Hole Formation Plastics

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Hole formation plastics and sponge or foam structures

General information

The failure of plastic components is usually initiated by microscopic crack formation processes, which cause a macroscopic fracture surface after the ultimate fracture. Depending on the material behaviour of the plastics, the fracture is preceded by stable crack propagation, which ultimately ends in unstable crack propagation with energy release, also known as burst fracture [1, 2].

In the damage analysis of the causes of failure, it is essential to determine the location of crack initiation and the direction of crack propagation in order to gain insights into the damage progression and the stress parameters [3].

Microscopic analysis of the resulting fracture surfaces can provide further information about the type and level of stress, the influence of temperature and media, the test speed, ageing effects and processing errors.

The main objective of damage analysis is therefore to determine the location of crack initiation, the fracture path and its direction of propagation, as well as the crack propagation speed, the type of fracture (ductile or brittle) and possible brittle fracture promoting factors.

The VDI 3822 guideline – Failure Analysis of Plastics – [4] summarises and classifies the characteristic failure features visible on plastic fracture surfaces. However, only a few specific features provide information about the direction of crack propagation and the location of crack initiation. These are the so-called fracture parabolas or hyperbola, also known as U- or V-ramps, and the ramps, clods and steps, which are used as synonymous terms in VDI 3822 [4–6]. Such information cannot normally be derived from the fracture surface features of tips, films and threads, nor from the formation of.

Hole formation and sponge or foam structures

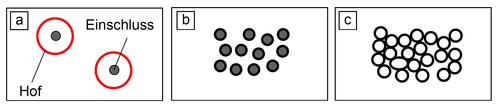

The fracture characteristics of hole formation and sponge or foam structures develop in particular depending on the prevailing stress state, i.e. also the component thickness (see also: geometry criterion), and are frequently observed in multiphase or filled plastics, for example, although the type of plastic (amorphous or semi-crystalline) also has a significant influence [5]. In the VDI 3822 guideline, these fracture surface characteristics (see types of fracture) are characterised by the following symbols (Figure 1) [4].

| FIg. 1: | Schematic representation of (a) holes with inclusions, (b) pores or holes, and (c) sponge or foam structures [4] |

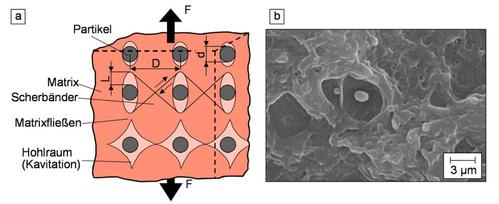

Holes or cavitations (Fig. 1a) tend to occur in filled plastics with ductile material behaviour. The particles can be organic (ethylene propylene diene rubber (abbreviation: EPDM), ethylene propylene rubber (EPR)) or inorganic (talc, glass beads). The expansion of the cavitations that occur depends largely on the volume content and the particle size or diameter d. This results in an average particle spacing D with a homogeneous dispersion of the particles, which in turn influences the so-called cavitation length L under stress (Fig. 2a). With increasing quasi-static or impact loading, increasing shear stress develops in the material (see: shear band formation), which initially leads to isolated holes (Fig. 2b) and then to large-area cavitations, which are also referred to as local deformation with a halo around the inclusion.

| Fig. 2: | Schematic representation of (a) the formation of holes and (b) hole formation with inclusion in a notched tensile test specimen made of polyethylene (abbreviation: PE) at 23 °C [4] |

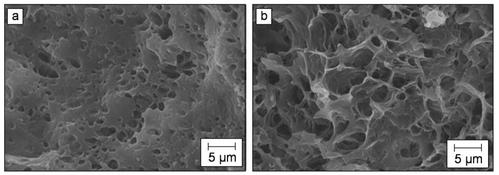

Pores or small holes, which can also occur as fields, arise during processing or as a result of mechanical stress. If the granulate is damp or the melt is not degassed properly, gases can form as a result of the processing temperature. Due to volume expansion, especially in the case of large wall thicknesses or jumps, these gases can lead to holes or cavities in the centre of the component (Fig. 1b) (see: gas bubbles). Mechanical stress, especially in the case of multiaxial stress states and heterophasic plastics, can also lead to large areas of pores or holes, although their local extent is smaller than in the case of cavities (Fig. 3a).

| Fig. 3: | Fracture surface of a polypropylene/EPR blend with (a) pores or holes under impact loading at 23 °C and (b) sponge structure on the cryogenic fracture surface (crack arrest and N2 cooling) of the polypropylene/EPR blend [4] |

Foam or sponge structures can also occur in triaxial stress states and multiphase plastics, but only in the case of very large plastic deformations (Fig. 3b). In this case, tips may also form at the edges of the foam structure, but their dimensions are significantly smaller than those of ramps. Compared to the hole structures, the geometry of the sponges or foams is much more irregular and has open and closed cell structures.

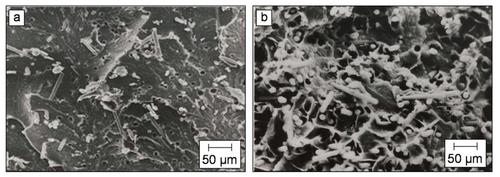

These fracture characteristics should not be confused with the holes in short glass fibre reinforced plastics that occur during the pull-out of glass fibres (Fig. 4).

| Fig. 4: | Fracture surfaces of (a) polyamide 6 (abbreviation: PA 6) with 10 wt.-% GF and (b) polyamide 66 (abbreviation: PA 66) with 20 wt.-% GF under quasi-static tensile stress [7] |

Another example of the damage phenomenon known as hole formation is presented in the article ‘Hole formation films’, where damage begins on the surface of a biopolymer film (see: bio-plastics) [8].

See also

Further information on the pull-out of glass fibres in polymeric or duromeric matrix materials can be found in the following articles:

- Fibre–matrix adhesion

- Equivalent energy concept – Application limits

- Fracture behaviour

- Fibre-reinforced plastics fracture model

- Hybrid methods, examples

- In-situ tensile test in ESEM with AE

- Ultrasound testing

References

| [1] | Grellmann, W.: Beurteilung der Zähigkeitseigenschaften von Polymerwerkstoffen durch bruchmechanische Kennwerte. Habilitation (1986), Technische Hochschule Merseburg, Wiss. Zeitschrift TH Merseburg 28 (1986), H 6, pp. 787–788 (Inhaltsverzeichnis, Kurzfassung) |

| [2] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Deformation and Fracture Behaviour of Polymers. Springer, Berlin (1200), (ISBN 3-540-41247-6; see AMK-Library under A 6) |

| [3] | Kotter, I., Grellmann, W.: Die Fraktografie als Hilfsmittel in der Schadensanalyse an Kunststoffprodukten. 24. Internationale Fachtagung Technomer an der Technischen Universität Chemnitz, (2015), Proceedings V 8.6 |

| [4] | VDI 3822 Blatt 2.1.4 (2024-06): Failure Analysis – Defects of Thermoplastic Products Made of Plastics Caused by Mechanical Stress |

| [5] | Ehrenstein, G. W.: Schadensanalyse an Kunststoff-Formteilen. VDI-Verlag Düsseldorf, (1981), (ISBN 3-18-404068-2; see AMK-Library under D 3) |

| [6] | Ehrenstein, G. W., Engel, K., Klingele, H., Schaper, H.: Scanning Electron Microscopy of Plastics Failure / REM von Kunststoffschäden. Carl Hanser, Munich (2011), (ISBN 978-3-446-42242-1; see AMK-Library under D 5) |

| [7] | Worch, J.: Thermische und akustische Emission kurzfaserverstärkter Thermoplaste. Diploma thesis, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Merseburg, (1995), (see AMK-Library under D 3-84) |

| [8] | Monami, A., Langer, B., Grellmann, W.: Moderne Methoden der Kunststoffprüfung zur Werkstoffentwicklung und Bauteilprüfung/Modern Methods of Polymer Testing for Material Development and Testing of Components. Werkstoffprüfung 2016, Fortschritte in der Werkstoffprüfung für Forschung und Praxis 1. and 2.12.2016, Neu-Ulm, Proceedings pp. 119–124 (ISBN 978-3-514-00830-4) |