Fracture Mechanics: Difference between revisions

Oluschinski (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{Language_sel|LANG=ger|ARTIKEL=Bruchmechanik}} {{PSM_Infobox}} <span style="font-size:1.2em;font-weight:bold;">Fracture mechanics</span> __FORCETOC__ ==Linear-elastic fracture mechanics== Fracture mechanics assumes that the fracture of a component and thus of the material occurs as a result of the propagation of cracks. It investigates the conditions for Crack Propagation|crack propaga..." |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 09:27, 2 December 2025

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Fracture mechanics

Linear-elastic fracture mechanics

Fracture mechanics assumes that the fracture of a component and thus of the material occurs as a result of the propagation of cracks. It investigates the conditions for crack propagation and allows quantitative relationships to be established between the external stress, i.e. the nominal stress acting on the component or test specimen, the size and shape of the cracks, and the resistance of the material to crack propagation.

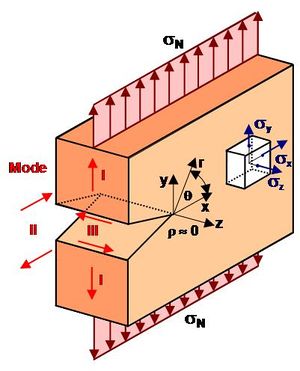

The LEFM concept describes the stress state in the vicinity of the crack tip using the stress intensity factor K (Fig. 1):

| (1) |

with

| ij | normal and/or shear stress | |

| r, | polar coordinates with crack tip as point of origin | |

| gij | dimensional function. |

| Fig. 1: | Coordinate system for describing stress state at crack tip |

The stress intensity factor introduced by IRWIN [1] is given by

| (2) |

with

| N | nominal stress | |

| a | Crack length |

The finite geometry of each component and test specimen, as well as the crack geometry, are taken into account by introducing a geometry function f (a/W), whereby Eq. 2 takes the form

| (3) |

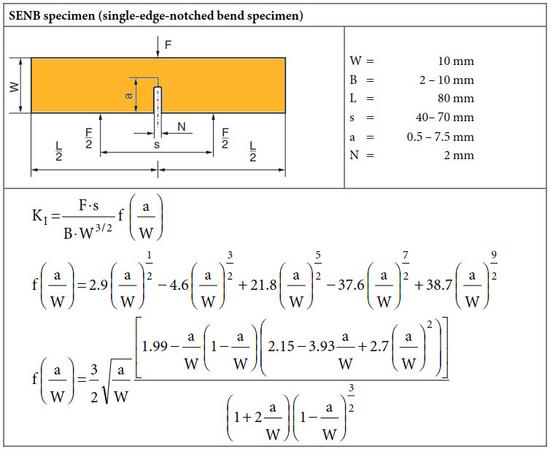

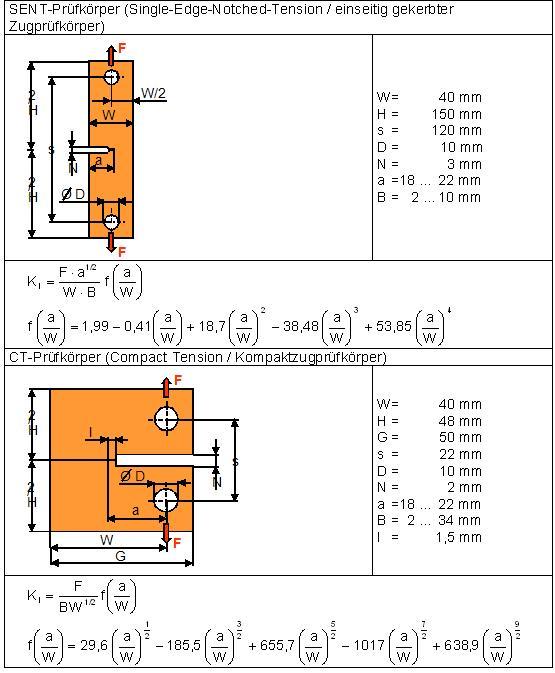

can be written. The functions f (a/W) have been calculated for a large number of fracture mechanics test specimens [2, 3]. Figs. 2 and 3 show the dimensions of test specimens preferably used for plastics. For an infinitely extended test specimen and the limiting case of a crack with a notch radius ρ ~ 0, the geometry function f (a/W) = 1.

At the start of unstable crack propagation, the stress intensity factor reaches a critical value KIc, which is referred to as fracture or crack toughness and is measured in MPa mm1/2. The index I indicates mode I loading, in which the load is applied perpendicular to the crack surface.

| Fig. 2: | Test specimen shape SENB with dimensions, the corresponding equations for calculating the fracture toughness (stress intensity factor) and the geometric functions |

| Fig. 3: | Specimen shapes SENT and CT with their dimensions, the corresponding equations for calculating fracture toughness and the geometric functions |

For the most important technical case of stress, the fracture safety criterion is

| (4) |

according to which the fracture safety of a component is guaranteed as long as the critical value is not exceeded.

In addition to the simple crack opening according to mode I, Figure 1 also shows fracture modes II and III, which occur under shear or torsional stress.

Depending on the test specimen geometry, different multiaxial stress states form in front of the crack tip.

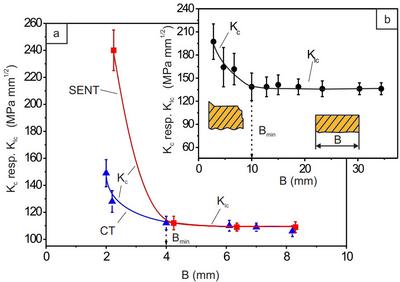

Figure 4 shows the influence of the test specimen thickness on the fracture behaviour using the example of post-chlorinated PVC (abbreviation: PVCC) and polypropylene (abbreviation: PP), whereby a macroscopic increase in normal stress fracture is observed as a result of the transition from the plane stress state to the plane strain state.

If the plane strain state is present at the crack tip, the fracture toughness becomes independent of the test specimen geometry. It reflects the influence of the material structure, the velocity and the ambient temperature on the toughness.

| Fig. 4: | Dependence of fracture toughness Kc, KIc at room temperature on the test specimen thickness under quasi-static stress for PVCC with with KIc = 110 MPamm1/2 (a) and for PP with KIc = 139 MPamm1/2 (b) bei einer crosshead speed of vT = 8,3 • 10-4 ms-1 |

Using a linear-elastic approach, the geometric parameters B, a and the ligament extension (W – a) are estimated using the empirically determined relationship [2, 4–6]

| (5) |

with

| y | yield stress (yield point) |

The geometric constant β is material-dependent [4, 7–10].

References

| [1] | Irwin, G. R.: Analysis of Stress and Strain Near the End of a Crack Traversing a Plate. J. Appl. Mech. 24 (1957) 361 |

| [2] | Anderson, T. L.: Fracture Mechanics. Fundamentals and Applications. 2nd Ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton (1995) (ISBN 978-0849342608; see AMK-Library under E 8-1) |

| [3] | Tada, H., Paris, P. C.; Irwin, G. R.: The Stress Analysis of Cracks Handbook. 3th Ed., ASME Press, New York (2000) (ISBN 0791801535) |

| [4] | Blumenauer, H., Pusch, G.: Technische Bruchmechanik. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig Stuttgart (1993) (ISBN 3-342-00659-5; see AMK-Library under E 29-3) |

| [5] | Francois, D., Pineau, A. (Eds.): From Charpy to Present Impact Testing. ESIS Publication 30, Elsevier Science Ldt. Oxford (2002) (ISBN 9780080439709) |

| [6] | Akay, M.: Fracture Mechanics Properties. In: Brown, R. (Ed.): Handbook of Polymer Testing. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York (1999) (ISBN 1-85957-324-X) pp. 533–588 |

| [7] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S., Hesse, W.: Prozedur zur Ermittlung des Risswiderstandsverhaltens mit dem instrumentierten Kerbschlagbiegeversuch. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S.: Deformation und Bruchverhalten von Kunststoffen. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg (1998) S. 75–90, (ISBN 3-540-63671-4; e-Book (2014): ISBN 978-3-642-58766-5; see AMK-Library under A 6) |

| [8] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Deformation and Fracture Behaviour of Polymers. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg (2001) (ISBN 978-3540412472; see AMK-Library under A 7) |

| [9] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S., Lach, R.: Geometrieunabhängige bruchmechanische Werkstoffkenngrößen – Voraussetzung für die Zähigkeitscharakterisierung von Kunststoffen. Material und Werkstofftechnik 32 (2001) 552–561 |

| [10] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S.: Determination of Geometry Independent Fracture Mechanics Values of Polymers. Int. J. of Fracture 68 (1994) R19–R22 |

Linear-elastic fracture mechanics with small-scale yielding

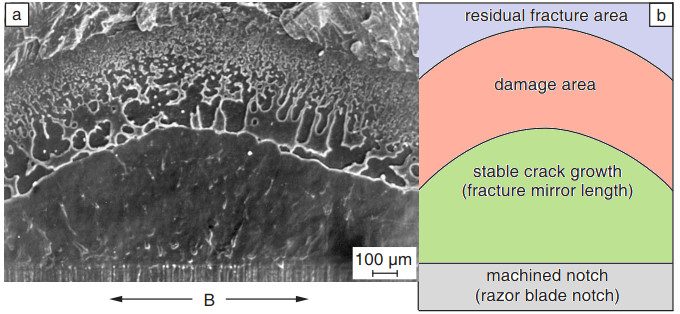

By taking into account the fracture mirror aBS when describing toughness (Fig. 5), whereby the initial crack length a must be extended by the microscopically measured length of stable crack growth,

| (6) |

the transition to LEFM with small-scale yielding is formally completed. The length of the fracture mirror, which is predominantly determined experimentally using light microscopy, is the measured variable for the radius of the plastic zone, which is introduced into fracture mechanics in the crack model according to IRWIN and Mc CLINTOCK. The sum of the length of the initial crack (notch length) and the fracture mirror is referred to as the effective crack length. In very brittle structures (gross spherulitic) and at high loading speed or low temperatures, the fracture mirror is negligible.

| Fig. 5: | Fracture surface of an ethylene-propylene random copolymer with 4 mol.-% etyhylene (a) and schematic diagram of characteristic areas (b) |

Elastic–plastic fracture mechanics (EPFM)

In the case of macroscopically brittle fracture of a component, the critical error size is often caused by stable crack growth of existing incipient cracks. Of particular technical significance here are crack enlargement due to mechanical stress (static, dynamic, oscillating) and medial stress (stress cracking corrosion).

If the expansion of the plastic zone (see also: ‘effective crack length’) is not small in relation to the component or specimen dimensions, the fracture is preceded by plastic flow in larger areas of the material in front of the crack tip. Since this case occurs in most structural materials under normal operating conditions, linear-elastic fracture mechanics has been further developed into yield fracture mechanics, i.e. fracture mechanics with general plastic deformation.

The theoretical basis is provided by the DUGDALE crack model derived by Wells in 1961, which is based on the assumption that the fracture process is deformation-determined. The formation of a microstructurally induced plastic zone is permitted. In addition to the Cack Tip Opening Displacement (CTOD) concept based on this assumption, the J-integral concept and the crack resistance (R) curve concept are established as further concepts of elastic–plastic fracture mechanics (EPFM).

In the case of elastic--plastic material behaviour, the fracture process is characterised by the stages of crack blunting (see: crack resistance curve), crack initiation, stable crack propagation and, subsequently, possibly unstable crack propagation. This entire process can be described by the crack resistance curve (R curve) of yield fracture mechanics.

In recent years, considerable progress has been made in determining material science characteristic values using the concepts of yield fracture mechanics, with particular attention being paid to the specific deformation and fracture behaviour of plastics. Methods for structural analysis and methods for explaining deformation mechanisms have made an essential contribution here.

With regard to the applicability of fracture mechanical material parameters in plastics development, particular attention is paid to the quantification of energy-dissipative processes using generalised integral criteria of fracture mechanics. This includes the JTJ-concept developed by Michel and Will in 1986, which enables the quantification of energy-dissipative processes during stable crack growth. The suitability of this concept for establishing quantitative morphology–toughness correlations was demonstrated by Seidler in 1996. Phase distributions, sizes and interactions in polymeric multiphase systems are the focus of interest as morphological variables.

By combining fracture mechanics investigation methods and morphological investigations, taking into account the test temperature, correlations between morphology and crack initiation and propagation behaviour are clarified, which form the basis for quantitative morphology–toughness correlations.

See also

- Fracture mechanical testing

- Fracture

- Levels of knowledge in fracture mechanics

- Crack

- Notch

- Toughness

- Crack toughness

Refereces

- Blumenauer, H., Pusch, G.: Technische Bruchmechanik. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig Stuttgart (2003), 3rd Edition, (ISBN 3-342-00659-5; see AMK-Library under E 29-3)

- Seidler, S.: Anwendung des Risswiderstandskonzeptes zur Ermittlung strukturbezogener bruchmechanischer Werkstoffkenngrößen bei dynamischer Beanspruchung, Habilitation (1997), Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, VDI-Reihe 18: Mechanik/Bruchmechanik Nr. 231, VDI Verlag Düsseldorf (1998) (ISBN 978-3-1832-3118-8; see AMK-Library under B 2-1)

- Anderson, T. L.: Fracture Mechanics; Fundamental and Applications. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2005) (ISBN 978-0849342608; see AMK-Library under E 8-2)

- Krüger, L., Trubitz, P., Hentschel, S.: Bruchmechanisches Verhalten unter quasistatischer und dynamischer Beanspruchung. In: Biermann, H., Krüger, L.: Moderne Methoden der Werkstoffprüfung. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim (2014) pp. 1–52; ISBN 978-3-527-33413-1 (see AMK-Library under M 35)