Deformation

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Deformation

Anisotropic deformation

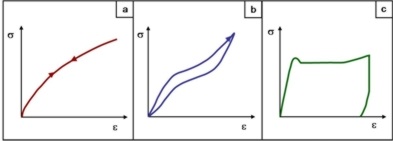

In many plastics, the relationship between stress and strain is nonlinear even at small deformations (Fig. 1a). However, as Fig. 1 shows, there is still proportionality between stress and strain. In this case, unlike most metallic materials, the requirement of linear proportionality is not met.

Another type of nonlinear behaviour is exhibited by rubber or elastomeric materials that are subjected to high strains and then relieved (Fig. 1b). If the unloading curve lies below the loading curve, energy is dissipated during the deformation cycle. This phenomenon is known as hysteresis. However, the term is only applicable if the material returns to zero deformation. If the elastomeric material is filled or reinforced, a permanent displacement occurs, as with other plastics, even if this is below the strain at yield stress, i.e., in the elastic or viscoelastic range.

Ductile plastics often exhibit a well-defined yield stress with elongations at yield stress of 5–10 % (Fig. 1c). This is usually followed by plastic deformation, the absolute amount of which depends significantly on the deformation rate. Depending on the type of plastic, work hardening may also occur.

| Fig. 1: | Schematic representation of anisotropic deformations

a) Nonlinear elastic deformation |

Viscous deformation

In contrast to elastic behaviour, viscous behaviour is characterised by the complete irreversibility of the deformation processes. It follows that:

- Once applied, the deformation remains even after the load is removed; the relationship between stress and strain is only clear when the history is taken into account, but cannot be determined with certainty in reverse.

- The work expended for the deformation is completely dissipated by the material.

In structural terms, viscous behaviour involves a relative displacement of neighbouring structural units (molecules or molecular sequences in polymer materials). The frictional forces to be overcome depend on the deformation velocity. If a linear relationship between stress and deformation rate is observed, NEWTONian material behaviour is present. This is characterised by the viscosity η as a material parameter.

Reference

- Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, pp. 78–79 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22)

Elastic deformation

Elastic deformation is characterised by the fact that the work performed by external forces is stored reversibly as energy of deformation. If there is a linear, instantaneous interaction between force and deformation, then the material behaviour is linear-elastic. In this case, Hooke's law applies (see: energy elasticity), whereby the modulus of elasticity describes the spring constant of the material.

In other words, mechanical behaviour is always described as elastic when there is a reversible, clear relationship between the stress and strain states. It is therefore completely reversible in both a mechanical and thermomechanical sense.

Depending on the different thermodynamic causes, a distinction is made between energy elasticity and entropy elasticity.

Reference

- Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (202) 3rd Edition, pp. 75–77 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22)

Plastic deformation

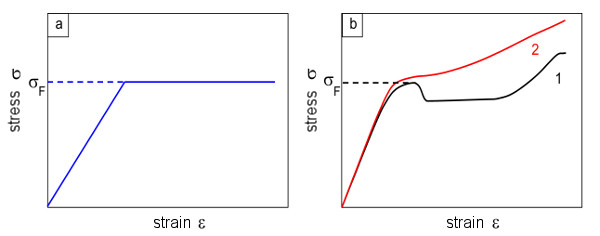

Plastic deformation is a combination of reversible and irreversible processes. In contrast to viscous (viscoelastic) behaviour, however, these do not occur simultaneously, but are separated by a yield point σF. Below this yield point, the material behaviour is elastic or viscoelastic; above it, irreversible flow processes take place (see Fig. 2a) [1].

Plastic deformation behaviour is observed in many amorphous and semi-crystalline plastics. Under uniaxial tensile stress, it manifests itself in the form of a yield stress σs, as shown in Fig. 2b. This is a local maximum in the stress–strain curve, which is usually observed at strains between approximately 5 and 25 %.

| Fig. 2: | Relationship between stress and strain in plastic material behaviour: model (a) and plastic (b) (1: apparent curve; 2: true curve) |

The occurrence of yield stress is related to a local reduction in cross-section on the test specimen, also known as necking. Irreversible deformations of several hundred percent occur in the necking zone. This inhomogeneity results in large differences between the nominal and actual stress or strain. By determining true stress‒strain diagrams, it has been shown that the stress drop after exceeding the yield stress is often only an apparent geometric effect [2].

The level of yield stress required for the onset of plastic flow processes depends on the stress state, the temperature and the loading speed. The influence of the stress state can generally be described by the yield stress hypotheses known from classical mechanics [3]. However, amorphous and semi-crystalline plastics show significant differences with regard to the deformation mechanisms that occur during plastic deformation. In amorphous plastics, plastic deformation takes place in the glass state. Here, local molecular motion processes under the influence of stress cause the formation of plasticised microdomains, whose growth and union lead macroscopically to plastic deformation in the form of shear bands or crazes [4, 5]. In semi-crystalline plastics, plastic deformation generally occurs above the glass transition temperature in the amorphous regions. Here, crystallographic gliding processes represent the decisive deformation step [6‒8], resulting in the transformation of the lamellar initial structure into a fibrillar structure [9, 10]. From the observation of the deformation mechanisms, it becomes clear that the microscopic processes leading to plastic deformation already begin well below the yield point. They can often be detected even at stresses in the linear-viscoelastic range, so that correlations between the relaxation time spectrum and plastic behaviour can be established [11].

Plastic deformation results in the orientation of macromolecules. The associated changes in properties are the goal of numerous processing methods. Molecular orientation causes entropic elastic restoring forces (see entropic elasticity), which counteract plastic deformation and are the cause of the strengthening processes observed during large deformations. A further increase in stress leads to local breakage of overloaded polymer chains, which precedes macroscopic failure or fracture of the material.

See also

- Deformation mechanisms

- Energy elasticity

- Entropy elasticity

- Crazing

- Fracture types

- Tensile test event-related interpretation

- Shearband formation

References

| [1] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, pp. 85–86 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-53; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [2] | G’Sell, C., Jonas, J. J.: Determination of the Plastic Behaviour of Solid Polymers at Constant True Strain Rate. J. Mater. Sci. 14 (1979) 583‒591 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00772717 |

| [3] | Ward, I. M.: Review: The Yield Behavior of Polymers. J. Mater. Sci. 6 (1971) 1397‒1417 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00549685 |

| [4] | Argon, A. S.: A Theory for the Low-temperature Plastic Deformation of Glassy Polymers. Philos. Mag. 28 (1973) 839‒865 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14786437308220987 |

| [5] | Perez, J.: Physics and Mechanics of Amorphous Polymers. A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam (1998) (e-Book ISBN 978-0-2037-4333-1) |

| [6] | Bowden, P. B., Young, R. J.: Deformation Mechanisms in Crystalline Polymers. J. Mater. Sci. 9 (1974) 2034‒2051 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00540553 |

| [7] | Lin, L., Argon, A. S.: Structure and Plastic Deformation of Polyethylene. J. Mater. Sci. 29 (1994) 294‒323 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01162485 |

| [8] | Christ, B.: Plastic Deformation of Polymers. In: Thomas, E. I. (Ed.): Materials Science and Technology, Vol. 12: Structure and Properties of Polymers. Wiley VCH, Weinheim (2002) (ISBN 978-3-52726825-2) |

| [9] | Peterlin, A.: Plastic Deformation of Polyethylene by Rolling and Drawing. Kolloid Z. u. Z.: Polymer 233 (1969) 857‒862 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01508005 |

| [10] | Petermann, J., Kluge, W., Gleiter, H.: Electron Microscopic Investigation of the Molecular Mechanism of Plastic Deformation of Polyethylene and Isotactic Polystyrene Crystals. Polym. Sci. B-Polym. Phys. 17 (1979) 1043‒1051 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1979.180170612 |

| [11] | Bauwens-Crowett, C., Bauwens, C. J., Homes, G.: Tensile Yield Stress Behavior of Glassy Polymers. J. Polym. Sci. A-2-Polym. Chem. 7 (1969) 735‒742 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1969.160070411 |