Sound Emission Experimental Conditions: Difference between revisions

Oluschinski (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{Language_sel|LANG=ger|ARTIKEL=Schallemission}} {{PSM_Infobox}} <span style="font-size:1.2em;font-weight:bold;">Sound emission experimental conditions</span> __FORCETOC__ ==General== Sound emission testing is used on plastics to investigate damage behaviour and locate sources of acoustic emissions in components, and in materials testing and development to characterise dominant Deform..." |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 14:31, 5 December 2025

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Sound emission experimental conditions

General

Sound emission testing is used on plastics to investigate damage behaviour and locate sources of acoustic emissions in components, and in materials testing and development to characterise dominant damage mechanisms, to represent the temporal damage kinetics and to determine damage limits, the results of which can be applied constructively in damage mechanics. For this purpose, various evaluation methods of sound emission analysis, such as amplitude, energy or frequency analysis, as well as simple characteristic values (hits, events or impulses) are used to represent damage development [1, 2].

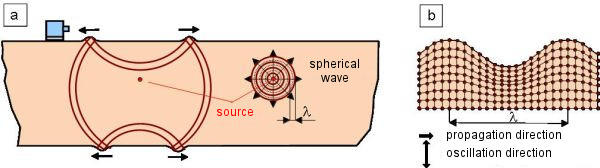

Sound emissions or acoustic emissions always occur in solids when certain critical material stresses are exceeded (microcracks, fibre breaks, delamination and debonding, see: fibre-reinforced plastics fracture model), elastic energy is emitted in the form of mechanical stress waves, which propagate in the test object primarily as spherical volume waves (Fig. 1) [1]. In geometrically limited test objects, a mode conversion then occurs at the surface, which makes it possible to register the acoustic emission by means of surface or Rayleigh waves even at a greater distance from the sound emission source location.

| Fig. 1: | Wave mode conversion in confined test objects (a) and surface wave behaviour (b) |

Frequency response of ultrasonic sensors

However, the propagation of ultrasonic waves in the material (see: ultrasound testing) depends largely on the transmission behaviour of the measuring chain, which consists of the ultrasonic receiver, the preamplifier and main amplifier, and the filters used. As a result, the original signal undergoes numerous changes due to frequency dispersion, reflection and scattering, causing the recorded measurement signal to differ significantly from the source signal. This means that the original square wave pulse becomes a long signal that slowly rises and falls.

Other reasons for changes to the original signal include:

- Material-inherent loss mechanisms

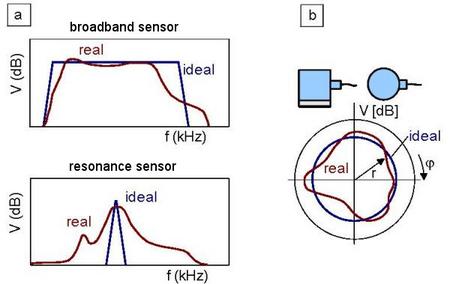

- Sensor influences, especially directional characteristics and frequency (Fig. 2)

- Interference with the useful signal by extraneous noise

- Viscosity, layer thickness and damping behaviour of the coupling medium

- Surface quality of the component or test specimen

- Contact pressure between transducer and surface

| Fig. 2: | Frequency response of different sensors (a) and their directional characteristics (b) |

Distance between the measuring point and the sound source

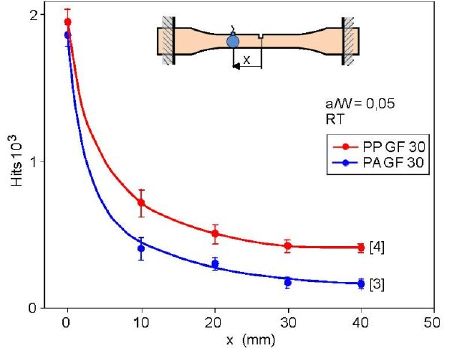

However, the signal received is also significantly influenced by the measurement location and the mass of the sensor in relation to the test specimen [3]. Figure 3 shows the influence of the change in measurement location distance x from a specified predetermined breaking point for polypropylene (abbreviation: PP) and polyamide 6 (abbreviation: PA), each with 30 m.-% short glass fibres.

| Fig. 3: | Dependence of registered hits on measurement distance x |

If the sensor is located directly above the sound source, the maximum number of hits is measured for both materials with notches, which is mainly based on the registered volume waves. As the distance increases, the heat number decreases significantly and approaches an asymptote at x = 30 mm. Since small changes in the exact position near the source location have a greater effect, the scatter of the measured values is significantly higher here. If the sensitivity of the sensor is sufficient, the sensor should therefore always be at a sufficient distance from the known sound source.

Influence of the intrinsic mass of the sound emission sensor

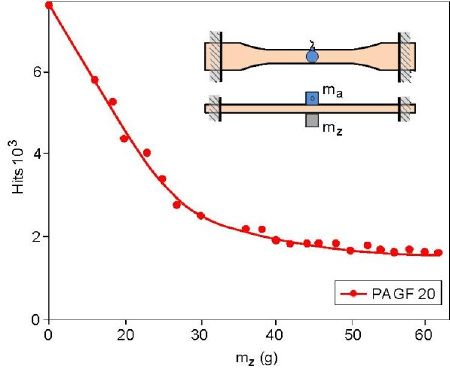

When a BRÜEL&KJAER 8313 resonant acoustic emission sensor with an intrinsic mass of 16 g is positioned centrally, a heat count of approx. 7,500 is recorded for polyamide with 20 m-% short glass fibres until fracture of the test specimen in the tensile test (Fig. 4). By attaching an additional mass mz to the opposite side of the test specimen, the increase in the dead weight of the sensor used is simulated in the tensile tests.

| Fig. 4: | Dependence of registered hits on the mass mz of the sound detector |

It can be seen from Fig. 4 that the mass of the sensor has a significant influence on the result of the sound emission test. Up to an additional mass of 36 g, the hit numbers drop sharply and, with a further increase, result in an almost constant level of hit numbers.

Linear location measurements

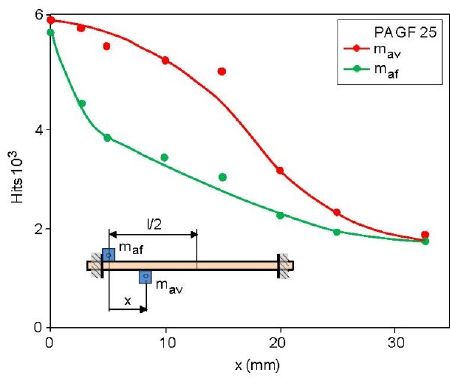

If two identical BRÜEL&KJAER 8313 sensors (pair) are used to measure the acoustic emissions, the result for polyamide with 25 % glass fibres is shown in Fig. 5. One sensor maf is fixed directly near the clamping point, taking into account the injection point, while the location of the other sensor mav is varied up to the centre of the test specimen l/2. It can be seen that comparable hit numbers are only measured in the centre of the test specimen and when both sensors are positioned at the clamping point, which is particularly important to note when performing linear location measurements.

| Fig. 5: | Dependence of registered hits on the position of the sound sensors |

See also

- Acoustic emission

- Sound emission

- Sound emission analysis

- Sound emission testing

- Sound velocity

- Ultrasound birefringence

- Ultrasonic sensors

References

| [1] | Bardenheier, R.: Schallemissionsuntersuchungen an polymeren Verbundwerkstoffen – Part I: Das Schallemissionsmessverfahren als quasi-zerstörungsfreie Werkstoffprüfung. Zeitschrift für Werkstofftechnik 11 (1980) 41–46 |

| [2] | Bohse, J.: Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Micro-Failure Processes in Polymer Blends and Composites. Composites Science and Technology 60 (2000) 1213–1226; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-3538(00)00060-9 |

| [3] | Bierögel, C.: Zur Problematik der Schallemissionsanalyse an verstärkten Thermo- und Duroplasten. Dissertation, Technische Hochschule Leuna-Merseburg (1984) |

| [4] | Wessolek, U.: Untersuchungen zur Berücksichtigung der Dämpfung auf die Ergebnisse der Schallemissionsanalyse bei kurzfaserverstärkten Plasten. Master Thesis, Technische Hochschule Leuna-Merseburg (1981) |