Adhesive Joints – Determination of Characteristic Values: Difference between revisions

Oluschinski (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{Language_sel|LANG=ger|ARTIKEL=Klebverbindungen – Kennwertermittlung}} {{PSM_Infobox}} <span style="font-size:1.2em;font-weight:bold;">Adhesive joints ‒ Determination of characteristic values (Author: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Stephan Marzi)</span> __FORCETOC__ ==Determination of fracture mechanics values on DCB-specimens for adhesive joints== As shown in '''Figure 1''', the DCB-specimen is preferably used to determine the (critical) Energy Release Rate|e..." |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 13:06, 28 November 2025

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Adhesive joints ‒ Determination of characteristic values (Author: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Stephan Marzi)

Determination of fracture mechanics values on DCB-specimens for adhesive joints

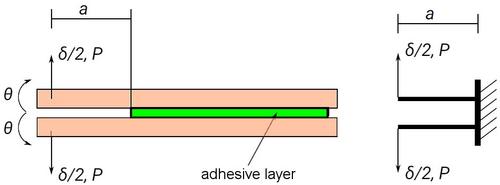

As shown in Figure 1, the DCB-specimen is preferably used to determine the (critical) energy release rate GIc in Mode I. However, there is also work in which DCB-specimens are used in Mode III [1] or in Mixed-Mode I+III [2, 3].

The DCB-specimen consists of two beam-shaped joining parts (or substrates), which are only allowed to deform linearly and elastically during the test and are joined with the adhesive to be tested. In contrast to the evaluation methods mentioned above, which are based on singular stress fields at the crack tip and the associated concept of stress intensity factors, methods based on beam theory are usually used in the case of adhesive joints. Further details are regulated in ISO 25217 [4].

| Fig. 1: | Sketch and nomenclature of a DCB test on adhesive joints (left) and replacement model (right) |

The beam theory methods are based on the IRWIN-KIES equation,

| (1) |

with the specimen compliance C = δ/P and the current crack length a, and are thus based on the linear-elastic BERNOULLIAN beam theory. In particular, the IRWIN-KIES equation also implies that

- the force–displacement (P‒δ) curve is linear and runs through the origin in the case of unloading,

- the adhesive behaves infinitely stiff and ideally brittle,

- the crack length a is large enough (a/h > 10) to be able to use the substitute model of two cantilever beams of length a, and

- the two cantilever beams can be regarded as firmly clamped at the current crack position.

Simple Beam Theory (SBT)

Simple Beam Theory (SBT) assumes that the above conditions are all fulfilled. In this case, the IRWIN-KIES equation is reduced to

| (2) |

Here, B, h and ES are the width, height and modulus of elasticity of a joining part. In reality, adhesives are significantly softer and more flexible than the substrates and therefore cannot be considered infinitely stiff. Consequently, there is usually no fixed restraint at the position of the crack tip and Eq. (2) underestimates the energy release rate.

Corrected Beam Theory (CBT)

To determine correct energy release rates, ISO 25217 [4] recommends the use of a modified form of Eq. (2), in which the crack length a is corrected by a restraint correction length Δ,

| , | (3) |

in order to take account of the compliance of the restraint in the equivalent model. The correction length ∆ can be determined experimentally via a compliance calibration and follows directly from a linear regression between C1/3 and a, as Fig. 2 (left) illustrates.

| Fig. 2: | Compliance calibration: CBT (left) and ECM (right) |

Experimental Compliance Method (ECM)

As an alternative to the corrected beam theory (CBT), the experimental compliance method (ECM) can also be used, which was proposed by Berry [5] in 1963 and is also known as BERRY's method. While the CBT calibrates the beam model by adjusting the cantilever length and thus remains physically descriptive, the ECM is based on a calibration of the order n, with which the compliance C depends on the crack length a, C ∞ an. The IRWIN-KIES equation then takes the form on

| (4) |

The exponent n can be determined in a similar way to the correction length Δ (CBT) via a compliance calibration and results from the slope of a linear regression between log (a) and log (C), as illustrated in Fig. 2 (right).

Evaluation via rotation measurement (J-integral)

The evaluation of the energy release rate GIc on the basis of equations (2), (3) and (4) requires a determination of the current crack length in the experiment. This usually requires increased effort in the measurement setup and is often subject to subjective evaluations and inaccuracies (e.g. in the visual analysis of image recordings). If the rotation Θ = 3δ/4a of the load application point is selected as the degree of deformation of the test specimen, then the IRWIN-KIES equation is simplified to

| (5) |

and only depends on the load P and the rotation Θ of the load application points. Although this procedure requires additional sensors to measure the rotation, compliance calibration is no longer necessary and the energy release rate can be calculated directly from the measured variables P and Θ. The energy release rate, if calculated according to Eq. (5), is usually referred to as JIc , as Eq. (5) can also be found in an alternative way and then corresponds to the J-integral according to Rice [6].

Since this evaluation method does not require knowledge of the crack position and the bending stiffness, (GIc) can also be used as a controlled variable, provided that the controller of the testing machine technically permits this [7]. If no rotation measurement is possible, such a control can be achieved by using the equation

| , | (6) |

however, the bending stiffness EI must then be known from analytical estimates or calibration tests.

See also

References

| [1] | Loh, L., Marzi, S.: An out-of-plane loaded double cantilever beam (ODCB) test to measure the critical energy release rate in mode III of adhesive joints. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 83 (2018) 24–30, special issue on joint design, DOI: 10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2018.02.021 |

| [2] | Loh, L., Marzi, S.: Mixed-mode I+III tests on hyperelastic adhesive joints at prescribed mode-mixity. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 85 (2018) 113–122, DOI: 10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2018.05.024 |

| [3] | Loh, L., Marzi, S.: A mixed-mode controlled DCB test on adhesive joints loaded in a combination of modes I and III. Procedia Structural Integrity 13 (2018) 1318–1323, ECF22 ‒ Loading and Environmental effects on Structural Integrity, DOI: 10.1016/j.prostr.2018.12.277 |

| [4] | ISO 25217 (2009-5): Adhesives – Determination of the Mode I Adhesive Fracture Energy of Structural Adhesive Joints using Double Cantilever Beam and Tapered Double Cantilever Beam Specimens |

| [5] | Berry, J. P.: Determination of fracture surface energies by the cleavage technique. Journal of Applied Physics 34 (1963) 1, 62–68, DOI: 10.1063/1.1729091 |

| [6] | Rice, J. R.: A path independent integral and the approximate analysis of strain concentration by notches and cracks. Journal of Applied Mechanics 35 (1968) 2, 379–386, DOI: 10.1115/1.3601206 |

| [7] | Schrader, P., Schmandt, C., Marzi, S.: Mode I creep fracture of rubber-like adhesive joints at constant crack driving force. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 113 (2022) 103079, DOI: 10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2021.103079 |