Crack Propagation Energy: Difference between revisions

Oluschinski (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{Language_sel|LANG=ger|ARTIKEL=Rissverzögerungsenergie}} {{PSM_Infobox}} <span style="font-size:1.2em;font-weight:bold;">A-Bild-Technik</span> __FORCETOC__ ==Definition and significance== The modification of plastics with the aim of improving their mechanical properties is achieved technically by using inorganic fillers such as chalk, talc and glass balls or fibres such as short glass fibre..." |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 08:08, 1 December 2025

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

A-Bild-Technik

Definition and significance

The modification of plastics with the aim of improving their mechanical properties is achieved technically by using inorganic fillers such as chalk, talc and glass balls or fibres such as short glass fibres (E-glass) or C-fibres. The structure that forms at the interface between the matrix and the additive is of crucial importance here. To influence these interface properties, coupling agent are often used, which induce physical and/or chemical interactions in the boundary. A sensitive method for detecting changes in the deformation behaviour at the interface is the instrumented Charpy impact test (ICIT), in which so-called crack propagation energies AR appear in the impact load (F)–deflection (f) diagrams.

These crack propagation energies characterise a reduction in the crack propagation speed and are an expression of dominant stable crack growth. This means that it is no longer possible to evaluate toughness using linear-elastic fracture mechanics concepts. This first requires the quantification of the crack propagation energy and subsequently the determination of crack resistance curves (R curves) to describe the qualitatively different material behaviour.

With regard to the use of conventional characteristic values of notch impact toughness to characterise changes in the deformation behaviour in the interface, it becomes clear that possible misinterpretations arise not only from the well-known fact (see: instrumented Charpy impact test) that

- large forces (loads) and small deformations (deflections) may, under certain circumstances, deliver the same notch impact energy as a small force and a large deformation,

but also that

- the determined notch impact energy is composed of completely different energy components that must be assigned to different mechanisms.

Application examples from material development

PA/GF fibre composites – Influence of the a/W ratio

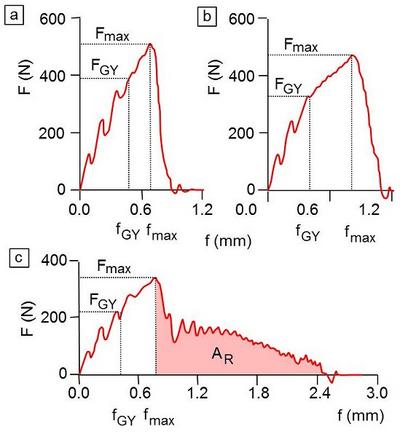

Figure 1 shows the impact load (F)–deflection (f) diagrams for PA/GF fibre composites (see: short-fibre reinforced plastics), whereby the notch depth (a) – specimen width (W) ratio was varied. The relationship between impact load and deflection becomes non-linear as the a/W ratio increases, with the maximum impact load Fmax decreasing and the deflections fmax and fGY increasing.

| Fig. 1: | Impact load (F)–deflection (f) behaviour in ICIT with crack propagation energy in PA-glass fibre composites for a/W ratios: (a) 0.2, (b) 0.3 and (c) 0.45 |

Parts a to c of Figure 1 clearly show that crack propagation energy is a sensitive variable for evaluating deformation behaviour, but is unsuitable as an evaluation parameter because it is not a material parameter due to its geometry dependence (a/W ratio) (see: geometry criterion) and can therefore be used for quality control but not as a target variable in material development.

PE chalk composites – Influence of a coupling agent

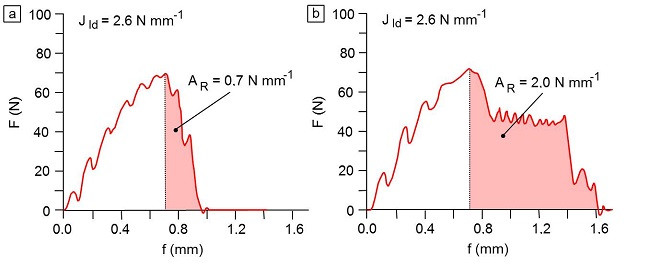

Figure 2 shows the impact load (F)–deflection (f) diagrams recorded using the instrumented Charpy impact test for a PE-HD chalk composite and a PE-chalk composite modified with stearic acid with the same filler volume fraction (φv = 0.15) (see also: particle-filled plastics).

The use of surface-modified additives (coupling agents) changes the requirements for evaluation concepts used to describe toughness behaviour (see: levels of knowledge in fracture mechanics), as there is no longer any dominant unstable crack propagation in the material, which is documented in the F-f diagram by the lack of a pronounced load drop after Fmax and the formation of AR.

| Fig. 2: | Impact load (F)–deflection (f) behaviour in ICIT with crack propagation energy in PE/chalk composites: (a) low coupling agent content and (b) optimal PE/chalk composite |

The J-integral values were determined using the estimation method developed by SUMPTER and TURNER. Figure 2 shows that, with the same crack toughness values as resistance to unstable crack propagation, JId of 2.6 Nmm-1 can result in very large differences in crack propagation energy. Knowledge of the crack propagation energy is of exceptional practical importance, as this energy component clearly represents a toughness reserve.

PP-GF composites – Influence of fibre modification

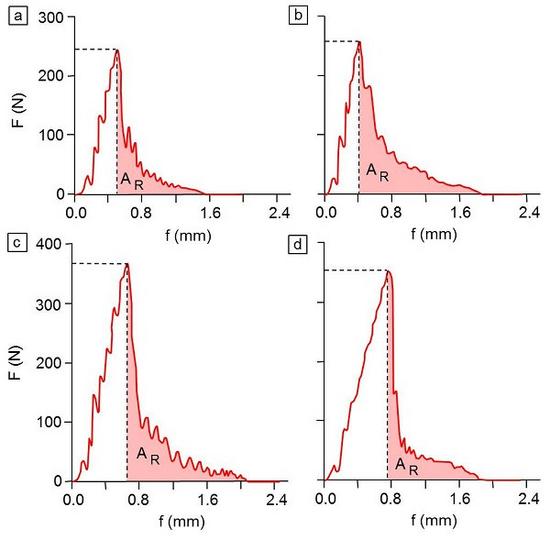

Figure 3 shows the influence of fibre modification with a coupling agent (HV) on the toughness behaviour of GF-reinforced polypropylene. The fibre content of the PP-GF composite was φv = 0.13 and the coupling agents used were 0.2 %, 0.5 % and 1 % HV.

| Fig. 3: | Impact load (F)–deflection (f) diagrams for PP-GF composites with (a) 0 %, (b) 0.2 %, (c) 0.5 % and (d) 1 % HV coupling agent |

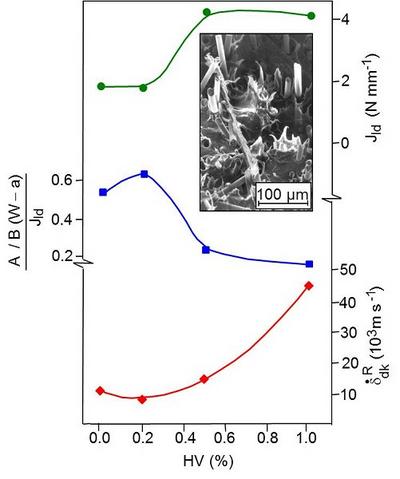

After reaching Fmax, the F-f diagrams show non-negligible crack propagation energies. Up to a coupling agent content of 0.5 %, there is an increase in the maximum impact load, the maximum deflection increases with increasing HV and the crack propagation energy components reach a maximum at 0.2 % coupling agent. At a bonding agent content of HV > 0.2 %, a significant decrease in specific crack propagation energy is observed with a simultaneous increase in crack opening displacement velocity (see: levels of knowledge in fracture mechanics) (Fig. 4).

| Fig. 4: | Relationship between J values, specific normalised crack propagation energy, crack opening displacement velocity and coupling agent content |

However, the J-integral values only show a significant increase in toughness at 0.5 % HV.

Due to the different conclusions that can be drawn from observing the material behaviour before reaching Fmax on the one hand and after reaching Fmax on the other, a fracture mechanical evaluation using the conventional methods described is no longer possible, and it is necessary to switch to determining characteristic values at stable crack growth in order to quantify the energy dissipative processes using fracture mechanical material parameters (see: fracture mechanics).

The recording of the crack resistance (R) curves required for this is explained under crack resistance curve – experimental methods.

Microfractographic investigations of the PP-GF composites have shown that the increase in energy dissipation is associated with fibre pull-out and severe fibrillation of the matrix with the formation of pointed structures (see: ramps, clods and steps) (Fig. 4) (see: fracture model of fibre-reinforced plastics and fibre–matrix adhesion).

See also

- ICIT – Types of impact load–deflection diagrams

- Instrumented Charpy impact test

- Short-fibre reinforced plastics

- ICIT – Experimental conditions

- Polymer blend

References

- Grellmann, W., Seidler, S.: J-integral Analysis of Fibre-reinforced Injection Moulded Thermoplastics. J. of Polymer Engineering 11 (1992) 71–101, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/POLYENG.1992.11.1-2.71

- Seidler, S., Grellmann, W.: Zähigkeit von teilchengefüllten und kurzfaserverstärkten Polymerwerkstoffen. VDI-Fortschr.-Ber., VDI-Reihe 18 Nr. 92, VDI Düsseldorf (1991) (ISBN 3-18-149218-3; see AMK-Library under A 14)

- Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22)