Crack Formation

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Crack formation

The deformation energy for fracture formation

In order to explain the processes involved in fracture formation, it is useful to compare an unloaded tensile test specimen with a loaded tensile test specimen without and with a crack.

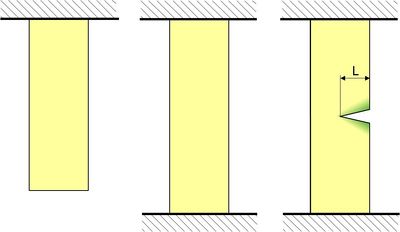

| Fig. 1: | Stretching and cracking in a firmly clamped tensile test specimen. Energy is stored in the material during stretching. A crack in its vicinity (green areas) causes the material to relax and release the stored energy, allowing the crack to spread further. |

In an unloaded state, there is naturally no deformation energy. If we now subject the test specimen to a tensile load σ, the energy σ2/2E is stored per unit volume, and as long as both ends are firmly clamped, this mechanical energy cannot leave the material. Provided there are no defects, the energy is distributed approximately homogeneously over the specimen volume. Now let us assume that there is a crack of length L on one side of the test specimen. On both sides of this slightly gaping crack, the material can relax (green areas in the image) because to load stress can be transferred. During unloading, most of the stored deformation energy is released, which is then available for the fracture mechanism, allowing the crack to propagate.

The free surface energy

The formation of fresh fracture surfaces requires energy whose amount must be at least as great as the free surface energy γ. In fact, the energy requirement can be much higher. Fracture energy W is defined as the total energy required for a new surface to form during tearing over a unit length. The fracture energy for a crack of length L with its two fracture surfaces is therefore 2 WL, i.e. it increases proportionally to the crack length L.

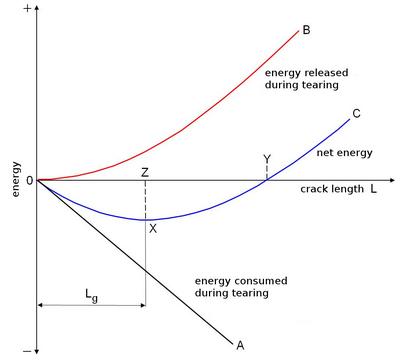

In contrast to the linear increase in fracture energy, the deformation energy released usually increases proportionally to L2. This quadratic increase is reflected by the triangular areas marked in green in Figure 1. If the deformation energy is plotted as a function of crack length, the curve is normally a parabola. The curve for fracture energy and deformation energy can be used to compare the energy requirement and energy release (see: energy release rate) during tearing (see Figure 2).

| Fig. 2: | Energy balance during crack propagation. Once a crack reaches a critical length Lg, further tearing releases more energy than is consumed – the net energy increases |

The energy for crack propagation

Up to point X on the net energy curve, energy is consumed during tearing. Above this point, however, the system releases energy and the crack spreads further on its own. Cracks that are shorter than the critical GRIFFITH length Lg are stable for energetic reasons. Once the critical length is exceeded, cracks become unstable and spread faster and faster as they grow longer.

GRIFFITH's calculations for the critical length Lg are mathematically complicated, but his final result is encouragingly simple:

Using the formulas, Lg can be expressed algebraically:

Here, W denotes the fracture energy required for one square metre (measured in J/m2); E is the modulus of elasticity (in N/m2), Σ is the average tensile strength (without taking stress concentrations into account) in the vicinity of the crack (in N/m2) and Lg is the critical length (in m).

If W is now equated with the surface energy γ of a solid, it can be easily shown mathematically that the approach using forces leads to the same result as the energy argument. For a crack or defect of length L, the same effects result mathematically in both cases. However, GRIFFITH pointed out that even in very brittle materials such as glass, the energy W that must be expended for crack formation is greater than the surface energy γ. This is because tearing not only involves the separation of atomic or molecular bonds, but also disrupts or damages the material structure.

See also

'References

- Gordon, J. E.: Strukturen unter Stress. Mechanische Belastbarkeit in Natur und Technik. Aus dem Amerikanischen übersetzt von Axel Bewersdorf. Spektrum der Wissenschaft, In: Spektrum-Bibliothek Bd. 21, Heidelberg (1987) pp. 90–92 (ISBN 978-3-9225-0894-6) (see AMK-Library under L 33)