Absorption Sound Waves: Difference between revisions

Oluschinski (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{Language_sel|LANG=ger|ARTIKEL=Absorption Schallwellen}} {{PSM_Infobox}} <span style="font-size:1.2em;font-weight:bold;">Absorption sound waves</span> __FORCETOC__ ==Physical fundamentals== When a sound wave hits an external or internal interface (see also: phase boundary surface), it will partially penetrate this material (transmission sound waves), but will also be partially reflected b..." |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 13:02, 28 November 2025

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Absorption sound waves

Physical fundamentals

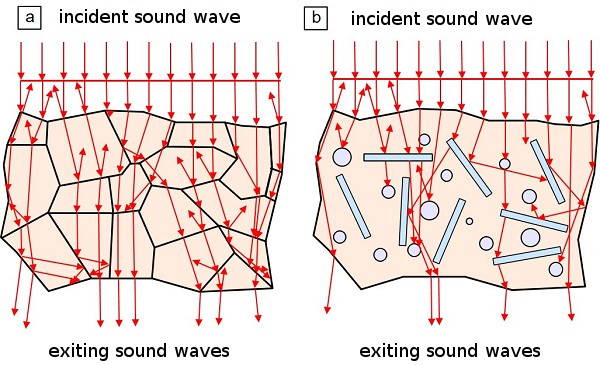

When a sound wave hits an external or internal interface (see also: phase boundary surface), it will partially penetrate this material (transmission sound waves), but will also be partially reflected back at the surface or interface (see also: ultrasonic waves reflection). In the material behind the interface, the wave is subject to material-specific absorption or dissipation, whereby the intensity I0 of the incident wave is reduced. At the same time, especially in polycrystalline materials (grain boundaries in metals) and in heterogeneously structured composite plastics (particles and fibres in fibre-reinforced plastics (FRP)), the ultrasonic wave is scattered (Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1: | Scattering at internal interfaces a) in polycrystalline metals and b) in filled and reinforced plastics with perpendicular sound incidence |

This effect becomes clear when comparing sound attenuation, i.e. the decrease in sound pressure due to the geometric divergence of the sound wave, with the actual reduction in sound pressure [1–5]. Absorption refers to the partial conversion of sound energy into thermal energy, whereby the structure is excited to vibrate. Strictly speaking, the dissipation of sound energy refers not only to its conversion into thermal energy, but also into other forms of energy, making absorption a special case of dissipation. This thermal effect can be utilised in a non-destructive manner (see also: non-destructive polymer testing) by exciting internal defects, such as cracks or delaminations, using ultrasound and recording the thermal emission, e.g. by means of video thermography (ultrasonic lock-in thermography). In the case of scattering, the ratio of the size of the inhomogeneity (grain size, particles or fibres) to the incident wavelength λ has a decisive influence on the extent and type of scattering, which is why this influencing factor also depends on the frequency of the ultrasound [5]. In contrast to scattering, sound absorption also depends on the type of wave and the frequency, with absorption increasing proportionally with the ultrasonic frequency.

Sound absorption coefficient α

In isotropic materials without internal heterogeneities, only absorption occurs, but no scattering (see: ultrasonic waves reflection and refraction sound waves) [4]. In ultrasonic testing technology, scattering and absorption, generally referred to as sound attenuation, cause a reduction in the registered sound waves in the transmission or pulse-echo method. The parameters absorption coefficient and absorption degree are used for the quantitative representation of sound absorption, whereby the sum of the transmitted and dissipated portions is referred to as absorbed sound energy (sound absorption). The absorption coefficient α or linear attenuation coefficient μ (also known as the damping constant) describes the reduction in intensity I0 of a plane ultrasonic wave in a medium, whereby geometric losses due to divergence are not taken into account here. This value is therefore a material-specific constant for sound attenuation.

The frequency-dependent sound absorption coefficient α is a measure of the intensity of sound I0 lost in a medium due to sound transmission τ and sound dissipation δ (Eq. 1), which thus describes the absorption capacity of a material.

| α = τ + δ | (1) |

An absorption degree α of α = 0 means that no absorption takes place and all incident sound is reflected. Conversely, α = 1 means that the incident sound is completely absorbed, and no reflection takes place.

Example of sound absorption in plastics

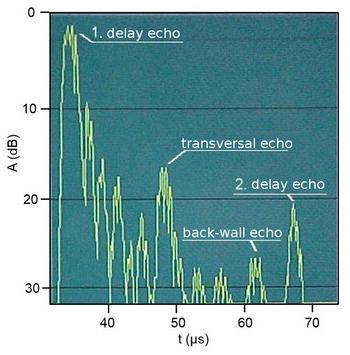

The practical effects of absorption losses in ultrasound testing can be illustrated by comparing metallic materials with plastics. Since even unfilled plastics exhibit significantly higher sound attenuation due to absorption, the penetration depth of these materials is lower, especially at higher test frequencies (Fig. 2).

| Fig. 2: | Influence of the lead-in distance on the signal response (A-scan) for an UP resin DERAKANE 411 with whirling fibre (WF) at a thickness d = 34.4 mm |

When reinforced plastics or particle-filled plastics are tested with ultrasound, strong scattering also occurs at internal heterogeneities such as fibres, mats or particles. The energy losses cause a significant reduction in the penetration capability of the ultrasound. The conventional A-scan is therefore overlaid by many scattering and reflection signals (gras), which often makes reliable detection of the back wall echo impossible [4, 6].

See alao

- Transmission sound waves

- Phase boundary surface

- Ultrasonic wave reflection

- Ultrasonic weld inspection

Reference

| [1] | Krautkrämer, J., Krautkrämer, H.: Ultrasonic Testing of Materials. Springer, Berlin (1990) 4th Edition, (ISBN 978-3-540-51231-8) |

| [2] | Lerch, R., Sessler, G., Wolf, D.: Technische Akustik – Grundlagen und Anwendung. Springer, Berlin (2009) (ISBN 978-3-540-49833-9) |

| [3] | Möser, M.: Technische Akustik. Springer, Berlin (2015) (ISBN 978-3-662-47704-5) |

| [4] | Matthies, K. u. a.: Dickenmessung mit Ultraschall. DVS Media Publishing, Berlin (1998) 2nd Edition (ISBN 3-87155-940-7; see AMK-Library under M 44) |

| [5] | Deutsch, M.; Platte, V.; Vogt, M.: Ultraschallprüfung. Grundlagen und industrielle Anwendungen. Springer, Berlin (1997) (ISBN 3-540-62072-9; see AMK-Library under M 45) |

| [6] | Busse, G.: Non-destructive Polymer Testing. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser, Munich (2022) 3rd Edition, pp. 431–495 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; E-Book: ISBN 978-1-56990-807-5; see AMK-Library under A 22) |