Craze-Types

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Craze-types or deformation types (Author: Prof. Dr. G. H. Michler)

Introduction

In contrast to a crack, a craze contains highly oriented plastically stretched material. The micromechanical formation mechanism is referred to as crazing or craze mechanism and is closely associated with failure due to fracture. However, the formation of crazes also has positive effects with regard to material behaviour in that the crazes participate in load-bearing due to the stretching of the polymer material and thus increase the toughness. The understanding of the formation mechanisms of the crazes requires a stronger penetration of materials science, whereby the understanding of the structures down to the atomic level with the methods of electron microscopy plays a decisive role. For the important field of mechanical properties, this requires the use of micro- or nanomechanical methods. With their help, nanostructured polymers with improved properties can be obtained. Some of the possibilities for improving plastics are discussed in this article [1–3]:

Crazes, craze-like processes and shear bands

- Crazes are local plastic processes that are concentrated in localized, band-like zones and precede the crack or fracture. They are a general phenomenon and occur not only in polymers but also in various other materials.

- Inorganic glasses are typical examples of amorphous, brittle materials in which fractures propagate very quickly, often abruptly (see also crack propagation). Before the crack tip, however, they reveal small plastic zones in electron microscopic examinations [4].

- Amorphous metals (or metallic glasses) form in some metal alloys during extremely rapid cooling from the melt. Under tensile stress, they show local plastic zones of up to 50 µm in length and up to 1 µm in thickness [5].

- In metals, crack formation and propagation is sometimes associated with the formation of micro-holes and plastically stretched fibrils between the holes, which is reminiscent of coarse crack structures.

- In terms of morphology, bone is a nanocomposite with a brittle fracture behaviour. Especially in the crack tip area, the crack edges are spanned by fibrils of collagen with hydroxyapatite crystals and appear similar to craze-like structures.

- Drying mud, starch slurry or cooling lava builds up shrinkage stresses that lead to a macroscopic crack pattern. As drying continues, shrinkage stresses build up, first creating thicker cracks with wider spacing and then progressively thinner and smaller cracks [6]. The cracks in lava sometimes arrange themselves in regular, hexagonal patterns during the hardening process and then appear in columnar form.

Crazes were first extensively studied in amorphous polymers. The macroscopic appearance similar to cracks led to the name craze. The Anglo-Saxon term “craze” goes back to various Middle English forms, all of which have the meaning of “to break”. The hairline cracks (craquelure) in the glaze of pottery or porcelain still refer to this old meaning (the modern word “crazy” probably also refers to the origin “crazy” in the head). With this meaning, the term “craze” only describes the phenomenological side, but is not accurate in terms of the substance [3]. Crazes are not cracks, but sharply localized deformation zones in micro-areas. Due to the structure of the crazes, they are involved in load-bearing and thus delay rapid, brittle crack propagation.

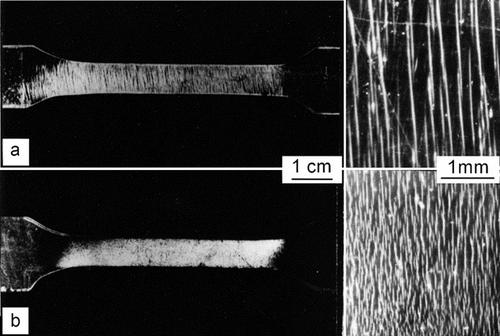

The exact knowledge of the structure of crazes is mainly based on electron microscopic examinations and also on X-ray scattering measurements. Crazes are best known from amorphous, brittle polymers such as polystyrene ( abbreviation: PS), polymethyl methacrylate ( abbreviation: PMMA) and many others. An overview of crack patterns in PS and PMMA rods is shown in Fig. 1 and the typical fibrillar internal structure can be seen in Fig. 2.

| Fig. 1: | Multipurpose test specimens with crazes after loading until shortly before fracture in general view (left) and in low light-optical magnifications from the rod centers (right) a) Polystyrene (PS) |

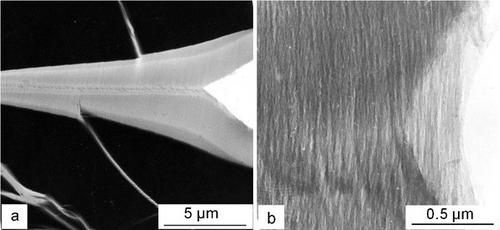

Crack propagation in the crazes occurs by successive overstressing and tearing of the crack fibrils (Fig. 2). There is a continuous reproduction of the stress concentration at the crack tip in the crack, and since the crazes are often very long, rapid, brittle crack propagation occurs without a tendency to crack tip rounding.

| Fig. 2: | Crack propagation in a craze in polystyrene with successive stretching, overspanning and tearing of the craze fibrils a) Overview |

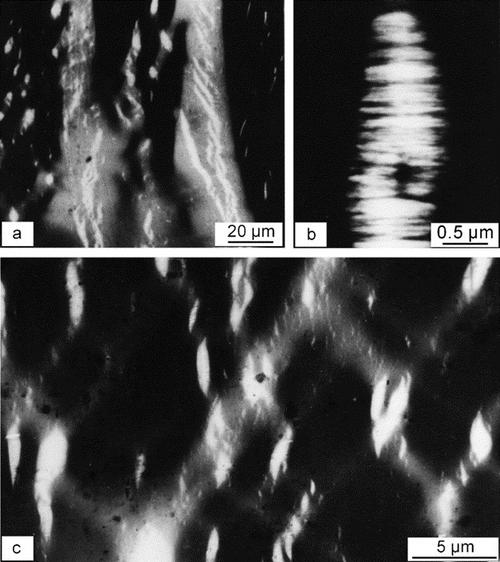

In addition to crazes with fibrils (craze type I), some polymers also contain crazes without fibrillation, i.e. with a homogeneous internal structure (craze type II). Both types I and II of crazes are also found together with shear bands – a coexistence of all three types of deformation zones is demonstrated in Figure 3 in a polyvinyl chloride material ( abbreviation: PVC). The occurrence of these deformation zones is also linked to the entanglement network and the entanglement density. With increasing entanglement density (decreasing entanglement molecular weight and decreasing distance), the coexistence of fibrillated and homogeneous crazes occurs with a transition to homogeneous crazes and shear bands [7, 8].

| Fig. 3: | Coexistence of isolated, fibrillated crazes I (Fig. 3b), of fibrillated crazes II in a homogeneous deformation zone (Fig. 3a), and shear bands between crack tip and crazes (Fig. 3c) in a PVC, deformed thin section in the HEM, strain direction |

Influence of particles on deformation mechanisms

Initiated deformation mechanisms

Particles can influence the fracture process and thus the mechanical properties in a variety of ways [9]. Larger particles or larger defects can be detached from the environment before the propagating main crack, and thus generate a secondary crack. When the secondary crack is overlapped with the propagating crack, parabolic patterns are created with the defect as the (mathematical) focal point of the parabola.

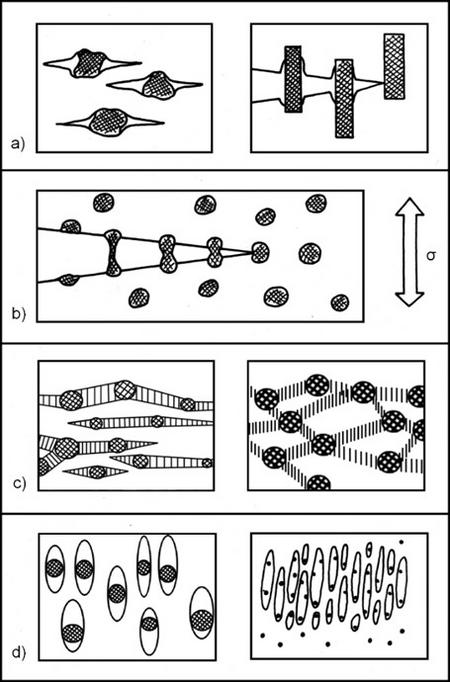

However, defects or particles in a matrix can also initiate ductile mechanisms instead of a brittle fracture. Fig. 4 illustrates various cases of deformation mechanisms that can be initiated by different particle-like structures:

a) Multiple hole initiation and microcrack formation: Detachment of particles or fibres generate new surfaces and microcracks. Large defects initiate secondary cracks.

b) Bridging mechanism: If ductile, softer particles are present that are well bonded to the matrix (good interfacial adhesion), they can span the banks of cracks that have formed and delay crack propagation. A further advantage is the effect that crack tips can be stopped at the soft particles (crack stopping mechanism – Fig. 5).

c) Multiple initiation of plastic deformation: Ductile, soft particles as in b) act as stress concentrators in a harder matrix and initiate local flow processes in the equatorial zones or between the particles (shear deformations or, in glassy polymers, flow zones, the crazes).

d) Nano-hole formation with fibrillations: If particles in the size range of sub-µm are present, localized flow up to fibrillation can be initiated in a ductile material with low interfacial adhesion between particles and matrix after detachment, micro-hole formation and stress concentration in the adjacent matrix regions. The prerequisite for this is that the sub-µm particles only have a narrow particle size distribution (i.e. are approximately the same size) and are homogeneously distributed. Large particles and spatially inhomogeneously distributed particles lead more to case a).

| Fig. 4: | Various local mechanisms initiated by particles or particulate structures a) Hole formation and multiple crack formation |

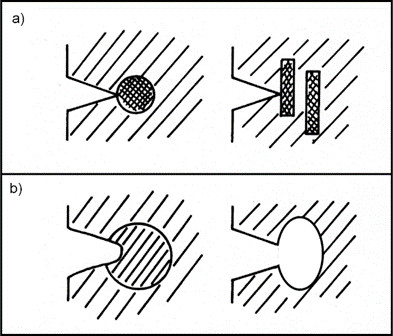

However, particles in a matrix can also hinder or stop the propagation of cracks – Fig. 5. Crack stopping or reduction of the crack propagation speed can be achieved by:

a) Impact of a crack in an area of higher strength, for example on hard particles or stiff fibres

b) Penetration of a crack into a particle of higher ductility, or also into a cavity (micro-hole). Rounding the crack tip (crack tip blunting; see crack resistance curve – Experimental methods) significantly reduces the stress concentration (see fracture mechanics) at the crack tip.

| Fig. 5: | Crack arrest mechanisms – load direction vertical a) Crack arrest on softer particles or micro-cavities due to crack blunting |

Stress concentrations on particles

As mentioned in Fig. 5c, particles or general particulate inhomogeneities play a role in the deformation behaviour of all materials, as they cause local stress concentrations. An externally applied load generates stress concentrations in an elastic body in the environment of a particle, especially in the zones perpendicular to the load direction (equarial zones). The stress component σδδ, which acts parallel to the particle/matrix interface in the surrounding matrix, is of special importance. The stress component σδδ for a soft particle in an elastic environment reaches almost twice the applied stress directly at the equator (δ = 90°) (stress analyses according to Goodier [10]). Towards the poles (δ = 0°), the stress decreases and changes from a tensile stress to a compressive stress (σδδ < 0). The difference in the particle modulus GP relative to the matrix modulus GM (GP/GM) also has an influence. The maximum stress concentration σδδ occurs when soft particles (small particle modulus GP) are present in a harder matrix.

If many softer particles are present in the matrix at a close distance A, the stress fields of the individual particles overlap. The stress concentrations are essential for the introduction of deformation zones and thus the increase in toughness.

See also

- Micromechanics & Nanomechanics

- Fracture mechanics

- Fracture types

- Crack propagation

- Crack opening

- Crack resistance curve – Experimental methods

References

| [1] | Michler, G. H.: Werkstoffwissenschaft und Kunststoffe. Schriften der Sudetendeutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften und Künste. Band 43, Forschungsbeiträge der Naturwissenschaftlichen Klasse, Munich (2024) 27–58; see AMK-Library under F 33 |

| [2] | Michler, G. H.: Mechanik – Mikromechanik – Nanomechanik. Vom Eigenschaftsverstehen zur Eigenschaftsverbesserung. SpringerSpektrum (2024); ISBN 978-3-662-66965-5; e-book: ISBN978-3-66966-2; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-66966-2; see AMK-Library under F 34 |

| [3] | Michler, G. H.: Kunststoff-Mikromechanik: Morphologie, Deformations- und Bruchmechanismen. Carl Hanser Munich (1992); ISBN 3-446-17068-5; see AMK-Library under F 4 |

| [4] | Hopfe, J., Albrecht, R., Hillebrandt, R., Pippel, A., Schmidt, V.: HREM investigation of highly strained inorganic glasses of different compositions. Ultramicroscopy 15, 71–80 (1984); https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3991(84)90076-7 |

| [5] | Takayama, S., Maddin, R.: Fracture of amorphous Ni-Pd-P alloys.

Philos. Mag. 32 (1975) 457–470; https://doi.org/10.1080/14786437508219968 |

| [6] | Müller, G.: Physikalische Blätter Nr.10, 55, 35–37 (1999) |

| [7] | Berger, L. L.; Kramer, E. J.: Microdeformation in partially compatible blends of poly(styrene-acrylonitrile) and polycarbonate. J. Mater. Sci. 22, 2739–2750 (1987); https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01086466 |

| [8] | Kramer, E. J.: Craze fibril formation and breakdown. Polym. Eng. Sci. 24, 761–769 (1984); https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.760241006 |

| [9] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Deformation and Fracture Behaviour of Polymers. Springer Berlin Heidelberg (2001); ISBN 978-3-540-41247-2; see AMK-Library under A 7 |

| [10] | Goodier, I. N.: Concentration of stress around spherical and cylindrical inclusions and flaws. J. Appl. Mech. Trans. ASME 55 (1933) 39–44 |

Weblinks

- Wikipedia – The Free Encyclopedia: Crazing: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crazing

- Michler, G. H.: Modellierung des Einflusses des Kautschukgehaltes auf die Craze-Bildung in schlagzähen Polymeren. Acta Polymerica Vol. 36, Issue 6 (1985)325–330; https://doi.org/10.1002/actp.1985.010360607

- Grellmann, W., Bierögel, C., Reincke, K. (Hrsg.): Crazing. In: Wiki „Lexikon Kunststoffprüfung und Diagnostik“ Version 15.0 (2025), https://wiki.polymerservice-merseburg.de/index.php/Crazing