Elastic Modulus: Difference between revisions

Oluschinski (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{Language_sel|LANG=ger|ARTIKEL=Elastizitätsmodul}} {{PSM_Infobox}} <span style="font-size:1.2em;font-weight:bold;">Elastic modulus</span> __FORCETOC__ ==Introduction== In addition to the Poisson's ratio, the modulus of elasticity (modulus ''E'') is also an important parameter for describing the energy-elastic properties (see: energy elasticity) of plastics. The short-term moduli ''E''<sub>t..." |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 09:39, 1 December 2025

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Elastic modulus

Introduction

In addition to the Poisson's ratio, the modulus of elasticity (modulus E) is also an important parameter for describing the energy-elastic properties (see: energy elasticity) of plastics. The short-term moduli Et, Ef and Ec determined in quasi-static tests such as tensile, bending or compression tests are suitable for quality assurance, material development and optimisation, as well as simple dimensioning tasks (see: plastic component), but cannot be used for demanding structural applications. In this case, the creep modulus (see: creep behaviour – determination) from long-term experiments must also be used, depending on the test temperature.

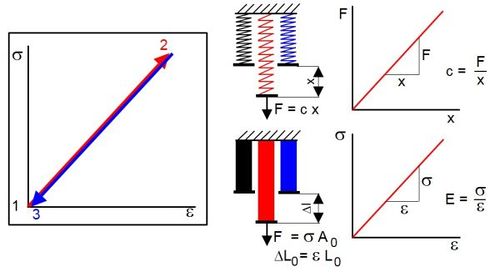

The structural cause of the energy-elastic behaviour of plastics is the change (elongation, compression) in the average atomic distances and bond angles when subjected to mechanical stresses. The mechanical work performed in this process is stored in the form of potential energy (increase in internal energy) and is completely recovered when the stress is removed (1st law of thermodynamics). Due to its structural causes, energy-elastic behaviour is limited to the range of small deformations. The deformation is completely reversible, whereby the relationship between stress and deformation can be linear or non-linear. The loading and unloading curve is identical in every case, which means that no hysteresis occurs. If a linear relationship between stress (force) and strain (see also: deformation) is observed, then in the case of a uniaxial tensile or compressive load, the relationship can be clearly described by HOOKE's law (Eq. 1) in analogy to a spring or proportionality constant (Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1: | Elastic deformation of the spring model and the solid body according to HOOKE |

Energy elasticity dominates the behaviour of polymer materials, particularly in the case of small deformations and at low temperatures, as well as at high deformation rates (see also: strain rate basics), whereby classical energy elasticity theory contributes significantly to understanding the deformation behaviour of plastics. In addition, it provides useful approximate solutions for the quantitative description of the stress–strain relationship (see also: true stress–strain diagram) in this area, at least for uniaxial normal stress [1].

In testing practice, three methods are mainly used to determine the modulus of elasticity. These are quasi-static tests for polymer testing, dynamic mechanical analysis and ultrasonic testing, with short-term mechanical tests (see: tensile test) being the most relevant in practice.

Test methods for determining the modulus of elasticity

Quasi-static short-term tests

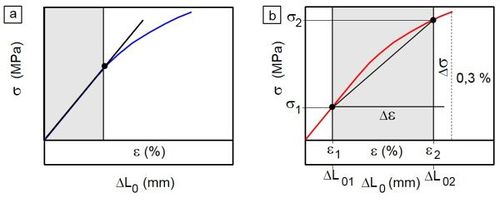

To determine the modulus of elasticity E, tensile, bending and compression tests are performed in quasi-static polymer testing using a universal testing machine. In contrast to the testing of metallic materials (see also: materials testing), where the modulus of elasticity (also known as Young's modulus) is determined as the tangent modulus at the origin of the stress–strain diagram, the secant modulus is determined in standard-compliant testing of plastics. The reason for this lies in the comparatively low elastic deformation range of < 0.1 % elongation and in the linear-viscoelastic behaviour, which is recorded up to approximately 0.3 %. The reversible strain range up to 0.3 %, although time-dependent, is followed by the range of non-linear viscoelasticity, in which the first irreversible micro-damage and deformations occur. For this reason, the strain limits in the three specified test methods [2–4] were specified as 0.05 and 0.25 %, and the corresponding stress values are determined in the test (Fig. 2). To avoid run-up effects in, for example, tensile tests, an offset of 0.05 % is set or a preload is specified that causes this strain value. The test, which is carried out at an elongation rate of approximately 1 %/min, is stopped above 0.3 % or is continued at a test speed of, for example, 50 mm/min as a tensile test until the test specimen fails [6]. The elasticity moduli Et, Ef or Ec are calculated uniformly according to Eq. (1), using the strain in the tensile test ε, the peripheral fibre strain in the bending test εf or the compression in the compression test εc as specified values.

| Fig. 2: | Determination of the tangent modulus for metals (a) and the secant modulus for plastics (b) |

| (1) |

If necessary, these tests can also be carried out in a temperature-controlled chamber, allowing the modulus of elasticity to be represented as a function of temperature.

Dynamic-mechanical analysis (DMA)

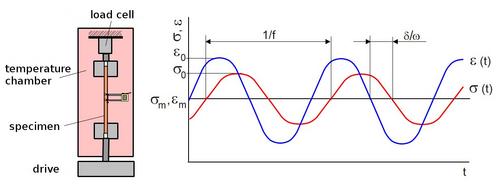

In dynamic-mechanical analysis or spectroscopy, the test specimen is subjected to periodically alternating, mostly sinusoidal stress. The advantage of this method when using a temperature control chamber (dynamic-mechanical thermal analysis – DMTA) is that the dynamic-mechanical characteristics are available as a function of temperature (Fig. 3). By varying the frequency, it is also possible to characterise the time dependence of the material behaviour. Dynamic mechanical analysis can be performed with free damped vibrations (pendulum vibrations) or in forced vibration and resonance mode. The types of stress torsion, bending and tension are commonly used. What all methods have in common is that the deformation of the test specimen is very small and should not exceed the linear-viscoelastic range. As a result of these small deformations, DMA or DMTA can be used to achieve high test frequencies with mechanical excitation up to 200 Hz in a temperature range from approx. –180 °C to 400 °C [1, 7].

| Fig. 3: | DMTA system Eplexor from NETSCH Instruments GmbH, Ahlen |

For polymer testing using DMA or DMTA under tensile stress [8], small hydraulic, pneumatic or electrodynamic testing machines and DMTA systems with additional equipment such as strain sensors and temperature control chambers (Fig. 3) are primarily used to generate sinusoidal strains or stresses. The testing system then applies a constant sinusoidal strain or stress amplitude with a defined and constant frequency to the test specimen, whereby in plastics testing, the tensile threshold range is preferred due to the specimen geometry. The amplitude of the stress or strain, as well as the mean stress or strain and the temperature, are kept at a constant level by means of PID control in order to compensate for creep or relaxation effects during the test. In the case of linear-viscoelastic material behaviour and a normal stress state, the temporal changes in stress and deformation in the steady state have the same frequency but different phase angles (Eq. (2) and (3)) (Fig. 4), where δ is the phase angle, which can take values between 0 and π/2.

| (2) |

| (3) |

Eq. (4) applies to the relationship between the stress duration t and frequency f or angular frequency ω:

| (4) |

| Fig. 4: | Schematic structure of the test system and temporal change in stress and strain during DMA using forced vibrations |

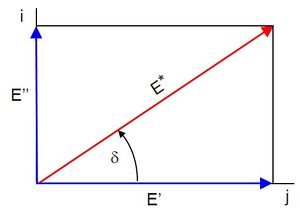

Due to the phase shift δ between stress σ and strain ε, the modulus of elasticity is introduced as a complex parameter E* to describe the stress–strain relationship. The complex modulus can be viewed as a vector in the complex number plane (Fig. 5), whose direction is determined by the phase angle δ and whose magnitude is determined by the ratio of the amplitude values of stress and strain (Eq. 5):

| (5) |

| Fig. 5: | Description of the complex tensile modulus from the DMTA |

Using simple trigonometric relationships, a split into a real part E' (storage module) and the imaginary part E'' (loss module) can be made according to Eqs. (6) and (7), whereby the storage module is of particular interest from an engineering perspective.

| (6) |

| (7) |

The ratio of loss and storage modules results in the loss factor tan δ, which characterises the damping behaviour of the material (Eq. 8).

| (8) |

As a rule, the dynamic modulus of elasticity is slightly higher than the modulus of elasticity from the [Quasi-static Test Methods|quasi-static tests]] due to the oscillating stress. The forced vibration method is limited to frequencies below the resonance frequency of the test specimen. The measurement can be controlled by both strain and stress (see: tensile test control), which allows the complex modulus E* and the complex test specimen compliance C* to be determined.

Due to their wide range of applications (torsion, tension, bending and shear), forced vibration methods now play a dominant role in the dynamic- mechanical analysis of polymer materials.

An approximate determination of the modulus of elasticity is also possible using the torsion vibration test from the shear modulus G if the Poisson's ratio μ is known in the corresponding temperature interval (Eq. 9).

| (9) |

Ultrasound testing

In the high-frequency range, the dynamic modulus of elasticity can also be determined using a dielectric measuring station, or the propagation of sound and ultrasonic waves can be used to determine the characteristic values [9, 10].

Above the resonance frequency, the wavelength λ of the oscillating mechanical stress becomes small in comparison to the test specimen dimensions. This makes it possible to use the characteristics of wave propagation in the material to determine the viscoelastic properties. The measurements are usually carried out using ultrasound (f > 20 kHz) in the pulse-echo ultrasonic technique or ultrasonic transmission technique [1]. The sound velocities c (Eq. 10) and the sound absorption coefficient α (Eq. 11) are determined from the acoustic path length d and the associated pulse transit time t, as well as the amplitudes A1 and A2 at different path lengths d1 and d2.

| (10) |

| (11) |

Using longitudinal waves (cL, αL) and transverse waves (cT, αT), the longitudinal wave modulus L and the shear modulus G can be determined if the density ρ of the material is known. With low attenuation (α λ/2π << 1), Eqs. (12) and (13) apply approximately.

| (12) |

| (13) |

The longitudinal wave and shear modulus can be used to calculate the modulus of elasticity E' (Eq. 14) in accordance with elasticity theory, which depends on the ratio of the propagation velocities of transverse and longitudinal waves.

| (14) |

Ultrasonic measurements are usually performed at frequencies between 100 kHz and 100 MHz. The upper end of the frequency range is determined by the strong increase in damping. Working in this wide frequency range requires the use of different vibration sensors. Relatively large frequency ranges can be recorded after broadband excitation using Fourier or wavelet analysis (see: frequency analysis).

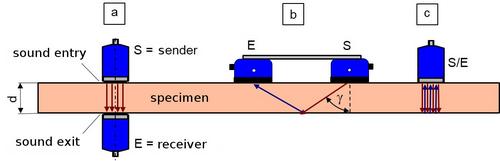

A relatively simple method for determining the modulus of elasticity using ultrasound is to use plate-shaped test specimens of known thickness d and density ρ (Fig. 6).

| Fig. 6: | Schematic representation of the ultrasonic transmission technique with standard sensors (a) and angle beam sensors (b) as well as the pulse-echo technique (c) |

When using standard sensors (Figs. 6a and c), longitudinal waves are used for measurement. It should be noted that with the pulse-echo technique, the transit time of the ultrasound is twice as long as with the transmission method. The transit time Δt can then be measured from the A-scan in direct coupling or immersion bath technique with known thickness and angle of incidence γ according to Eq. (15) (transmission) or (16) (pulse-echo technique) and the longitudinal wave velocity cL can be calculated. The traverse wave velocity cT is determined using angle beam sensors according to Eq. (17).

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

Provided that the Poisson's ratio µ for the test temperature T is known, the modulus of elasticity E can then be calculated using Eq. (18) and the shear modulus G using Eq. (19), bearing in mind that these characteristic values are frequency-dependent.

| (18) |

| (19) |

See also

- Elastic modulus – Examples and material values

- Elastic modulus – Ultrasonic measurement

- Energy elasticity

- Shear modulus

- HOOKE´s law

References

| [1] | Lüpke, T.: Fundamental Principles of Mechanical Behavior. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, pp. 75–77 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-8807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [2] | ISO 527-1 (2019-04): Plastics – Determination of Tensile Properties – Part 1: General Principles |

| [3] | ISO 527-2 (2025-06): Plastics – Determination of Tensile Properties – Part 2: Test Conditions for Moulding and Extrusion Plastics |

| [4] | ISO 178 (2019-08): Plastics – Determination of Flexural Properties |

| [5] | ISO 604 (2002-03): Plastics – Determination of Compressive Properties |

| [6] | Bierögel, C.: Bend Test on Polymers. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S.] (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, pp. 133–143 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |

| [7] | ISO 6721-1 (2019-04): Plastics – Determination of Dynamic Mechanical Properties – Part 1: General Principles |

| [8] | ISO 6721-4 (2019-05): Plastics – Determination of Dynamic Mechanical Properties – Part 4: Tensile Vibration – Non-resonance Method |

| [9] | ISO 6721-8 (2019-04): Plastics – Determination of Dynamic Mechanical Properties – Part 8: Longitudinal and Shear Vibration – Wave-propagation Method |

| [10] | ISO 6721-9 (2019-04): Plastics – Determination Dynamic Mechanical Properties – Part 9: Tensile Vibration – Sonic-pulse Propagation Method |

| [11] | Matthies, K. u. a.: Dickenmessung mit Ultraschall. Deutscher Verlag für Schweisstechnik (DVS), Berlin, 2nd Edition (1998) (ISBN 3-87155-940-7; see AMK-Library under M 44) |