Materials Science

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Materials science (Author: Prof. Dr. H.-J. Radusch)

Materials science as a scientific discipline

Material & Werkstoff

The targeted use of materials such as wood and bone, stone, glass/ceramics and metals as well as polymer materials, composite materials and material composites has been taking place for thousands of years. Materials have characterised entire epochs in the development of mankind, so it is no coincidence that the terms Stone Age, Bronze Age or Iron Age were chosen.

The term “ Werkstoff” (“material”) only emerged in the 19th century and is sometimes used synonymously with the term “material”. According to [1], materials are work equipment of a purely material nature, which are further processed in production processes as work objects and are incorporated into the respective end products. As a rule, these are solids. The quality and properties of the end products or semi-finished products are decisively influenced by the choice of more or less suitable materials.

Czichos [2] provides the following definition: "Werkstoffe (Materials) in the narrower sense are materials in a solid aggregate state from which components and structures can be manufactured. Such materials possess the special property of formative ‘plasticity’ in a broad sense. Only through this can components actually take on a shape developed in the design process later in production. The quality and properties of the finished products are decisively influenced by the choice of suitable materials and manufacturing processes (primary moulding, forming, heat treatment, etc.). Materials testing is used to characterise and ensure quality. Specialist areas that deal with the research and development of materials are materials technology, materials science and materials engineering."

Schmitt-Thomas [3] formulates that the ability to provide suitable materials with the help of available resources is a prerequisite for transferring scientific knowledge into an applicable, useful and civilisationally implementable technology. The extraction and mastery of the material, in the sense of the ability to control its properties and optimally adapt it to the stresses, thus becomes the key that, under the responsibility of the engineer, makes it possible to translate scientific knowledge into quality of life [3].

The Springer-Gabler Wirtschaftslexikon [4] defines the term “Werkstoff” as: "Material, summarising term for those raw materials, auxiliary and operating materials, semi-finished and finished products that are intended to be used as starting and basic materials in the products of a company. Materials are among the elementary production factors. They become part of new products after their form or substance has been changed in the company or through their incorporation into other finished products."

Currently, materials are generally divided into metals (e.g. iron, aluminium), non-metals (e.g. graphite), organic materials (e.g. wood, polymer materials), inorganic non-metallic materials (e.g. ceramics, glass) and semiconductor materials (e.g. silicon).

Schatt [5] has used the term ‘construction material’ since the 5th edition of the reference book ‘Werkstoffe des Maschinen-, Anlagen- und Apparatebaues’ (Materials used in mechanical, plant and apparatus engineering), published in 1975. The classification of materials is based on the requirements in various technical areas of application, such as materials for tools, low temperatures, high temperatures, corrosive stress, wear, connections, etc. The term ‘construction material’ is used for this purpose. In English, the term ‘construction material’ or ‘engineering material’ is used for this.

Wikipedia [6] provides the following definition of the term material: "A material is a substance or a mixture of substances that forms an object. Materials can be pure or impure, animate or inanimate matter. Materials can be classified on the basis of their physical and chemical properties or their geological origin or biological function. Materials science deals with materials, their properties and their applications."

In contrast to the term material, the term Werkstoff implies a purpose for which a component or construction is to be manufactured. The distinction between the terms Werkstoff and material in German-speaking countries is not made in English. The term material is generally used here.

From materials technology to materials science

In the middle of the 19th century, systematic but still strongly empirical research into the properties of steel, iron or light metals such as aluminium and ceramic materials began, from which the field of materials technology developed. The term ‘Werkstoffkunde (materials technology)’ was used, whereby the word ‘-kunde’ was intended to express the fact that it encompassed all empirically recorded facts about materials – initially mainly metallic materials [7]. At the same time, ‘-kunde’ was also the usual German term for other fields of knowledge that dealt with the study of the same. In English-speaking countries, the term “materials science” was immediately coined and used for “Werkstoffkunde (materials technology)” [8, 9]. It was mainly metallurgy from which materials technology emerged as a scientific discipline [10].

At the beginning of the 20th century, a more differentiated view of materials developed as industrialisation progressed. In addition to conventional metals, non-metallic-organic and non-metallic-inorganic materials gained increasing economic importance, which resulted in the need to teach new subjects relating to all material groups in vocational training and at colleges and universities.

The historical increase in knowledge was the starting point for the textbook ‘Einführung in die Werkstoffwissenschaft (Introduction to Materials Science)’ [11], first published in 1972 by Prof. Dr Werner Schatt, Dreden, which is based on a uniform and at the same time ordering approach to the structure, the type of arrangement and the degree of order of the building blocks and places structure–property relationships at the centre of the descriptions. Materials science deals with the atomic structure, the resulting microscopic structure, the resulting macroscopic properties and in particular with the targeted improvement of the application possibilities of all material groups [11] from a generalised methodological point of view.

With the diversity of materials and the deepening knowledge, it subsequently became common in German-speaking countries to use the terms ‘materials science’ and ‘materials engineering’ in research, education and practice. Currently, the term ‘Materialwissenschaft’ or ‘Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik’ seems to be established in German-speaking countries to characterise the field of materials science, which also corresponds to the English-language term ‘materials science’ or ‘materials science and technology’ [12].

While materials science or materials science focuses on the structural aspects of all material groups, materials engineering focuses more on the manufacturing and processing methods of materials, the determination of their physical and mechanical properties and the structure–property relationships, taking into account the influence of processing conditions and application behaviour. In general, however, the subjects of teaching and research are intertwined.

Schatt and Worch [13] pointed out that the uniform approach to all materials means that there can only be one ‘Werkstoffwissenschaft’. To speak in the plural would be to hinder the epistemological development of the scientific discipline in its unity. Regardless of this, there are also counterexamples where the plural has been used in institutions, in textbook titles [14] and in current degree programme titles [15, 16]. Currently, a broader variation of terms is used to describe this field of science in order to express specifics or specialisations. In Germany, Austria and Switzerland, for example, the following terms are used to describe degree programmes

- Werkstoffwissenschaft

- Werkstoffwissenschaften

- Materialwissenschaft

- Materialwissenschaften

- Werkstofftechnik

- Werkstoff- und Materialwissenschaften

- Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik

- Advanced Materials Science and Engineering (En)

- Materials Engineering (International Profile)

The degree programme title ‘Werkstoffwissenschaft’ in the singular is now only used by the TU Dresden, TU Ilmenau and the University of Jena.

The TU Berlin has renamed the previous degree programme ‘Werkstoffwissenschaft’ to ‘Materials Science and Engineering’ [17].

Irrespective of the different names, materials science has now firmly established itself as an independent scientific discipline in the basic technical disciplines, e.g. in mechanical engineering or process engineering, by integrating empirically gathered factual knowledge with theoretical laws. This has led to insights that have opened up new fields of application for the special properties of materials, e.g. in medicine and medical technology, aerospace, microelectronics and computer technology or in competitive sports.

The interdisciplinary character of materials science

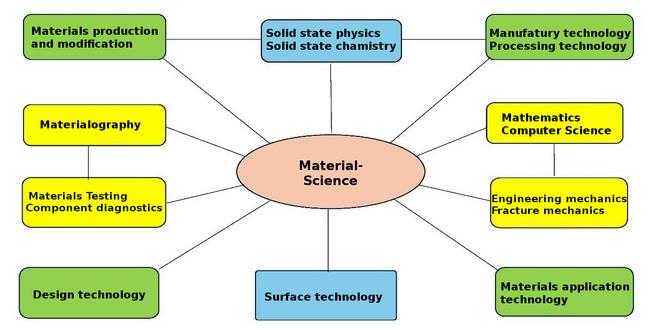

Materials science has a pronounced interdisciplinary character (see figure), which on the one hand leads to a concise further development of this field of science and on the other hand to a great diversity in the field of materials science.

| Fig.: | The interdisciplinary character of materials science |

The picture also shows the particular specificity of materials science, which on the one hand represents the link between materials production and modification and manufacturing and processing technology and on the other hand between design theory and materials application technology. This results in a multitude of dialectical interactions between the individual specialist areas. For example, the practical utilisation of findings from materialography (metallography, plastography, ceramography) and materials testing/fracture mechanics has only become possible through the further development and application of new materials. Corresponding to materials science, design engineering, materials processing and materials application technology have become firmly established, which is also reflected in the curricula of materials science degree programmes. The subject of application technology is designing with materials that may have been modified to meet application-specific requirements, whereby the designer's task is to realise the dimensioning and design of moulded parts, which today is carried out with the aid of computer-aided CAD/CAM processes such as ANSYS or CREO (formerly pro/ENGINEER), using reliable material data based on materials science.

Within materials science and materials engineering, materials testing and technical fracture mechanics have established themselves as separate fields of knowledge. The disciplines of quality assurance and quality management, which are integrated into the study programmes, are also becoming increasingly important, with quality management being understood as the entirety of quality-related activities. An essential component is quality testing, which itself can take many different forms. An important but technically difficult step to realise is the online integration of materials testing procedures into the respective production process to optimally ensure the quality requirements of the product and the process design. Material diagnostics/damage analysis involves the interaction of methods for analysing the material composition (material analysis), the structural composition, the mechanical, thermal, electrical and optical properties and the reaction with the environment. Particular progress in terms of gaining knowledge is being made in the further development of hybrid methods of materials diagnostics [18–21], which is understood to mean the in-situ coupling of mechanical and fracture mechanics experiments with the increasingly important non-destructive testing methods, such as acoustic emission analysis , thermography or laser extensometry. The aim is always to increase the informative value of classic testing methods and to derive possibilities for quantifying damage states or limit values (see also damage analysis) [18]. The fields of metrology and automation technology are also an important part of engineering training, the further development of which has led to new requirements for materials testing in quality, safety and environmental management.

Solving environmental and climate policy problems in the production, processing and application of all material groups will require even greater interdisciplinary co-operation in the future. Polymer materials should be given particular attention in this context. When polymer materials are used, their properties must be tailored more specifically to the application in order to ensure a long product life and high recyclability. This requires solutions based on materials science, which can only be achieved through interdisciplinary co-operation.

Modern methods of structural analysis, which form an important basis for material development, are of great importance here. Today, methods such as X-ray methods, CT-supported methods, spectroscopic methods, calorimetric methods, electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy methods as well as combined methods are available that guarantee a complete explanation of the structural hierarchy.

For the important field of mechanical property characterisation, this requires the use of modern methods of material diagnostics [18, 19] and micro- or nanomechanics [22, 23].

Characteristic features of materials science

Materials science is characterised by its affiliation to the engineering sciences, the application of a uniform approach to the various groups of materials and its strong interdisciplinary nature.

In order to establish structure–property relationships and explain the interrelationships, findings from other scientific and technical disciplines – as already explained in the examples of solid state physics and solid state chemistry or production and application technology – must be incorporated.

The study of materials science is characterised by a strong practical orientation, numerous laboratory practicals, project work and Bachelor's and Master's degrees that are generally geared towards practice [24].

Material economic aspects play a central, constantly growing role in the use of materials. The material intensity, which sets the material costs in relation to the production volume, is considered as an evaluation parameter here. This parameter can be decisively influenced by a number of measures, such as substitution of a material, reduction of the quantity used, better utilisation of the properties, longer service life, use of rework-free manufacturing processes, application of lightweight construction principles, closed material cycles, etc.

The complexity of the technical applications of materials and their influence on the development of many branches of industry characterise the urgent need for the interdisciplinary nature of materials science.

The increasing interdisciplinary orientation of materials science is expressed, for example, in areas and applications such as the automotive industry, aerospace, sensor technology, robot drives and micromanipulators or biomedical applications. The development of shape memory materials is a striking example of this [25, 26].

The further development and intensification of the interdisciplinary nature of materials science can also be seen in the new courses on offer. For example, since the 2024/25 academic year, the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg has been offering a new interdisciplinary bachelor's degree programme in AI materials technology, in which materials science and materials engineering, natural sciences and computer science are combined in an innovative way, taking special account of the possibilities offered by artificial intelligence [27].

The history of materials technology/materials science university education in Merseburg/Halle

The beginnings of materials technology training at the former “Carl Schorlemmer” Technical University of Chemistry in Merseburg date back to 1959 and were strongly modelled on the training offered at the Technical University of Dresden and the Freiberg Mining Academy (Bergakademie Freiberg) [28]. Materials science training at the TH Merseburg initially took the form of a specialisation in materials technology (Werkstoffkunde) within the subject area of process engineering. In line with the current state of science, the subject of materials technology was almost exclusively concerned with metals and metal alloys, while inorganic non-metallic and polymer materials were only briefly dealt with, as they were of little industrial importance as construction materials at the time. With the first theses of the diploma students, the thematic focus changed and technological aspects of polymer materials were increasingly dealt with. This trend intensified at the end of the 1960s, as the production and variety of polymer materials had increased considerably in the meantime.

In the mid-1970s, a separate degree programme in materials engineering was developed in cooperation with the GDR universities, which offered good conditions for the training of materials engineers [29]. The specific feature of materials engineering in Merseburg was its specialisation in the materials group of polymers. In 1973, the specialisation was called ‘Materials Application’ (polymer materials). This was later specified as ‘Materials Engineering (Polymer Materials Engineering)’. This stage of development was characterised by intensive cooperation between engineers and scientists.

In 1976, the formation of a Materials Engineering section at the TH Merseburg recognised the growing importance of materials science for scientific and technological progress. The rapidly growing knowledge of material structure, the increasingly efficient methods and equipment and the more complex approaches led to the terms materials engineering and materials science increasingly replacing the term materials technology.

After the political change in East Germany and reunification in 1990, some serious changes occurred in both teaching and research. The Department of Materials and Processing Technology, which had existed until reunification, was reorganised into a Department of Materials Science with an Institute of Materials Science and an Institute of Materials Technology [29].

After the dissolution of the Leuna-Merseburg Technical University (THLM) in 1993, teaching and research in the field of materials science was continued at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg on the recommendation of the Science Council (Wissenschaftsrat). At this time, student education was based on a 10-semester degree programme in ‘Werkstoffwissenschaft (Materials Science)’ with a focus on materials engineering and plastics technology.

In addition, a postgraduate course in ‘Materials Science’ was established in 1997, specialising in plastics technology and surface technology, which was aimed in particular at graduates of universities of applied sciences for the purpose of obtaining a university degree in the field of materials science.

In 1999, a modular study concept was introduced and the ‘Werkstoffwissenschaft’ degree programme was extensively revised. The previous division into basic and advanced study programmes was replaced by the definition of modules. The programme was streamlined and the standard period of study shortened to 10 semesters. Structured in this way, the Werkstoffwissenschaft (Materials Science) degree programme had three specialisations in the fields of materials technology, plastics technology and biomedical materials by the 2003 enrolment year [30].

In connection with the establishment of an innovation college funded by the DFG between 1994 and 2000 on the subject of ‘Heterogeneous Polymer Materials’, an English-language Master's degree programme in ‘Applied Polymer Science’ (from 2009 ‘Polymer Materials Science’) was established in 2001.

Despite the positive development of engineering education in Merseburg/Halle, complex structural changes in society and the economy led to the termination of engineering education at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg in 2006 [31]. The Faculty of Engineering was transferred to a temporary Centre for Engineering Sciences, which was finally closed in 2016 following a decision by the state government of Saxony-Anhalt [32].

The English-language Master's degree programme in Polymer Materials Science, formerly established at the Faculty of Engineering, was transferred to the Faculty of Natural Sciences II at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg and continued. The Polymer Materials Science degree programme is today an interdisciplinary Master's degree programme run in cooperation between Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg and Merseburg University of Applied Sciences. This Master's programme provides a versatile education in one of the key industrial growth sectors. The research-oriented programme offers specialisations in the fields of polymer synthesis, polymer physics and polymer technology.

See also

- Material science & plastics

- Material & Werkstoff

- Micromechanics & Nanomechanics

- Materials testing

- Polymer testing

- Polymer diagnostic

References

| [1] | https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portal:Werkstoffe |

| [2] | Czichos, H., Hennecke, M. (Hrsg.): HÜTTE – Das Ingenieurwissen, 33., aktualisierte Auflage, Springer Berlin Heidelberg (2008); ISBN 978-3-540-71851-2 bzw. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Werkstoff |

| [3] | Schmitt-Thomas, K. G.: Werkstoff in Geschichte und technischer Entwicklung. In: Metallkunde für das Maschinenwesen. Springer Berlin Heidelberg (1990); https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-93451-3_2 |

| [4] | https://wirtschaftslexikon.gabler.de/definition/werkstoffe-49420 |

| [5] | Schatt, W., Simmchen, E., Zouhar,G. (Hrsg.): Konstruktionswerkstoffe des Maschinen- und Anlagenbaues. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie Stuttgart (1998); ISBN 3-342-00677-3; see AMK-Library under L 4 |

| [6] | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Material |

| [7] | Eisenkolb, F.: Einführung in die Werkstoffkunde. Verlag Technik Berlin (1958); see AMK-Library under L 24 |

| [8] | Hummel, R. E.: Understanding Materials Science History, Properties, Applications (2nd Ed.). New York, NY, Springer New York, (2005). LLC; ISBN 978-0-387-26691-6 |

| [9] | Timeline of materials technology; In: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_materials_science |

| [10] | Cahn, R. W.: Metallurgy, the Father of Materials Science. Tsingiiua Science and Technology, Volume 7, Number 1 (2002); ISSN 1007-0214 01/21 pp. 1 – 5 |

| [11] | Schatt, W. (Hrsg.): Einführung in die Werkstoffwissenschaft. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie (1972); see AMK-Library under L 3-1 |

| [12] | https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Materialwissenschaft_und_Werkstofftechnik#Begriffsdefinition |

| [13] | Schatt, W., Worch, H. (Hrsg.): Werkstoffwissenschaft. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie Stuttgart (1996); see AMK-Library under L 3-2 |

| [14] | Ilscher, B.: Werkstoffwissenschaften. Eigenschaften, Vorgänge, Technologien. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York (1987); see AMK-Library under L 83 |

| [15] | https://www.hochschulkompass.de/ingenieurwissenschaften/werkstoff-und-materialwissenschaften.html |

| [16] | StudiScan: Deutschland / Österreich /Schweiz; https://www.studieren-studium.com/master/materialwissenschaften-und-werkstofftechnik |

| [17] | https://www.tu.berlin/studieren/studienangebot/gesamtes-studienangebot/studiengang/materialwissenschaft-und-werkstofftechnik-b-sc |

| [18] | Biermann, H., Krüger, L.: Moderne Methoden der Werkstoffprüfung. Wiley-VCH Verlag (2015); ISBN 978-3-527-33413-1; see AMK-Library under M 35 |

| [19] | Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Hrsg.): Kunststoffprüfung. Carl Hanser Verlag, München (2025); ISBN 978-3-446-44718-9; e-book ISBN 978-3-446-48105-3; see AMK-Library under A 23 |

| [20] | Blumenauer, H.: Werkstoffprüfung. Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie. Leipzig (1975,1978); Stuttgart (1994); ISBN 978-3-342-00547-6; see AMK-Library under M 1 to M 3 |

| [21] | Grellmann, W.: Neue Entwicklungen in der Werkstoffprüfung – Herausforderungen an die Kennwertermittlung. Deutscher Verband für Materialforschung und -prüfung, Berlin (2011); ISBN 978-3-9814516-1-0; ISSN 1861–8154; see AMK-Library under A 13 |

| [22] | Michler, G. H.: Mechanik–Mikromechanik–Nanomechanik. Vom Eigenschaftsverstehen zur Eigenschaftsverbesserung. SpringerSpektrum (2024); ISBN 978-3-662-66965-5; e-book: ISBN 978-3-66966-2; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-66966-2; see AMK-Library under F 34 |

| [23] | Michler, G. H.: Kompakte Einführung in die Elektronenmikroskopie. Techniken, Stand, Anwendungen, Perspektiven. SpringerSpektrum Wiesbaden (2019), ISBN 978-3-658-26687-5; e-book: ISBN 978-3-658-26688-2; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-26688-2; see AMK-Library under F 21 |

| [24] | Altenbach, H., Bachmann, T., Orzschig, W.: Neue Aspekte der werkstoffwissenschaftlichen Lehre. In: Leps, G., Kausche, H.: 40 Jahre Werkstofftechnik Merseburg. Selbstverlag (1990) pp. 45–52; ISBN 3-86010-578-7; see AMK-Library under L 89 |

| [25] | Lendlein, A., Langer, R.: Biodegradable, elastic shape-memory polymers for potential biomedical applications. Science 296 (2002) 1673-1676 |

| [26] | Radusch, H.-J., Kolesov, I., Gohs, U., Heinrich, G.: Multiple shape-memory behavior of polyethylene/polycyclooctene blends cross-linked by electron irradiation. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 297 (2012) 1225–1234; https://doi.org/10.1002/mame.201200204 |

| [27] | https://www.mat.studium.fau.de/studiengaenge/neu-ki-materialtechnologie/ |

| [28] | Pfefferkorn, W.: 40 Jahre Werkstofftechnik in Merseburg. In: Leps, G., Kausche, H.: 40 Jahre Werkstofftechnik Merseburg. Selbstverlag (1990) pp. 19–33; ISBN 3-86010-578-7; see AMK-Library unter L 89 |

| [29] | Radusch, H.-J., Werkstoffwissenschaft, in: 50 Jahre Hochschule in Merseburg, Merseburger Beiträge zur Geschichte der chemischen Industrie Mitteldeutschlands, 9 (2004)1, pp. 119–128, SCI Merseburg 2004 |

| [30] | Studienordnung für den Studiengang Werkstoffwissenschaft am Fachbereich Ingenieurwissenschaften an der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle–Wittenberg vom 31.03.2003, Amtsblatt der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 13. Jahrgang, Nr. 8 vom 16. Dezember 2003, p. 30 |

| [31] | https://www.iw.uni-halle.de/status/ |

| [32] | https://dubisthalle.de/uni-halle-schafft-ingenieurwissenschaften-endgueltig-ab |