Fracture Types: Difference between revisions

Oluschinski (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{Language_sel|LANG=ger|ARTIKEL=Brucharten}} {{PSM_Infobox}} <span style="font-size:1.2em;font-weight:bold;">Fracture types</span> __FORCETOC__ ==Types of fracture== In fracture mechanics, macroscopic examination of fracture surfaces initially distinguishes between normal stress fracture (separating fracture) and shear fracture. Depending on the type of mechanical stress, uniaxial stress is referred to as fast (bri..." |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 09:34, 2 December 2025

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Fracture types

Types of fracture

In fracture mechanics, macroscopic examination of fracture surfaces initially distinguishes between normal stress fracture (separating fracture) and shear fracture. Depending on the type of mechanical stress, uniaxial stress is referred to as fast (brittle) fracture and alternating stress as vibration fracture (see also: fatigue).

Macroscopic fracture features

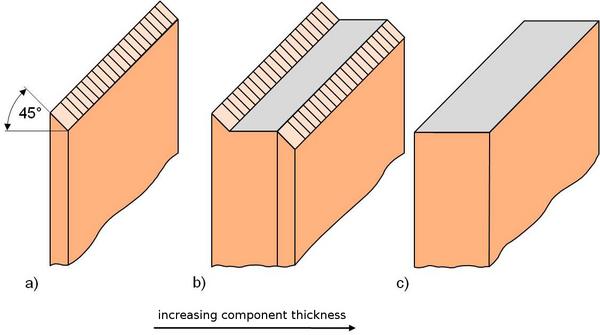

Macroscopic features can be either the extent of the plastic deformation preceding the fracture or the fracture shape (Fig. 1), which depends on the stress state (see uniaxial and multiaxial stress state) and the component thickness [1].

| Fig. 1: | Macroscopic fracture features on plate-shaped components (according to [1]) a) Shear fracture (shear-plane fracture) |

Shear fracture (Fig. 1a) is a consequence of the plane stress state as it occurs approximately in components of constant thickness that is significantly smaller than the other dimensions due to loading in the component plane. Failure is initiated by exceeding critical shear stresses (see example: component failure).

In contrast, a plane strain state can develop in thicker components, leading to separation failure. The separation occurs perpendicular (normal) to the tensile stress. Figure 1b corresponds to a mixed stress state (plane stress state at the edge, plane strain state or triaxial stress state inside the component; see: plane stress and strain state). With increasing component thickness, the tendency toward normal stress fracture (normal-surface separation fracture) increases (Fig. 1c), so that the width of the shear lips occurring at the edge is a measure of the plasticity reserve. The shear lips arise as plastic deformation in the area of the plane stress state as a result of the free deformability at the surface of the component. The size depends on the material but also on the environmental conditions, such as stress temperature and deformation rate. Under constant stress and environmental conditions, the area on the fracture surface in which the plane strain state leads to a low-deformation separation fracture increases with increasing wall thickness. The area in which shear lips form as a result of the plane stress state remains constant.

Microscopic fracture features

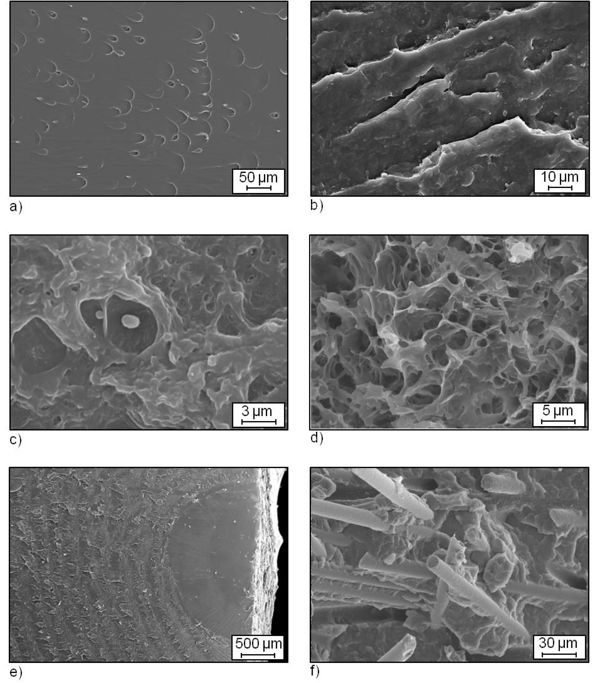

The microscopic fracture characteristics are determined by the fracture mechanism, i.e., the processes involved in crack propagation. In addition to the two basic mechanisms of splitting and shearing, trans- or intercrystalline crack propagation can also be regarded as a fracture feature in crystalline materials. Figure 2 shows the basic types of microscopic fracture features of plastics [1].

| Fig. 2: | Selected microscopic fracture features for plastics

|

Deformation phenomena

Crazing is a micromechanical deformation mechanism that is very commonly observed in plastics.

Crazes are normal stress cracks that contain plastically stretched material parallel to the direction of stress (see tensile test) under tensile stress. The areas under tensile stress are relieved by stretched fibrils. Ehrenstein [2] describes these deformation phenomena as "stabilized" fast (brittle) cracks, whose separation surfaces are bridged by stretched fibrils and fibres with a fibril diameter of 0.01 to 0.1 µm. Crazes can occur both on free surfaces (see also: fracture surface) and inside the test specimen and are therefore semi-circular or circular in shape. In transparent plastics, the extent of the circle can be seen with the naked eye (white fracture) [2].

See also

References

| [1] | Blumenauer, H., Pusch, G.: Technische Bruchmechanik (Technical fracture mechanics). Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig Stuttgart (1982); (see AMK-Library under E 29-1) |

| [2] | Ehrenstein, G. W., Engel, K., Klingele, H., Schaper, H.: Scanning Electron Microscopy of Plastics Failure / REM von Kunststoffschäden. Carl Hanser, Munich (2011), (ISBN 978-3-446-42242-1; see AMK-Library under D 5) |