 mm ± 0.05 mm; the total thickness reduction must not exceed 20 % of the specimen thickness; the side notches should not be too sharp to prevent the crack from initiating from the outside rather than from the centre of the test specimen.

Side notches can be made, for example, using a notch device from Instron/Ceast based on the planing principle (see also: Notch insertion).

When calculating fracture mechanical material values, the reduced specimen thickness Bn must be used instead of the specimen thickness.

The occurrence of crack propagation energies always carries the risk of overestimating the material behaviour, as this amount of energy is included in the conventional notch impact strength.

Example 4: Typical impact load–deflection behaviour of chalk-filled thermoplastic composites in ICIT

A key objective in the development of composite materials is to achieve optimum adhesion between the matrix and the additive (e.g. chalk). For this reason, modifying the surface of the additives or fillers is considered to be very important.

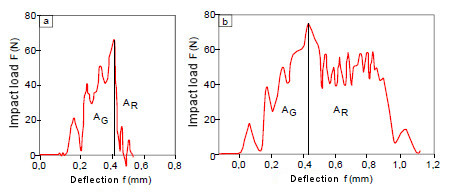

| Fig. 6: | Impact load (F)–deflection (f) diagrams for PE-HD+Omyalite (a) and PE-HD+Omyalite+stearic acid (b) |

The use of surface-modified additives prevents the dominant unstable crack propagation and instead leads to the formation of crack propagation energies.

If the crack propagation behaviour leads to signal shapes as shown in the right-hand section, the transition to parameter determination with stable crack growth must be made due to the predominantly stable crack progression, i.e. the application of the crack resistance (R) curve concept for recording crack resistance curves (see: crack resistance curve – experimental methods) is then required.

See also

- Fracture mechanics

- Deformation

- ICIT – Experimental conditions

- ICIT– Nonlinear material behaviour

- Instrumented Charpy impact test (ICIT)

References

| [1] | Grellmann, W.: Beurteilung der Zähigkeitseigenschaften von Polymerwerkstoffen durch bruchmechanische Kennwerte. Habilitation (1986), Technische Hochschule Merseburg, Wiss. Zeitschrift TH Merseburg 28 (1986), H. 6, pp. 787–788 (Inhaltsverzeichnis, Kurzfassung) |

| [2] | ISO 179-2 (2020-05): Plastics ‒ Determination of Charpy Impact Test ‒ Part 2: Instrumented Impact Test |

| [3] | MPK-Procedure MPK-ICIT (2016-10): Testing of Plastics ‒ Instrumented Charpy Impact Test (ICIT): Procedure for Determining the Crack Resistance Behaviour Using the Instrumented Impact Test |

| [4] | Grellmann, W., Langer, B.: Methods for Polymer Diagnostics for the Automotive Industry. Materialprüfung 55 (2013) 17–22 Download as pdf |

| [5] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Hrsg.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, p. 250 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [6] | Kotter, I.: Morphologie-Zähigkeits-Korrelationen von EPR-modifizierten Polymerwerkstoffen. Mensch Buch Berlin (2003), Dissertation Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg (ISBN 978-3-898206440; see AMK-Library under B 1-11) |

| [7] | Schoßig, M.: Schädigungsmechanismen in faserverstärkten Kunststoffen – Quasistatische und dynamische Untersuchungen. Vieweg + Teubner, Springer Fachmedien, 1st Edition (2011) (ISBN 978-3-8348-1483-89; see AMK-Library under B 1-21) |

| [8] | Beerbaum, H.: Ermittlung strukturbezogener bruchmechanischer Werkstoffkenngrößen an Polyethylenwerkstoffen. Dissertation Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 1999 (ISBN 978-3-898201124; see AMK-Library under B 1-9) |

| [9] | ESIS TC 4 (2001): A Testing Protocol for Conducting J-Crack Growth Resistance Curve Test on Plastics |