Bend Loading: Difference between revisions

Oluschinski (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{Language_sel|LANG=ger|ARTIKEL=Biegebeanspruchung}} {{PSM_Infobox}} <span style="font-size:1.2em;font-weight:bold;">Bend loading</span> __FORCETOC__ ==General== Bending loading is one of the most common types of loading encountered in practice and is therefore of great importance for determining the material values of plastics and fibre composites. The load type is used specifically for the following test methods: * Flexural test f..." |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 14:03, 28 November 2025

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Bend loading

General

Bending loading is one of the most common types of loading encountered in practice and is therefore of great importance for determining the material values of plastics and fibre composites. The load type is used specifically for the following test methods:

- Flexural test for characterizing thermoplastic and thermoset moulding compounds and filled and reinforced composites,

- mechanical-thermal bending stress to determine the heat distortion temperature in the HDT test, and

- medial-mechanical bending loading to determine the stress cracking resistance.

Quasi-static bending test

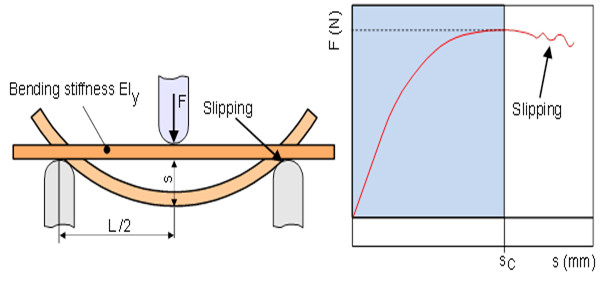

The quasi-static flexural test should be used in particular for testing brittle materials that cause measurement problems in the tensile test due to their failure behaviour. In testing practice, however, this test is also used for ductile plastics that do not break when subjected to bending loading. The test is therefore stopped when a limit state is reached (conventional deflection s = 1.5 h with h = test specimen thickness). This is to avoid the influence of stick-slip on the supports at large deflections (Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1: | Slipping of specimen on the supports at high deflection |

As in the case of tensile or compressive loading, the different deformation components that take effect over time and depending on the load must also be taken into account in the evaluation of the measurement results in the case of bending loading. Depending on the type of plastic, linear-elastic, linear-viscoelastic, nonlinear-viscoelastic and plastic deformation components also occur. The ratio of the deformation components in relation to the total deformation depends on the particular plastic and the loading conditions (temperature and test speed).

Consequently, the material values determined in the bending test are a function of the deformation, the strain rate, the load or stress, the temperature and the internal condition of the test specimen.

Determination of the bending moment curve

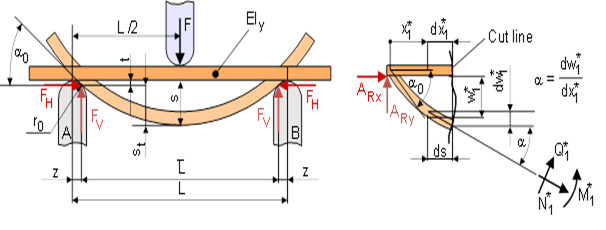

For the evaluation of the bending behaviour and the calculation of the flexural stress as well as the corresponding peripheral fibre strains, the elastic line is used when the bending moment curve (3P or 4P-bending line) is known. The bending line of the deformed specimen is obtained from Eq. (1) and Fig. 2 as follows:

| (1) |

| Fig. 2: | Bend line for 3P-bending on deformed specimen (theory second order) |

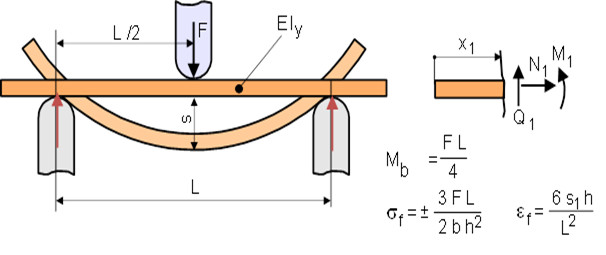

Since this differential equation and the associated boundary conditions depend on the inclination of the elastic line, this equation can only be solved numerically. For a solution that is manageable in engineering terms, it was therefore agreed to use the bending line on the undeformed specimen. Thus, the inclination of the bending line with ds/dx ≈ 0 becomes negligible and the simplified bending line according to Eq. (2) and Fig. 3 is obtained:

| (2) |

| Fig. 3: | Bending line for 3P-bending on undeformed specimen (theory first order) |

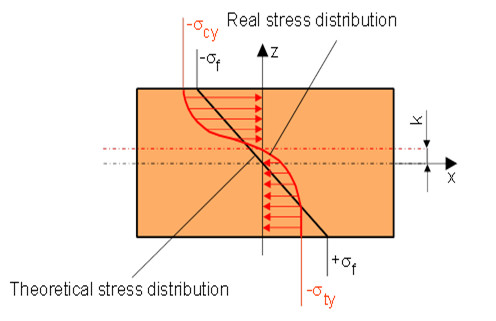

However, the solution of this differential equation with the bending stress σf and the peripheral fibre strain εf is only valid for small deflections (s << h), which is why interpretative problems often arise with ductile plastics in testing practice with deflections of up to 6 mm (s = 1.5 h, h = 4 mm). The application of these evaluation equations also presupposes a symmetrical stress and strain distribution over the cross-section, so that the zero line of the stress or strain is identical to the neutral fibre of the bending beam. As a result of the sometimes very different tensile and compressive behaviour of the plastics (for example polystyrene PS) with differing yield stresses σty and σcy, a shift k of the neutral fibre (Fig. 4) can therefore occur. As a result, the evaluation equations of the bending test are really no longer applicable.

| Fig. 4: | Shifting of neutral fibre at different tension and compression behaviour |

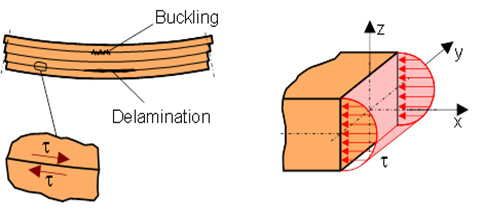

In addition to these normal stresses, parabolically distributed shear stresses occur across the cross-section, especially with thick specimens or very small support spans (Fig. 5). These shear stresses can cause delamination between the layers, especially in the case of laminae on the tensile side, and lead to incorrect material values. For this reason, the span-to-height ratio for isotropic and homogeneous plastics should be L = (16 ± 1) h, and for laminates a ratio of L = (20–25 ± 1) h should be maintained.

| Bild 5: | Influence of shear stress in the cross-section area |

A comprehensive literature analysis on the mechanical properties εf, σfM and σfc under flexural stress is given for numerous plastics in [3].

See also

- Bend test

- Bend test – Test influences

- Bend test – Specimen preparation

- Bend test – Shear stress

- Bend test – Yield stress

- Bend test – Specimen shapes

References

| [1] | Bierögel, C.: Bend Test on Polymers. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S. (Eds.): Polymer Testing. Carl Hanser Munich (2022) 3. Edition, 133–143 (ISBN 978-1-56990-806-8; see under AMK-Library A 22) |

| [2] | Szabó, I.: Einführung in die Technische Mechanik. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg (1984) 8th Edition, (ISBN 3-540-13293-7) |

| [3] | Bierögel, C., Grellmann, W.: Bend Loading. In: Grellmann, W., Seidler, S.: Mechanical and Thermomechanical Properties of Polymers. Landolt-Börnstein. Volume VIII/6A3, Springer Verlag, Berlin (2014) S. 164–191 |

![{\displaystyle {\frac {s^{\prime \prime }(x)}{[1+s^{\prime 2}(x)]^{\frac {3}{2}}}}=-{\frac {M_{b}(x)}{E\ I_{y}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c34c56bc7aa8e81a5dd3f1176add4319341382c9)