Fibre-reinforced Plastics Fracture Model

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Fibre-reinforced plastics fracture model

Models for describing the mechanical deformation and crack propagation behaviour of fibre-reinforced plastics [1]

Theoretical models for calculating the mechanical behaviour of composite materials based on the properties of the components have been used since the beginning of research into this group of materials to predict composite properties, but also to illustrate the physical relationships. These models are known and tested for various parameters and material systems [2–4]. One of the first models, developed by Halpin and Tsai [2], described the elastic modulus of the composite as a function of the fibre content φV and the characteristic composite parameters modulus ratio EF/EM and aspect ratio of the fibres lF/dF.

Lauke, Schultrich and Pompe [3, 5] have presented a comprehensive model for calculating fracture mechanical parameters for glass fibre-reinforced plastics, which has been successfully used to estimate parameters for unstable crack growth in PE and PP glass fibre composites [6] and crack resistance curves for PA66 carbon fibre composites [7]. In both cases, the models were used under the assumption of relative matrix brittle fracture, which can also be observed in dry PA6 at room temperature [7]. In this case, for example, the J-value can be estimated using the J-integral concept and the corresponding J-integral evaluation methods with Eq. (1). This characteristic value is a function of the fibre volume content φV and the average fibre length l. Due to the main failure mechanisms of debonding, sliding, pull-out and brittle fracture of matrix bridges, the corresponding volume-specific energies are also included in Eq. (1).

| (1) |

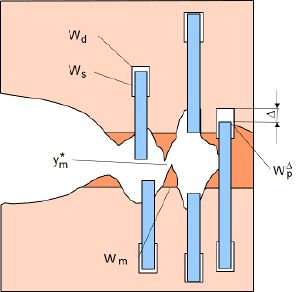

If, on the other hand, the polymer matrix exhibits highly ductile behaviour, the deformation behaviour of the composite changes and energy dissipation occurs mainly through the mechanisms shown in Figure 1. In short glass fibre-reinforced materials, fibre fracture occurs only to a limited extent because the fibre lengths are generally shorter than lc. The critical fibre length lc is the length of the fibre at which more energy would be required for debonding and sliding than for fibre breakage. Energy contributions due to fibre breakage can therefore generally be neglected in short glass fibre-reinforced plastics. Instead of matrix brittle fracture, local flow processes occur in the process zone with global ductile behaviour. Depending on the properties of the fibre-matrix system, there are various possible compositions of the fracture energy WG. If all the mechanisms shown in Figure 1 occur, the fracture energy is the sum of all fracture surface-specific energy contributions according to Eq. (2).

| (2) |

| Fig. 1: | Types of failure of polymer-fibre composites in ductile matrix fracture according to Lauke et al. [3]; energy dissipation through: debonding (Wd), sliding (Ws), plastic deformation of the matrix bridges (Wm), reduced pull-out (WpΔ) and matrix fracture |

The dependence of the mechanisms on the fibre content

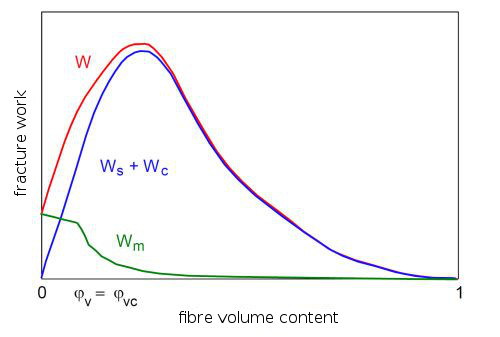

Every energy dissipation mechanism is subject to a certain dependence on the fibre content. These relationships are shown in Figure 2, which also includes the resulting sum curve WG. The energy Wm dissipated during crack growth due to plastic matrix deformation decreases with increasing fibre content φV because the proportion of the polymer matrix involved in the deformation process also decreases by a factor of (1–φV) [3]. The functional dependence of Wm on φV exhibits a discontinuity at φV = φVc. Up to this fibre content, macroscopic plastic flow occurs depending on the test specimen thickness and the stress conditions. The characteristic composite parameter φVc depends on the aspect ratio and is calculated from Eq. (3). Above φVc, the dissipated energy for plastic matrix deformation decreases exponentially.

| (3) |

The energy dissipated by debonding Wd and sliding Ws of fibres in the matrix passes through a maximum. This is induced by the fact that at low amplification levels, the increasing number of energy-dissipative active fibre ends dominates, while at higher amplification levels, the length of the detached and sliding fibre ends decreases more than can be compensated for energetically by their number [3]. The specific lengths ld and ls responsible for energy dissipation through debonding (detachment of the fibres and especially the fibre ends from the matrix) and sliding (sliding of the fibres in the matrix) are functions of the fibre volume content φV. They are also influenced by material properties of the fibre and the matrix, such as the moduli of elasticity EF and EM, the poisson`s ratio (transverse contraction coefficients) of the fibre νF and matrix νM, the coefficient of sliding friction μ and the physically and chemically induced shear stress τs between the fibre and the matrix. The length of the fibre detachment is thus formed in the energy equilibrium between the stresses acting along the fibre in the direction of stress and the normal stresses occurring at the fibre–matrix interface (see: fibre–matrix adhesion). These result from different transverse contractions of the fibre and matrix, as well as friction and adhesive forces.

The dependence of the fracture energy on the fibre content

The maximum fracture energy shown in Figure 2 can also be interpreted as meaning that the energy dissipation occurring at the fibre ends due to debonding and sliding increases until the distance between adjacent fibre ends is no longer sufficient for independent deformation processes. In general, this corresponds to the experimental observations of a decreasing process zone (see: fracture process zone) with increasing fibre content [8] and thus decreasing energy contributions from plastic deformation processes in the dissipation zone [9].

| Fig. 2: | Fracture energy depending on fibre content under dynamic loading (according to Lauke et al. [3]) |

See also

- Fracture behaviour

- Fibre-reinforced plastics

- Fibre–matrix adhesion

- Composite materials testing

- Short-fibre reinforced plastics

References

| [1] | Kroll, M.: Hybride PA 6-Werkstoffe – Methoden der bruchmechanischen Zähigkeitscharakterisierung und Eigenschaftsprofil in Abhängigkeit von den Verarbeitungsbedingungen und der Werkstoffzusammensetzung. Dissertation, MLU Halle-Wittenberg (2013), ISBN 978-3-8440-2335-0, Shaker Publishing Aachen (see AMK-Library under B 1-25) |

| [2] | Halpin, J. C., Tsai, S. W.: Environmental Factors in Composite Materials Design. AFML TR (1967) pp. 67–423 |

| [3] | Lauke, B., Schultrich, B., Pompe, W.: Theoretical Considerations of Toughness of Short-fibre Reinforced Thermoplastics. Wissenschaftliche Berichte 40, Zentralinstitut für Festkörperphysik und Werkstoffforschung, Dresden (1989) |

| [4] | Aykol, M., Isitman, N. A., Firlar, E., Kaynak, C.: Strength of Short Fiber Reinforced Polymers: Effect of Fiber Length Distribution. Polym. Compos. 29 (2008) 6, pp. 644–648 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.20480 |

| [5] | Lauke, B., Friedrich, K.: Fracture Toughness Modelling of Fiber Reinforced Composites by Crack Resistance Curves. Adv. Compos. Mater 2 (1992) 4, pp. 261–275 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/156855192X00080 |

| [6] | Seidler, S., Grellmann, W.: Zähigkeit von teilchengefüllten und kurzglasfaserverstärkten Polymerwerkstoffen. VDI-Fortschr.-Ber., VDI-Reihe 18 Nr. 92, VDI Publishing, Düsseldorf (1991) (ISBN 3-18-149218-3; see AMK-Library under A 4) |

| [7] | Langer, B.: Bruchmechanische Bewertung von Polyamid-Werkstoffen. Dissertation, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg (1997), Logos Verlag; (ISBN 3-897-22063-6; see AMK-Library under B 1-5) |

| [8] | Gomina, M., Pinot, L., Moreau, R., Nakache, E.: Fracture Behaviour of Short Glass Fibre-reinforced Rubber-toughened Nylon Composites. Fracture of Polymers, Composites and Adhesives II Volume 32 (2003) pp. 399–418 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1566-1369(03)80112-7 |

| [9] | Laura, D. M., Keskkula, H., Barlow, J. W., Paul, D. R.: Effect of Glass Fiber and Maleated Ethylene-propylene Rubber Content on the Impact Fracture Parameters of Nylon 6. Polymer 42 (2001) 14, 6161–6172 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861%2800%2900049-5 |

![{\displaystyle J_{c}={\frac {2\gamma _{m}^{0}(1-\varphi _{V})}{1-2\beta E_{c}\left[{\frac {\eta _{d}}{(\sigma _{c}^{d})^{2}}}+{\frac {\eta _{s}}{(\sigma _{c}^{s})^{2}}}\right]-{\frac {\varphi _{V}\tau _{p}l}{2\sigma _{c}^{d}d}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1570fd3d83cb9b641fbaf1746e76a83742985f61)