Microplastic & Nanoplastic

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Microplastic & Nanoplastic (Authors: Prof. Dr. Vasiliki-Maria Archodoulaki und Dr. Lisa Schardt)

Microplastics

General remarks

Microplastics are a technically and ecologically relevant class of polymer particles. They have been the subject of increased research in recent years, after being first described more than 20 years ago [1, 2]. Numerous questions regarding their origin, occurrence and effects remain unanswered and are the subject of current research. The occurrence of microplastics in marine systems is comparatively well documented [3]. However, less is known about terrestrial and atmospheric environmental compartments and consumer goods such as food [4]. The potential effects on humans are also being investigated, but have not yet been adequately quantified [5]. Even less data is available on nanoplastics, a collective term for even smaller plastic particles [6].

Definitions

There is no uniform and universally accepted definition of microplastics or nanoplastics. Most scientific publications use an upper size limit of 5 mm for microplastics. Particles < 100 nm [7] or < 1 µm [6] are often classified as nanoplastics. However, the lower size limit is often determined by the resolution of the analytical method used.

Regulatory definitions:

- ECHA (European Chemicals Agency): Microplastics comprise particles with a maximum size of 0.1 µm to 5 mm in any direction. An additional category includes fibrous particles with a maximum length of > 5 mm to < 15 mm and an aspect ratio > 3 [8].

- EPA (US Environmental Protection Agency): Microplastics are plastic particles with a size of 1 nm to 5 mm that have a negative impact on the environment and human health.

There are other definitions in the literature with different upper limits, e.g. 2 mm [9] or 1 mm [5, 10]. This lack of standardisation makes it difficult to compare study results.

Classification and origin

Microplastics are often divided into primary and secondary microplastics.

- Primary microplastics: Primary microplastics include particles that were originally manufactured on a micro scale. Examples include microbeads in cosmetic products and glitter particles. Many definitions also include particles that enter the environment directly on a micro scale through abrasion or flaking, e.g. tyre abrasion or paint particles. The proportion of primary microplastics in the total marine occurrence is estimated at around 20–30 % [11]. The production of microplastic particles is increasingly restricted by legal regulations, so their proportion should decrease in the future [8, 12].

- Secondary microplastics: Secondary microplastics are created by the fragmentation of larger plastic objects as a result of physical, chemical or biological degradation processes (see: ageing). It is estimated that they account for around 70–80 % of marine microplastics [11]. As their formation is based on uncontrolled degradation processes, regulatory restrictions are only possible indirectly [13]. The main degradation mechanisms include UV radiation, thermal stress, mechanical abrasion and microbially influenced processes, which often take place in biofilms on the particle surface [14].

This classification can also be applied to nanoplastics [6].

Challenges

Both particle classes have the problem that their small size makes detection, identification and quantification difficult [15]. Most analytical techniques are unable to cover the entire size range of nano- and microplastics, which further complicates comprehensive analysis [16]. Another major challenge is avoiding contamination, as microplastics and nanoplastics are ubiquitous in the environment and many laboratory items are made of plastic [17]. In addition, sample preparation and extraction from complex matrices such as sediments, biological tissue or food require complex protocols that often still need to be developed [18]. The resulting measurements therefore show high variability. Concentration data and exposure estimates should be interpreted with caution, especially in complex systems.

Sources and released quantities

Reliable estimates of the sources and release quantities of microplastics are difficult to obtain, as secondary microplastics account for a large proportion of microplastics in the environment. Various studies have attempted to estimate the sources and quantities of microplastics produced (Fig. 1) [19–21]. The reported values vary depending on the ecosystems and regions considered. Overall, tyre abrasion and textile fibres are considered to be the most significant sources of microplastics in the environment [22]. The global amount released is estimated at 3.0–5.3 million tonnes per year [22].

| Fig. 1: | The main sources of primary and secondary microplastics in the sea |

Microplastics as pollutants

Microplastics are considered to be potentially harmful to the environment and human health. Their toxicity depends on many factors, such as particle size, shape, material, additives contained, and pollutants adsorbed on the surface. The groups of substances that are frequently adsorbed include metals, endocrine-disrupting substances and persistent organic pollutants [23, 24]. In addition, microplastics can act as carriers for pathogens and microorganisms that form biofilms on the particle surface [25].

Occurrence in the environment

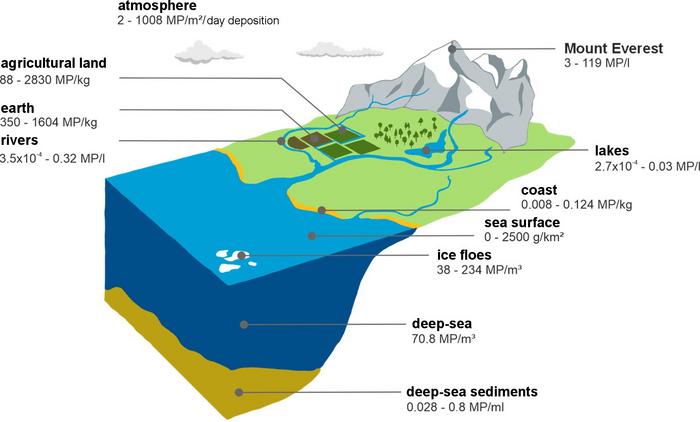

Microplastics have been detected in all areas of our environment, including freshwater, soil, air and oceans, as well as in remote regions such as the Arctic and Alpine areas (Fig. 2) [14]. Research initially focused primarily on marine systems, particularly surface waters and coastal zones. Other environmental areas such as soil, sediments and the atmosphere have been studied much less extensively in comparison.

Microplastics enter water bodies through direct inputs such as sewage or through transport from other areas such as precipitation. In water bodies, depending on their density and flow conditions, microplastics can float in the water column, accumulate on the surface or be deposited in sediments [3]. As long as no deposition occurs, microplastics are transported in the water cycle and thus enter coastal regions and oceans from rivers [22].

Microplastics enter the soil from sewage sludge, tyre abrasion, mulch films and deposition from the atmosphere [26]. As there is only a small amount of transport of microplastics from the soil to other areas, microplastics can often accumulate here and reach higher concentrations than in the marine environment, for example. Microplastics have been detected in the atmosphere in both urban and rural regions. Atmospheric transport by wind contributes significantly to the long-range distribution of particles and also transports them to remote areas such as high mountains and polar regions [27].

Plants can absorb microplastics through their roots [28]. The consequences include altered root growth, changes in metabolism and reduced nutrient uptake. Another effect of microplastics is disruption of the soil structure, which reduces water retention capacity and leads to a decrease in crop yields [29, 30].

Animals, like humans, absorb microplastics primarily orally and through inhalation. While acute toxicity is rarely observed, chronic effects often occur, such as:

- Bioaccumulation in the digestive tract and tissue

- Inflammatory reactions and oxidative stress

- Impaired food intake or locomotion

- Changes in metabolism

- Changes in reproduction [31].

The observed consequences depend on particle properties such as size, shape and material, but also on the duration and concentration of exposure. Due to its smaller size, nanoplastics can more easily overcome biological barriers and increasingly enter cells and tissue [7].

| Fig. 2: | Number of microplastic particles (MP) in different areas of the environment (based on Thompson et al., Science 2024) |

Influence on human health

Humans can absorb microplastics through oral ingestion, inhalation and, to a much lesser extent, through the skin.

- Oral intake:

- Estimates of the annual number of particles ingested orally vary widely, ranging from approximately 11,000 [32] to 113,000 [33, 34] particles per person. These values should be considered rough approximations, as standardised analytical methods are lacking for many food groups and reliable sample data is often unavailable. Microplastics have been detected in various foods, including drinking water, salt, honey and fish [35]. Food packaging can also be an additional source, for example tea bags or disposable containers [36, 37]. Regional differences in diet and hygiene standards also influence exposure [38]. Despite this uncertainty in determination, it can be assumed that relevant amounts of microplastics enter the human body via food.

- Inhalation:

- The sources of this include textile fibres, house dust, tyre abrasion and industrial emissions [39]. One study estimates the annual inhalation intake indoors to be around 65,000–80,000 particles [40]. Particles < 10 µm can enter the lower respiratory tract, and particles < 1 µm can penetrate the alveoli and possibly enter the bloodstream [41]. Inhaled microplastics can trigger local inflammatory reactions in the lungs, which can lead to chronic diseases such as asthma, COPD and cancer [41].

- Dermal absorption:

- plays a minor role. There is evidence that particles < 100 nm can penetrate the skin barrier under certain conditions, especially in pre-damaged skin [42]. Quantitative data on dermal exposure are currently scarce.

Microplastics have been detected in various human tissues, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, placenta and faecal samples (Fig. 3) [43]. This suggests that some of the particles ingested are excreted, while others remain in the body or are transported to organs [43, 44]. There is currently little knowledge about the long-term health effects of microplastics [45]. Particles < 1.5 µm can penetrate tissue and cause damage within cells [46], while particles < 10 µm can cross the placental barrier [47]. Irregularly shaped, sharp-edged or fibrous particles have an increased potential for mechanical tissue damage due to their geometry and often remain in the organism for longer before being excreted [48].

| Fig. 3: | Schematic overview of the oral intake, distribution and excretion of microplastics in the human body |

In addition to mechanical effects, polymer-bound additives such as phthalates or bisphenol A, as well as substances adsorbed on the surface, including heavy metals and organic contaminants, can be released into the organism and influence biological processes [49]. If microplastic particles enter tissue, they can trigger oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions, which have been linked in the literature to various immunological and chronic diseases [31]. In cell culture studies, cytotoxic effects have been described at concentrations of around 10 µg/mL; immunological reactions occurred at concentrations of around 20 µg/mL [50].

Table 1: Summary of the properties of microplastics that are relevant to toxicity and their health consequences (modified from Koelmans et al. Nature 2022)

| particle type | relevant properties | possible consequences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microparticles (1–1000 μm) | ||||

| organic material | chemical composition, digestibility | chemical toxicity | ||

| microplastic | size, volume, surface area, aspect ratio, shape, adsorbed chemicals | chemical toxicity | thinning of food, mechanical irritation, inflammation, oxidative stress | |

| coal | size, surface area, chemical composition | pneumoconiosis, fibrosis, cancer | ||

| Particles that occur in micrometre and nanometre sizes | ||||

| asbestos | fibre length, aspect ratio, type, persistence | asbestosis, pleural disease, lung cancer, mesothelioma | translocation, biodistribution, mechanical irritation, oxidative stress | |

| desert dust aerosols | size, surface, shape | breathing difficulties, silicosis | ||

| quartz (silica) | size, surface, shape | release of silica, cancer | ||

| Nanoparticle (1–1,000 nm) | ||||

| carbon black | size, surface, adsorb chemicals | respiratory and cardiovascular disease, cancer | ||

| nanoplastic | size, surface area, charge, length, size ratio, aggregation, sorbed chemicals | unknown | ||

| carbon-nanotubes | size, surface, length, aspect ratio, aggregation, sorbed chemicals | fibrosis, infections, cancer | ||

| metal based nano materials | size, surface, charge, zeta potential, solubility, aggregation | inflammation, mitochondrial damage, DNA damage | ||

| colloids made from organic material | digestibility, sorbed chemicals | chemical toxicity | ||

Properties of microplastic particles

Shape

Microplastic particles can occur in various forms, such as fragments, fibres, films, pellets and foams [51]. Primary microplastics are usually spherical, while secondary microplastics are mostly irregular in shape [52]. The shape is determined by the originally produced plastic product and the ageing and degradation processes to which it is subjected. The shape can therefore be used to narrow down the source of microplastics found. Round particles typically originate from cosmetic products or industrial applications, while fibres are often released from textiles [53, 54].

The particle shape influences the toxicological potential. Elongated particles and sharp-edged fragments can cause more severe physical damage than round particles [50, 55, 56]. Fibres often remain in organisms for longer and therefore have an increased potential for damage [57]. It follows that secondary microplastics are generally more harmful than primary microplastics due to their typical shapes [55].

Material

The most commonly identified materials in microplastics are polyethylene (abbreviation: PE), polypropylene (abbreviation: PP), polystyrene (abbreviation: PS), polyvinyl chloride (abbreviation: PVC), polyethylene terephthalate (abbreviation: PET) and rubber from tyre abrasion (Fig. 2). These are the plastics most commonly used in the manufacture of consumer products [58]. Transport in the environment depends heavily on polymer density; polymers with a density < 1 g/cm³ float on the surface and are transported over long distances in water, while particles with a higher density accumulate in the sediment [59].

Compared to size and shape, the material has less influence on toxicity. However, surface charge and hydrophobicity influence the adsorption behaviour towards organic and inorganic contaminants [60]. In addition, most plastics contain additives that are specific to the material and can increase toxicity through leaching [23].

Ageing and degradation processes such as photo-oxidation, hydrolysis or the formation of biofilms alter the surface chemistry and roughness of microplastic particles [14]. This results in oxidised, roughened surfaces with increased reactivity and adsorption capacity, as well as enhanced interaction with biological material.

| Fig. 4: | Plastic types and their presence in microplastics from the environment |

Size

The size of microplastic particles influences their mobility and bioavailability in the environment. The smaller a particle is, the easier it is for it to enter various ecosystems, become part of the food chain or penetrate biological membranes [61]. Smaller particles also remain in some organisms for longer before being excreted [48]. The specific surface area has a significant influence on the adsorption of pollutants and the release of polymer additives [62]. Smaller particles often remain in suspension for longer and can therefore be transported over greater distances [63].

Microplastics and nanoplastics occur in a wide range of sizes, the distribution of which is determined by the respective source and the degradation processes they have undergone. Primary microplastics usually have a more narrow size distribution than secondary microplastics and nanoplastics. Particle sizes of 6–100 µm have been detected in bottled drinking water, while particles up to about 1 mm have been observed in foods such as fish, salt or poultry tissue [35]. All sizes up to the limit of 5 mm occur in the environment.

Acknowledgement

The editors of the encyclopaedia would like to thank Prof. Dr. Vasiliki-Maria Archodoulaki and Dr. Lisa Schardt, Vienna University of Technology, Institute for Materials Science and Technology, Structural Polymers Research Group, for this guest contribution

See also

- Plastics

- Barrier plastics

- Smart materials

- Bio-Plastics

- Layer silicate-reinforced polymers

- Particle-filled thermoplastics

- Short-fibre reinforced plastics

- Fibre-reinforced plastics

- Polymer blend

References

| [1] | Thompson, R. C., Courtene-Jones, W., Boucher, J., Pahl, S., Raubenheimer, K.; Koelmans, A. A.:Twenty years of microplastic pollution research – what have we learned? Science 386 (6720), eadl2746. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adl2746 |

| [2] | Thompson, R. C., Olsen, Y., Mitchell, R. P., Davis, A., Rowland, S. J., John, A. W. G., McGonigle, D., Russell, A. E.: Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic? Science 2004, 304 (5672), 838-838. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1094559 |

| [3] | Ivar do Sul, J. A., Costa, M. F.: The present and future of microplastic pollution in the marine environment. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 185, 352–364. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2013.10.036 |

| [4] | Akdogan, Z., Guven, B.: Microplastics in the environment: A critical review of current understanding and identification of future research needs. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113011 |

| [5] | Browne, M. A., Galloway, T. S., Thompson, R. C.: Spatial Patterns of Plastic Debris along Estuarine Shorelines. Environmental Science & Technology 2010, 44 (9), 3404-3409. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/es903784e |

| [6] | Napper, I. E., Thompson, R. C.: Plastic Debris in the Marine Environment: History and Future Challenges. Global Challenges 2020, 4 (6), 1900081. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.201900081 (acccessed 2025/10/10) |

| [7] | Masseroni, A., Rizzi, C., Urani, C., Villa, S.: Nanoplastics: Status and Knowledge Gaps in the Finalization of Environmental Risk Assessments. In Toxics, 2022; Vol. 10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics10050270 |

| [8] | Commission, E.: Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/2055. In 2023/2055, Commission, E., Ed.; Official Journal of the European Union, 2023; Vol. 2023/2055, pp 238/267–238/288 |

| [9] | Ryan, P. G., Moore, C. J., van Franeker, J. A., Moloney, C. L.: Monitoring the abundance of plastic debris in the marine environment. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2009, 364 (1526), 1999–2012; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0207; From NLM |

| [10] | Galloway, T. S.: Micro- and Nano-plastics and Human Health. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter, Bergmann, M., Gutow, L., Klages, M. Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2015; pp 343–366 |

| [11] | Boucher, J., Friot, D.: Primary microplastics in the oceans : a global evaluation of sources; IUCN, Global Marine and Polar Programme, 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2017.01.en |

| [12] | Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015. In H. R.1321 2015 |

| [13] | Yousafzai, S., Farid, M., Zubair, M., Naeem, N., Zafar, W., Zaman Asam, Z. ul., Farid, S., Ali, S.: Detection and degradation of microplastics in the environment: a review. Environmental Science: Advances 2025, 4 (8), 1142–1165, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/D5VA00064E |

| [14] | Andrady, A. L.: The plastic in microplastics: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119 (1), 12-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.01.082 |

| [15] | Adhikari, S., Kelkar, V., Kumar, R., Halden, R. U.: Methods and challenges in the detection of microplastics and nanoplastics: a mini-review. Polymer International 2022, 71 (5), 543–551. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.6348 (acccessed 2025/10/10) |

| [16] | Choi, S., Lee, S., Kim, M.-K., Yu, E.-S., Ryu, Y.-S.: Challenges and Recent Analytical Advances in Micro/Nanoplastic Detection. Analytical Chemistry 2024, 96 (22), 8846-8854. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.3c05948 |

| [17] | Bogdanowicz, A., Zubrowska-Sudol, M., Krasinski, A., Sudol, M.: Cross-Contamination as a Problem in Collection and Analysis of Environmental Samples Containing Microplastics – A Review. In Sustainability, 2021; Vol. 13 |

| [18] | Zhang, H.; Duan, Q.; Yan, P.; Lee, J.; Wu, W.; Zhou, C.; Zhai, B.; Yang, X. Advancements and challenges in microplastic detection and risk assessment: Integrating AI and standardized methods. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 212, 117529. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.117529 |

| [19] | Kovochich, M., Liong, M., Parker, J., Su Cheun, O., Jessica, P. L., Xi, L., Kreider, M., Unice, K.: Chemical mapping of tire and road wear particles for single particle analysis. The Science of the total environment 2020, 757, 144085. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144085 |

| [20] | Unsbo, H., Rosengren, H., Olshammar, M.: Indicators for microplastic flows; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 2022. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1730362/FULLTEXT01.pdf |

| [21] | Verschoor, A., René van Herwijnen, Connie Posthuma, Klesse, K., Werner, S.: Assessment document of land-based inputs of microplastics in the marine environment; OSPAR, 2017. https://www.ospar.org/documents?v=38018 |

| [22] | Ryberg, M., Laurent, A., Hauschild, M. Z.: Mapping of global plastic value chain and plastic losses to the environment: with a particular focus on marine environment; United Nations Environment Programme, 2018 |

| [23] | Paul, M. B., Stock, V., Cara-Carmona, J., Lisicki, E., Shopova, S., Fessard, V., Braeuning, A., Sieg, H., Böhmert, L.: Micro- and nanoplastics – current state of knowledge with the focus on oral uptake and toxicity. Nanoscale Advances 2020, 2 (10), 4350-4367, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/D0NA00539H |

| [24] | Baudrimont, M., Arini, A., Guégan, C., Venel, Z., Gigault, J. Pedrono, B., Prunier, J., Maurice, L., Ter Halle, A., Feurtet-Mazel, A.: Ecotoxicity of polyethylene nanoplastics from the North Atlantic oceanic gyre on freshwater and marine organisms (microalgae and filter-feeding bivalves). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27 (4), 3746-3755. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04668-3 |

| [25] | Hong, J.-K., Oh, H., Lee, T. K., Kim, S., Oh, D., Ahn, J., Park, S.: Tracking the Evolution of Microbial Communities on Microplastics through a Wastewater Treatment Process: Insight into the “Plastisphere”. Water 2023, 15 (21), 3746 |

| [26] | Guo, J., Huang, X., XIang, L., Wang, Y., Li, Y., Li, H., Cai, Q., Mo, C. Wong, M.: Source, migration and toxicology of microplastics in soil Environment International 2020 137, 105263 |

| [27] | Munyanezy, J., Jia, Q., Qaraah, F., Hossain, M., Wu, C., Zhen, H., Xiu, G.: A review of atmospheric microplastic pollution: In-depth sighting of sources, analytical methods, physiognomies, transport and risks Science of the Total Environment 2022 822, 153339 |

| [28] | Du, H., Peng, C., Li, Y., Shi, X., Liu, C., Liu, W. Wang, L. Absorption of microplastics by terrestrial plants and their ecological risk. New Contaminants 2025, 1 (1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.48130/newcontam-0025-0006 |

| [29] | de Souza Machado, A. A., Lau, C. W., Kloas, W., Bergmann, J., Bachelier, J. B., Faltin, E., Becker, R., Görlich, A. S., Rillig, M. C.: Microplastics Can Change Soil Properties and Affect Plant Performance. Environmental Science & Technology 2019, 53 (10), 6044-6052. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b01339 |

| [30] | Bosker, T., Bouwman, L. J., Brun, N. R., Behrens, P., Vijver, M. G.: Microplastics accumulate on pores in seed capsule and delay germination and root growth of the terrestrial vascular plant Lepidium sativum. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 774–781. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.163 |

| [31] | Pelegrini, K., Pereira, T. C. B., Maraschin, T. G., Teodoro, L. D. S., Basso, N. R. D. S., De Galland, G. L. B., Ligabue, R. A., Bogo, M. R.: Micro- and nanoplastic toxicity: A review on size, type, source, and test-organism implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 162954. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162954 |

| [32] | Van Cauwenberghe, L., Janssen, C. R.: Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 193, 65–70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2014.06.010 |

| [33] | Cox, K. D., Covernton, G. A., Davies, H. L., Dower, J. F., Juanes, F., Dudas, S. E.: Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environmental Science & Technology 2019, 53 (12), 7068-7074. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b01517 |

| [34] | Cox, K. D., Covernton, G. A., Davies, H. L., Dower, J. F., Juanes, F., Dudas, S. E.: Correction to Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environmental Science & Technology 2020, 54 (17), 10974-10974. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c04032 |

| [35] | Bai, C.-L., Liu, L.-Y., Hu, Y.-B., Zeng, E. Y., Guo, Y.: Microplastics: A review of analytical methods, occurrence and characteristics in food, and potential toxicities to biota. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150263. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150263 |

| [36] | Velickova Nikova, E., Temkov, M., Rocha, J. M.: Chapter Two - Occurrence of meso/micro/nano plastics and plastic additives in food from food packaging. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, Özogul, F. Ed.; Vol. 103; Academic Press, 2023; pp 41–99 |

| [37] | Shruti, V. C., Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.: Migration testing of microplastics in plastic food-contact materials: Release, characterization, pollution level, and influencing factors. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 170, 117421. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2023.117421 |

| [38] | Garrido Gamarro, E., Costanzo, V.: Microplastics in food commodities – A food safety review on human exposure through dietary sources. Food Safety and Quality Series, FAO, 2022 |

| [39] | Santizo, K. Y., Mangold, H. S., Mirzaei, Z., Park, H. Kolan, R. R., Sarau, G., Kolle, S., Hansen, T., Christiansen, S., Wohlleben, W.: Microplastic Materials for Inhalation Studies: Preparation by Solvent Precipitation and Comprehensive Characterization. Small 2025, 21 (7), 2405555. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202405555 |

| [40] | Ageel, H. K., Harrad, S., Abdallah, M. A.-E.: Microplastics in indoor air from Birmingham, UK: Implications for inhalation exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 362, 124960. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124960 |

| [41] | Abad López, A. P., Trilleras, J., Arana, V. A., Garcia-Alzate, L. S., Grande-Tovar, C. D.: Atmospheric microplastics: exposure, toxicity, and detrimental health effects. RSC Adv 2023, 13 (11), 7468-7489, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/D2RA07098G |

| [42] | Sykes, E. A., Dai, Q., Tsoi, K. M., Hwang, D. M., Chan, W. C. W.: Nanoparticle exposure in animals can be visualized in the skin and analysed via skin biopsy. Nature Communications 2014, 5 (1), 3796. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4796 |

| [43] | Roslan, N. S.; Lee, Y. Y.; Ibrahim, Y. S.; Tuan Anuar, S.; Yusof, K.; Lai, L. A.; Brentnall, T. Detection of microplastics in human tissues and organs: A scoping review. J Glob Health 2024, 14, 04179. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.14.04179 |

| [44] | Dzierżyński, E., Blicharz-Grabias, E., Komaniecka, I. Panek, R., Forma, A., Gawlik, P. J., Puźniak, D., Flieger, W., Choma, A., Suśniak, K., et al.: Post-mortem evidence of microplastic bioaccumulation in human organs: insights from advanced imaging and spectroscopic analysis. Archives of Toxicology 2025, 99 (10), 4051–4066. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-025-04092-2 |

| [45] | Li, Y., Tao, L., Wang, Q., Wang, F., Li, G., Song, M.: Potential Health Impact of Microplastics: A Review of Environmental Distribution, Human Exposure, and Toxic Effects. Environment & Health 2023, 1 (4), 249–257. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/envhealth.3c00052 |

| [46] | Hussain, N., Jaitley, V., Florence, A. T.: Recent advances in the understanding of uptake of microparticulates across the gastrointestinal lymphatics. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2001, 50 (1), 107-142. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00152-1 |

| [47] | Braun, T., Ehrlich, L., Henrich, W., Koeppel, S. Lomako, I. Schwabl, P. Liebmann, B.: Detection of Microplastic in Human Placenta and Meconium in a Clinical Setting. In Pharmaceutics, 2021; Vol. 13 |

| [48] | Park, J.-S., Yoo, J.-W., Lee, Y.-H., Park, C., Lee, Y.-M.: Size- and shape-dependent ingestion and acute toxicity of fragmented and spherical microplastics in the absence and presence of prey on two marine zooplankton. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 206, 116768. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116768 |

| [49] | Li, M., Ma, W., Fang, J. K. H., Mo, J., Li, L., Pan, M., Li, R., Zeng, X. Lai, K. P.: A review on the combined toxicological effects of microplastics and their attached pollutants. Emerging Contaminants 2025, 11 (2), 100486. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emcon.2025.100486 |

| [50] | Danopoulos, E., Twiddy, M., West, R., Rotchell, J. M.: A rapid review and meta-regression analyses of the toxicological impacts of microplastic exposure in human cells. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 127861. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127861 |

| [51] | Anderson, P. J., Warrack, S., Langen, V., Challis, J. K., Hanson, M. L., Rennie, M. D.: Microplastic contamination in Lake Winnipeg, Canada. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 225, 223–231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.072 |

| [52] | Bom, F. C., Sá, F.: Concentration of microplastics in bivalves of the environment: a systematic review. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2021, 193 (12), 846. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-021-09639-1 |

| [53] | Not, C., Chan, K., So, M. W. K., Lau, W., Tang, L. T.-W., Cheung, C. K. H.: State of microbeads in facial scrubs: persistence and the need for broader regulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32 (17), 11063–11071. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-025-36341-3 |

| [54] | Microplastics from textiles: towards a circular economy for textiles in Europe; European Environment Agency, Briefing no. 16/2021, 2021. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2800/863646 |

| [55] | Xia, B., Sui, Q., Du, Y., Wang, L., Jing, J., Zhu, L., Zhao, X., Sun, X. Booth, A. M., Chen, B., et al.: Secondary PVC microplastics are more toxic than primary PVC microplastics to Oryzias melastigma embryos. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127421. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127421 |

| [56] | Choi, D., Hwang, J., Bang, J., Han, S. Kim, T., Oh, Y. Hwang, Y., Choi, J. Hong, J.: In vitro toxicity from a physical perspective of polyethylene microplastics based on statistical curvature change analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 142242. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142242 |

| [57] | Renzi, M., Guerranti, C., Blašković, A.: Microplastic contents from maricultured and natural mussels. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 131, 248-251. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.04.035 |

| [58] | Tursi, A., Baratta, M., Easton, T., Chatzisymeon, E., Chidichimo, F., De Biase, M., De Filpo, G.: Microplastics in aquatic systems, a comprehensive review: origination, accumulation, impact, and removal technologies. In RSC Adv, 2022; Vol. 12, pp. 28318–28340 |

| [59] | He, B., Smith, M., Egodawatta, P., Ayoko, G. A., Rintoul, L., Goonetilleke, A.: Dispersal and transport of microplastics in river sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 279, 116884. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116884 |

| [60] | Tseng, L. Y., You, C., Vu, C., Chistolini, M. K., Wang, C. Y., Mast, K., Luo, F., Asvapathanagul, P., Gedalanga, P. B., Eusebi, A. L., et al.: Adsorption of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) with Varying Hydrophobicity on Macro- and Microplastic Polyvinyl Chloride, Polyethylene, and Polystyrene: Kinetics and Potential Mechanisms. Water 2022, 14 (16), 2581 |

| [61] | Yee, M. S., Hii, L.-W., Looi, C. K., Lim, W.-M., Wong, S.-F., Kok, Y.-Y. Tan, B.-K., Wong, C.-Y., Leong, C.-O.:, Impact of Microplastics and Nanoplastics on Human Health. In Nanomaterials, 2021; Vol. 11 |

| [62] | Costa, J. P. d., Avellan, A., Mouneyrac, C., Duarte, A., Rocha-Santos, T.: Plastic additives and microplastics as emerging contaminants: Mechanisms and analytical assessment. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023, 158, 116898. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2022.116898 |

| [63] | Peries, S. D., Sewwandi, M., Sandanayake, S., Kwon, H.-H., Vithanage, M.: Airborne transboundary microplastics – A Swirl around the globe. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 353, 124080. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124080 |