Tensile Test Uniform Elongation

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Tensile test uniform elongation (elongation without necking)

Uniform elongation and necking

In ductile materials with a yield point, a distinction is made between the global deformation areas ‘uniform elongation’ and ‘necking elongation’.

Uniform strain is characterised, assuming a plane stress state in the test specimen, by the fact that the longitudinal strain occurring under uniaxial loading in the tensile test is proportional to the resulting transverse strain. If local necking occurs as a result of reaching the yield point or the tensile strength, the cross-section decreases disproportionately and the area of necking deformation begins, whereby this effect is associated with different deformation ranges in metals and plastics.

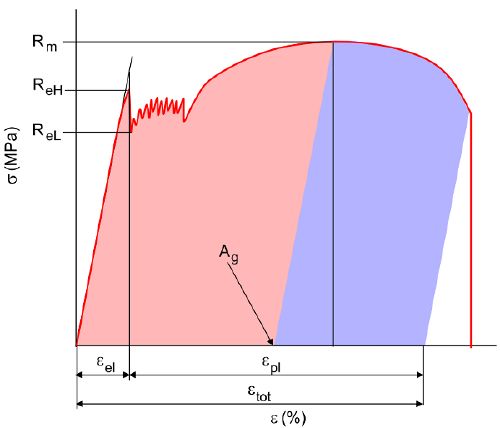

| Fig. 1: | Deformation areas in ductile steels ((red = uniform strain (elongation without necking), blue = necking elongation)) |

In the case of carbonaceous ferritic-pearlitic construction steel, a local stress maximum occurs after the linear-elastic and non-linear-elastic deformation range, which is also referred to as the upper yield strength ReH. This parameter marks the beginning of plastic deformation and is followed by a spontaneous decrease in force or stress. The subsequent singularities in the stress–strain behaviour are characterised by dislocation movements (Lüders lines) and the minimum corresponds to the lower yield strength ReL. As a result of work hardening, the σ–ε curve rises to its maximum, the tensile strength Rm. At this point, the tensile test specimen begins to neck down with a strong localisation of the shear strain. This distinct position is quantified using the parameter AG as the difference between the plastic elongation Lpm and the initial gauge length L0, relative to L0 according to Eq. (1), and is therefore identical to the plastic strain εm:

| (1) |

Deformation behaviour using polyamide 6 as an example

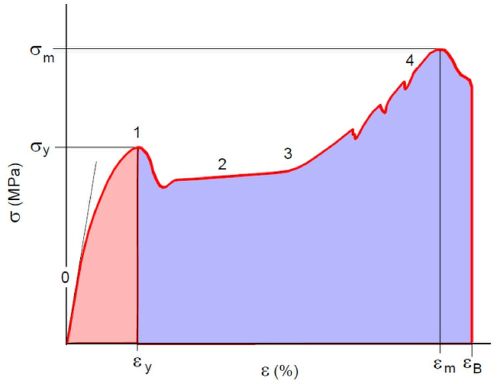

In the case of a ductile polymer material such as polyamide 6 (abbreviation: PA 6), a local stress maximum also occurs after the linear-elastic, linear-viscoelastic and non-linear-viscoelastic deformation, which is also referred to as the yield strength σy (Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2: | Deformation areas in ductile plastics ((red = uniform elongation (elongation without necking)), blue = necking elongation)) |

This yield strength σy marks the beginning of plastic deformation and is accompanied by a spontaneous decrease in force or stress. Up to the yield point, uniform strain dominates due to the proportionality of longitudinal and transverse strain. This is followed by the so-called cold flow region, which is characterised by an increase in macromolecule orientation and a simultaneous decrease in entropy.

Formation of necking

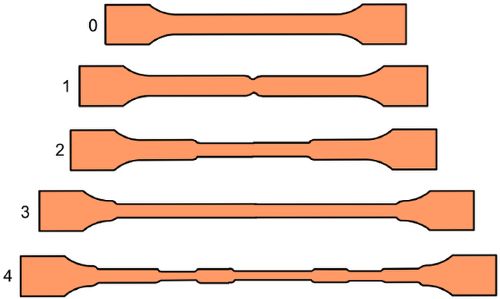

Macroscopically, this process is recognisable by the formation of two necking fronts, which move towards the shoulders of the test specimen as deformation increases (Fig. 3). Due to the localisation of the strain fronts and the simultaneous disproportionate reduction in cross-section, this area is also referred to as necking strain. The increasing orientation in the already stretched areas is also reflected in an increase in density. If, under the given test conditions, the necking fronts reach the shoulders of the test specimen, the hardening zone begins, which is associated with an increase in stress. If the orientation potential is not yet exhausted, especially at low test speeds, further partial yield points may occur (Fig. 2), which manifest themselves in new cross-sectional reductions (Fig. 3).

| Fig. 3: | Deformation phases of a ductile plastic (see Fig. 2) |

This effect only occurs at low strain rates close to the equilibrium state, as this allows sufficient time for the material to respond to the external stress with rearrangement and orientation processes. At high test speeds, a brittle fracture with very low strain at break occurs due to a lack of relaxation conditions.

See also

- Tensile test event-related interpretation

- Tensile test true stress–strain diagram

- Laser cross-unit

- Peripheral fibre strain

References

- Bierögel, C.: Tensile Tests on Polymers. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, pp. 106–123 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-806-5; see AMK-Library under A 22)