Surface Energy

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Surface energy

Basics

Surface energy – often also referred to as so-called surface tension, although not of the Pascal dimension – is a material property. In general, surface energy is defined as the free energy of surfaces at temperatures above absolute zero.

Strictly speaking, however, the term "surface energy" would have to be expanded to include the term "interfacial energy", since the actual surface energy, i.e. the free energy of a liquid or solid surface against a vacuum, is only recorded in very rare cases. Mostly, therefore, relative energy values of the phase boundary of liquids to other liquids or gases/vapours or interfaces of solid substances to other substances that are present as solids (inner interfaces), liquids or gases/vapours are summarised under this term. The interfacial energy is therefore not a material property, but characterises the property of a substance system and is therefore a system property.

The surface or interfacial energy is of essential importance for plastics, especially for varnishes and paints, coatings and adhesives. However, it is also of great interest when it comes to the wettability or non-wettability of plastic surfaces in general. One example from the plastics industry is polyethylene films, which are used to package foodstuffs containing water. With these films, the water from the food can deposit on the inside of the film in the form of small droplets, which is known as fogging. By specifically changing the surface energy, this effect can be suppressed, thus maintaining the transparency of the films.

The specific interfacial energy of solids is often understood as the amount of work that is at least necessary to create new surfaces (e.g. through crack propagation and fracture). This is the basis of the GRIFFITH criterion of fracture mechanics (see crack model according to GRIFFITH). However, it has been shown that these values determined by fracture mechanics (see fracture mechanics testing) are only in the order of magnitude of the values determined by other methods for extremely brittle materials (e.g. Si–Single crystals). Even for brittle plastics and very low temperatures (< -150 °C), the values determined in this way, such as critical J values Jc, are about four to five orders of magnitude greater. For thermoplastics, they cover the range of a few kJ/m2 (for amorphous thermoplastics such as polycarbonate ( Plastics – Symbols and abbreviated terms: PC), polymethyl methacrylate ( Plastics – Symbols and abbreviated terms: PMMA) and polystyrene ( Plastics – Symbols and abbreviated terms: PS), Jc = 1.0...1.8 kJ/m2 [1, 2]). In addition to the (micro)plastic deformation processes (internal energy) occurring in these materials even at very low temperatures, this discrepancy can also be explained by heat toning, i.e. by the generation of heat as a result of internal friction processes during the deformation processes associated with the creation of new surfaces (see: fracture surface). The ideal brittle fracture (see: fracture types), on the other hand, is an athermal process.

Measurement of surface energy

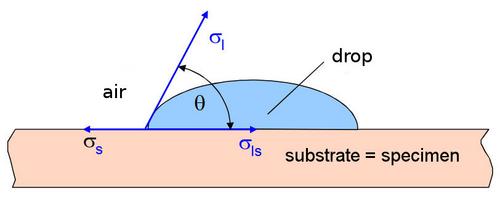

The interfacial energy of a plastic surface against a liquid medium (often water) and mostly air is determined by means of the contact angle measurement (method of the lying drop) (Fig. 1). For this purpose, a well-defined drop of liquid is deposited on a flat and previously thoroughly cleaned plastic surface. The contact angle can then be determined by computer using a special experimental device (for details of the experimental procedure, see e.g. [3]).

| Fig. 1: | Interfacial energies at the three-phase contact: σs – solid surface energy, σl – liquid surface energy, σls – interfacial energy, Θ – rand or contact angle |

The interfacial energy is determined by Young's equation (1) [4], neglecting the influence of the gaseous medium (such as air) (hence σs and σl are referred to here as surface energy).

| (1) |

| with: | ||

| σs | – | solid surface energy (mJ/m2) |

| σl | – | liquid surface energy (mJ/m2) |

| σls | – | interfacial energy (mJ/m2) |

| Θ | – | rand or contact angle (degrees); wettability decreases with increasing angle |

Furthermore, by adding Eq. (1), the work W required per area to detach a droplet from a solid can be calculated according to the YOUNG-DUPRÉ equation (2) [5].

| (2) |

This takes into account that two new interfaces (liquid versus air and solid versus air) are created, while the liquid/solid interface disappears.

On the other hand, Girifalco and Good [6] found that the work of detachment W can be approximately expressed in terms of the geometric mean of the surface energies of liquid and solid (σs and σl) using Eq. (3).

| (3) |

By using different reference fluids, this method can also be used to determine the polar σlsp and the disperse fraction σlsd of the interfacial energy. Here, the polar interactions contributing to the interfacial energy are the KEESOM interaction [7] between two dipoles and the DEBYE interaction [8] between a dipole and a polarisable molecule. The disperse part of the interaction, which contributes to the interfacial energy, arises from the forces due to the London interaction [9] between two polarisable molecules. All three interactions contribute to the van der Waals forces [10].

The two types of interaction (polar and disperse), being independent of each other, now contribute additively to the magnitude of W. Eq. (3) thus yields Eq. (4) (p and d stand for polar and disperse):

| (4) |

This additivity also applies to the surface energies of liquid and solid. With the relationship (5) contained after substitution of Eq. (4) into Eq. (2) and transformation

| (5) |

according to Owens, Wendt, Rabel and Kaelble (OWRK method) [11–13], the polar and disperse (and thus also the total) surface energy of a solid can now be determined. To do this, the contact angle is measured using several liquids with known polar and disperse surface energy. By plotting as function of the polar part of the solid surface energy is obtained as the slope of the resulting straight line and the disperse part as the point of intersection with the y-axis.

Another method used for polymer materials to determine the polar and disperse part of the surface energy is the method according to Wu [14] using equation (6).

| (6) |

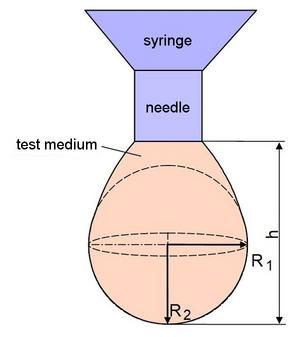

| Fig. 2: | Hanging drop method: R1, R2 – main curvature radii, h – vertical height of the drop |

The hanging drop method is used to determine the surface energy of a plastic melt (or solution) (Fig. 2). Here, the surface energy is determined from the contour of a hanging drop that is dosed by means of a syringe. The shape of the drop forming at the lower end of the dosing needle can be described mathematically exactly (neglecting the influence of the surrounding gas) according to Eq. (7) in accordance with the YOUNG-LAPLACE equation [4, 15] by the equilibrium of forces between gravity and surface energy (for details of the experimental procedure see e.g. [3]):

| (7) |

| with: | ||

| σl | – | liquid surface energy (mJ/m2) |

| R1, R2 | – | main radii of curvature (m) |

| ρ | – | density of the liquid (g/m3) |

| g | – | acceleration due to gravity (m/s2) |

| h | – | vertical height of the drop (m) |

Surface energies of selected polymer materials

Table 1 summarises the surface energy values for selected polymer materials. Typically, these values are in the range of about 20... 50 mJ/m2.

| material | Dispersed part of the surface energy (mJ/m2) | Polar part of the surface energy (mJ/m2) | Total surface energy (mJ/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy resin | 19.5 | 13.2 | 32.7 |

| PA6 | 25.6...39.2 | 5.0...15.4 | 38.3...54.6 |

| PAEK | 36.0 | 3.8 | 39.8 |

| PBT | 39.4...41.8 | 3.3... 9.4 | 43.8...48.8 |

| PC | 27.3...37.0 | 1.8... 6.0 | 33.3...38.8 |

| PE-HD | 30.0...35.0 | 0.0... 0.7 | 30.3...35.7 |

| PE-LD | 33.2...35.1 | 0.0 | 33.2...35.1 |

| PES | 42.1 | 5.1 | 47.2 |

| PET | 32.9...43.2 | 3.1... 4.5 | 37.3...47.3 |

| PFA | 19.1 | 3.4 | 22.5 |

| PMMA | 25.7...44.2 | 4.3...14.6 | 40.2...51.3 |

| POM | 36.0...42.2 | 5.1...11.1 | 42.1...47.9 |

| PP | 25.8...42.1 | 0.3... 1.3 | 31.2...42.4 |

| PPE | 42.7...44.7 | 2.1... 3.2 | 45.9...46.8 |

| PS | 23.3...44.6 | 0.6... 6.9 | 29.0...45.4 |

| PSU | 42.1 | 4.2 | 46.3 |

| PTFE | 18.5...18.6 | 0.0... 0.5 | 18.5...19.1 |

| PVB | 36.0 | 4.7 | 40.7 |

| PVC | 26.0...40.0 | 1.5...12.7 | 37.3...51.7 |

| SAN | 27.1...42.1 | 2.7... 7.7 | 31.1...47.2 |

| TPU | 35.2 | 3.8 | 39.0 |

PA6 – polyamide 6, PAEK – polyaryletherketone, PBT – polybutylene terephthalate, PC – polycarbonate, PE-HD – high-density polyethylene, PE-LD – low-density polyethylene, PES – polyethersulfone, PET – polyethylene terephthalate, PFA – PTFE copolymer, PMMA – polymethyl methacrylate, POM – polyoxymethylene, PP – polypropylene, PPE – polyphenylene ether, PS – polystyrene, PSU – polysulphone, PTFE – polytetrafluoroethylene, PVB – polybutylvinyl butyrate, PVC – polyvinyl chloride, SAN – styrene-acrylonitrile copolymer, TPU – thermoplastic polyurethane. (see Plastics – Plastics – Symbols and abbreviated terms)

If the polar fraction of the surface energy is greater than 1 mJ/m2, we speak of polar plastics, if it is smaller, we speak of non-polar plastics [16].

Plastics with a low surface energy and/or non-polar plastics, which include, for example, polyolefin materials in general, such as polyethylene ( abbreviation: PE) and polypropylene ( abbreviation: PP), as well as plastics based on polytetrafluoroethylene (abbreviation: PTFE) (cf. Table 1), are used for non-stick coatings (PTFE and its copolymers, such as perfluoro-tetrafluoroethylene (PFA)), in the food industry (especially PE) and for pipes and containers (PE and PP). However, due to the low surface energy or the low polar part of the surface energy, they are difficult to print on without special surface pre-treatment.

See also

References

| [1] | Lach, R.: Korrelationen zwischen bruchmechanischen Werkstoffkenngrößen und molekularen Relaxationsprozessen amorpher Polymere. VDI-Fortschritt-Berichte, Reihe 18: Mechanik/Bruchmechanik, Nr. 223, VDI-Verlag, Düsseldorf (1998) (ISBN 3-18-322318-x; see AMK-Library under B 1-7) |

| [2] | Hartwig, G., Saatkamp, T.: Fracture Properties of Polymers at Cryogenic Temperatures. Advances in Cryogenic Engineering 40 (1994) 1121–1127 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9053-5_142 |

| [3] | Kopczynska, A., Ehrenstein, G. W.: Oberflächenspannung von Kunststoffen. Messmethoden am LKT. Sonderdrucke am Lehrstuhl für Kunststofftechnik, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, see https://www.lkt.tf.fau.de/files/2017/06/Oberflaechenspannung.pdf and Kopczynska, A.: Oberflächenspannung. In: Ehrenstein, G. W.: Strukturverhalten. Struktur und Eigenschaften von Kunststoffen, Oberflächenspannung und Spannungsrisse. Carl Hanser Munich (2021), (ISBN 978-3-446-46703-3; see AMK-Library under F 25) |

| [4] | Young, T.: An Essay on the Cohesion of Fluids. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 95 (1805) 65–87 |

| [5] | Dupré, A., Dupré, P.: Théorie Mécanique de la Chaleur. Gauthier-Villars, Paris (1869) |

| [6] | Girifalco, L. A., Good, R. J.: A Theory for the Estimation of Surface and Interfacial Energies. I. Derivation and application to interfacial tension. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 61 (1957) 904–909 https://doi.org/10.1021/j150553a013 |

| [7] | Keesom, W. H.: The Second Virial Coefficient for Rigid Spherical Molecules whose Mutual Attraction is Equivalent to that of a Quadruplet Placed at its Center. Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences 18 (1915) 636–646 |

| [8] | Debye, P.: Polare Molekeln. S. Hirzel Verlag, Leipzig (1929) |

| [9] | London, F.: The General Theory of Molecular Forces. Transactions of the Faraday Society 33 (1937) 8–26 https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/1937/tf/tf937330008b |

| [10] | van der Waals, J. D.: Over de Continuïteit van den Gas- en Vloeistoftoestand. Dissertation, Universität Leiden (1873) |

| [11] | Kaelble, D. H.: Dispersion-polar Surface Tension Properties of Organic Solids. The Journal of Adhesion 2 (1970) 66–81 https://doi.org/10.1080/0021846708544582 |

| [12] | Owens, D., Wendt, R.: Estimation of the Surface Free Energy of Polymers. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 13 (1969) 1741–1747 https://doi.org/10.1002/app.1969.070130815 |

| [13] | Rabel, W.: Einige Aspekte der Benetzungstheorie und ihre Anwendung auf die Untersuchung und Veränderung der Oberflächeneigenschaften von Polymeren. Farbe und Lack 77 (1971) 997–1005 |

| [14] | Wu, S.: Polar and Nonpolar Interactions in Adhesion. The Journal of Adhesion 5 (1973) 39–55 https://doi.org/10.1080/00218467308078437 |

| [15] | Marquis de Laplace, P. S.: Traité de Mécanique Céleste. Courcier, Paris (1805), Vol. 4, Supplément au Dixième Livre du Traité de Mécanique Céleste, 1–79 |

| [16] | Erhard, G.: Konstruieren mit Kunststoffen. 4. Auflage, Carl Hanser Verlag, München (2008), 152–153 (ISBN 978-3-446-41646-8; siehe: AMK-Library under G 33) |