Environmental-SEM (ESEM)

| A service provided by |

|---|

|

| Polymer Service GmbH Merseburg |

| Tel.: +49 3461 30889-50 E-Mail: info@psm-merseburg.de Web: https://www.psm-merseburg.de |

| Our further education offers: https://www.psm-merseburg.de/weiterbildung |

| PSM on Wikipedia: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymer Service Merseburg |

Environmental-SEM (ESEM) (Author: Dr. Armin Zankel)

General information

The method described here has different names in both German-language and English-language literature, which is partly due to different manufacturers. The characteristic feature of this scanning electron microscope method (SEM) (Fig. 1) is the significantly lower vacuum (higher pressure) in the microscope chamber compared to a conventional scanning electron microscope (10-4–10-7 Torr).

| Fig. 1: | ESEM Quanta 200 from FEI at the Institute for Electron Microscopy and Nanoanalysis at Graz University of Technology, 2003; a: electron column, b: sample chamber, c: EDX detector with nitrogen dewar |

Typically, two working ranges (pressure ranges) can be achieved using a differential pump system:

Low vacuum mode (imaging non-conductive specimens without preparation)

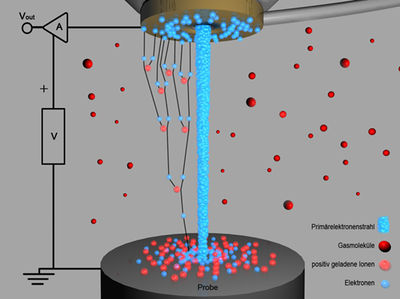

A pressure between approximately 0.1 and 1.5 Torr (1 Torr ≈ 133 Pa) is achieved in the sample chamber. Here, the vacuum is still sufficient to ensure a large portion of non-scattered primary electrons. The purpose of this “poorer” vacuum is to neutralize potential charges on the sample surface caused by the primary electrons. Figure 2 shows a schematic representation of this principle. The primary electrons reach the sample surface. Secondary electrons emitted from the surface are accelerated toward the detector. On their way there, they have the opportunity to ionize gas molecules. This has a twofold advantage: first, the number of electrons reaching the detector increases exponentially (signal amplification), and second, the resulting positive ions serve to neutralize any negative charges that may occur on the sample surface.

| Fig. 2: | Image formation in ESEM. The negatively charged electrons are multiplied in an avalanche (movement toward the detector). Positive ions (movement toward the sample surface) neutralize potential charges on the sample surface. |

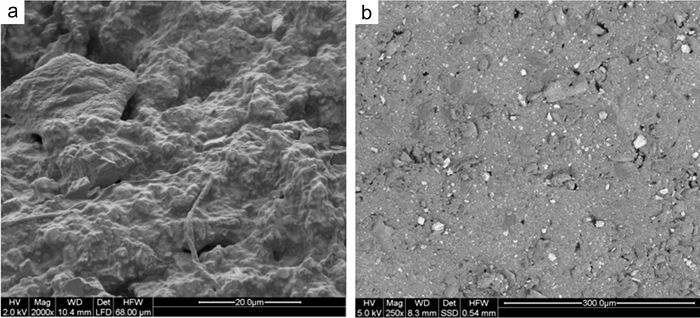

The “Low Vacuum” mode enables the imaging of electrically non-conductive materials (e.g., polymers) using secondary electrons (SE) and backscattered electrons ( RE), e.g., for morphological characterization (Fig. 3). Furthermore, this mode is essential for dynamic investigations of such materials (see in-situ peel test, in-situ tensile test in ESEM with SEA, in-situ ultramicrotomy).

| Fig. 3: | Surface characterization of rubber. a) SE image (topography contrast) b) RE image (material contrast) |

ESEM mode (imaging wet specimens)

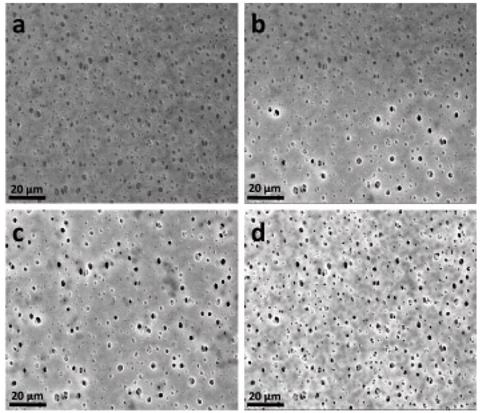

A pressure between approximately 4.5 and 10 Torr (1 Torr ≈ 133 Pa) is achieved in the sample chamber. By simultaneously cooling (e.g., using a Peltier cooling table) a sample to be examined, it is possible to either generate moisture (condensation experiments) or even examine moist samples. Fig. 4 shows the sample surface of a polyether sulfone membrane, which can be used to study moisture behaviour. In ESEM mode, heating tests up to approx. 1500 °C can also be carried out, but these will not be discussed further here.

| Fig. 4: | Series of ESEM images for in situ characterization of the drying process of a polyether sulfone membrane. a) wet membrane, b) start of drying, c) drying of the large pores, d) end of the drying process (ESEM Quanta 600 FEG, pressure: 5.5–6.5 Torr, electron energy 20 keV. |

Chemical analyses can be performed using EDX in both low vacuum mode and ESEM mode, whereby special corrections must be applied during evaluation due to the imaging gas.

Acknowledgements

The editors of the lexicon would like to thank Dr. A. Zankel, Institute for Electron Microscopy and Nanoanalysis (FELMI) and Center for Electron Microscopy (ZFE) Graz for his guest contribution.

See also

- Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX)

- In-situ ultramicrotomy

- Microtomy

- Scanning electron microscopy

- Electron microscopy

References

| [1] | Goldstein, J., Newbury, D., Joy, D., Lyman, Ch., Echlin, P., Lifshin, E., Sawyer, L., Michael, J.: Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis. Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers (2003) (ISBN 0-306-47292-9) |

| [2] | Reimer, L.: Scanning Electron Microscopy. 2nd Edition, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg (1998) (ISBN 3-540-63976-4) |

| [3] | Michler, G. H.: Electron Microscopy of Polymers. Springer, Berlin (2008) (ISBN 978-3-540-36350-7; see AMK-Library under F 1) |

| [4] | Michler, G. H., Lebek, W.: Ultramikrotomie in der Materialforschung. Carl Hanser, Munich Vienna (2004) (ISBN 3-446-22721-0; see AMK-Library under F 5) |

| [5] | Stokes, D.: Principles and Practice of Variable Pressure/Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy (VP-ESEM). Wiley (2008) (http://192.168.81.5/wiki/index.php/Spezial:ISBN-Suche/9780470065402 ISBN 978-0-470-06540-2]) |

| [6] | Reingruber, H., Zankel, A., Pölt, P.: Filtration Membranes, Water and the ESEM. Imaging & Microscopy, GIT-Verlag (2011) 3, pp. 18–21 |

| [7] | Nachtnebel, M., Fitzek, H., Mayrhofer, C., Chernev, B., Pölt, P.: Spatial Localization of Membrane Degradation by in situ Wetting and Drying of Membranes in the Scanning Electron Microscope. Journal of Membrane Science 503 (2016) 81–89 (Link) (access on 23.10.2025) |